It may be hard to believe, but SRAM hasn’t always been the industry juggernaut they are today. Like many bicycle companies before them, SRAM started with an idea. It was an idea for a product that at the time seemed so crazy that it took an outsider to the industry to think it up. After working his way up through the fledgling personal computer industry, the gears had started turning for Stan Day Jr.

In 1986 Stan had an idea for a new type of shifter after being frustrated by the need to reach to the downtube on his bike while training for a triathlon. After leaving his job to work with his father for another job that didn’t end up panning out, Stan met engineer and designer Sam Harwell Patterson on a ski trip in 1987. The two discussed his idea for a shifter, and Sam thought he could make it work. Just a few months later Sam had developed a functional prototype that was a rotating barrel that mounted to a special handlebar – the first GripShift.

Near the end of 1987 the “original six” decided to launch their new shifter at the next big trade show in 1988. Sam would be the head of engineering, Scott King the director of finance and administration, Jeff Shupe would be the head of manufacturing, Michael D. Mercuri the head of OE sales, Stan’s brother Frederick King Day or F.K. joined Stan in managing operations. The team headed to the trade show with a product, but without a company name. After a number of rejected possibilities, SRAM was chosen based on the S from Scott King, R from Stan’s middle name Ray, and AM from Sam Patterson.

While the original GripShift opened the door for the company to try and take even a little market share from the gigantic Shimano, the original design left customers wanting more. So Sam went back to work which led to the adoption of a shovel cam instead of the original helical cam. The design allowed for a much smaller shifter that functioned better and was able to be dialed in for shifting index feel. Called the SRT-100, the shifter would lead to their big break as it was finally picked up as original equipment.

Originally planning to manufacture the shifters in Chicago, a visit to Taiwan where the bikes were to be produced resulted in a change of plans. As we experienced for ourselves, Taiwan is very close knit in their manufacturing and it results in very short lead times. So, on the very same trip Stan set off on establishing a factory in Taiwan. Eventually, they were able to lease a tiny building for SRAM to build their shifters. Little more than a guard hut, the space served its purpose as SRAM was simultaneously building shifters back in Chicago for bikes that were made in the U.S. and the aftermarket.

Having established themselves in Taiwan, the rest of the story is probably more widely known. In 1994, SRAM took a stab at their first product other than a shifter, the ESP 900 plastic derailleur. After a rocky start, SRAM went on to find derailleur success with their X0 product line after acquiring Sachs’ bicycle division in 1997. The first of many acquisitions, SRAM continued with the purchase of Rockshox in 2002, Avid and then Truvativ in 2004, Zipp in 2007, and finally Quarq in 2011.

That may be a long back story, but it’s important to paint a picture of SRAM’s manufacturing today. Truly a global company, SRAM currently has around 3,000 employees in 18-20 locations around the world with the Headquarters still in Chicago and most of the manufacturing (except chains which are made in Portugal) carried out in Taiwan and China. Focusing mostly on SRAM and RockShox’ high end product, their largest Taiwanese facility is the 42,000 m² factory in the Shen Kang district, just outside Taichung. As the first full sized SRAM factory, the facility was built in 1989 and began life as a giant warehouse. Now a sprawling development of different buildings, the Shen Kang factory even has a new clean room for assembling high precision parts like the RockShox Reverb seat post.

As birthplace to many of our favorite SRAM and RockShox products like XX1 and the Pike, there is a lot to see after the break…

Underneath that massive awning above is where all of the delivery trucks drop off all of the parts from their various suppliers. After delivery they are sorted, checked for quality, and then distributed throughout the factory to the assembly areas.

As soon as you step inside the first building you start to get a feel for the scale of the production at Shen Kang. Each worker was constantly turning out parts and considering this is their high end, read lower production, facility, the high production areas must be insanely busy. In no particular order other than the way we were taken through the factory we’ll start at the suspension fork line that at the time was pumping out new Pikes.

A few employees were following step by step illustrated instructions in front of their work station. Like most of the factories we visited, stringent quality control checks along the way help to weed out any issues. As the Pikes glide down the assembly line they are assembled one component at a time by different work stations.

Much of the work is done by hand, though quite a few sophisticated machines are used for specialized tasks. As SRAM’s VP of Marketing David Zimberoff pointed out, “it’s one thing to make and design bike parts, it’s another thing to make and design the machine that makes the parts. Everything you see here, machines, stations, had to be designed by someone at SRAM.” Clearly they’re understandably proud of their ability to create their own machinery in house to automate processes that would be too difficult or costly otherwise. Since you can’t just go out and buy a machine that assembles the compression assembly for a suspension fork, SRAM’s own engineers have to figure out a way to make it work much like Stan and F.K. had to engineer their own processes in the early days. Now it’s just on a much, much larger scale.

Once fully assembled, the completed forks pass through a plastic wrapping station with the thru axle protectors already installed. Then they’re placed in a box, and await shipping to their destination.

Rear suspension goes through a similar assembly line process. Above, Monarch Plus shocks are assembled and below, completed shocks are inspected for quality.

Not far away, we step in the shifter assembly area. These lines change based on what products are due to be produced so the day we were there it was Apex SL road shifters next to XX1 triggers.

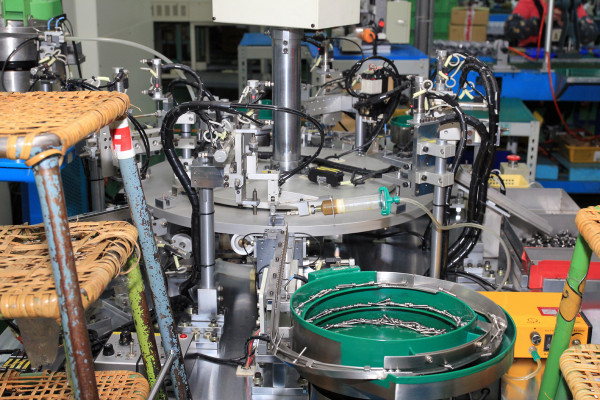

The custom machinery really was pretty fantastic to watch. Like a purpose built Rube Goldberg machine that somehow ends up with tiny parts that are perfectly lubricated and assembled.

SRAM shifters are known for being fairly simple compared to the competition, but even with fewer parts it’s still a complicated process to get the assembled quickly and accurately. At the end of this line complete shifters are already loaded with the cable and packaged for distribution.

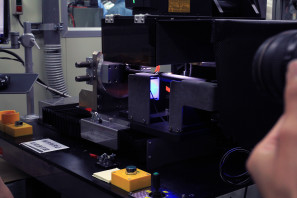

One of the newest parts of the factory is this clean room that was created for the production of products like the Reverb dropper post. The high tolerances needed for smooth operation of the post require a sealed assembly area free of contaminants. Once they’re assembled though, the posts exit the isolation room and get laser engraved on the spot and dropped into shipping containers.

There was a dedicated Front Derailleur line as well, but it wasn’t operational while we were passing through. Product of the 1x trend?

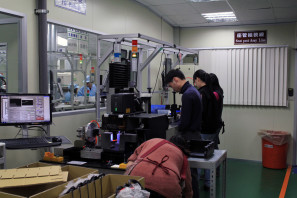

One of the many SPC or Statistical Process Control stations that are found around the factory. Each station is used to check products as they move through the manufacturing process so errors are caught earlier resulting in less overall waste.

While there was a lot going on in this room that we couldn’t take photos of due to it being MY15 (model year 2015) product, we did get to check out the printing section. Ever wondered how they get the logos on hubs like the SRAM Dual Drive?

In the rear derailleur room again we were limited in photos, but there was another cool machine to assemble derailleur pulleys.

Not quite as exciting as seeing fresh new Pikes roll off the line but just as important are the offices for engineers, and quality control specialists. Just don’t forget your slippers.

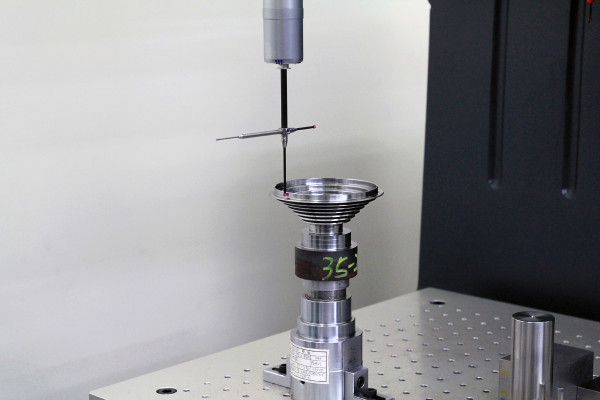

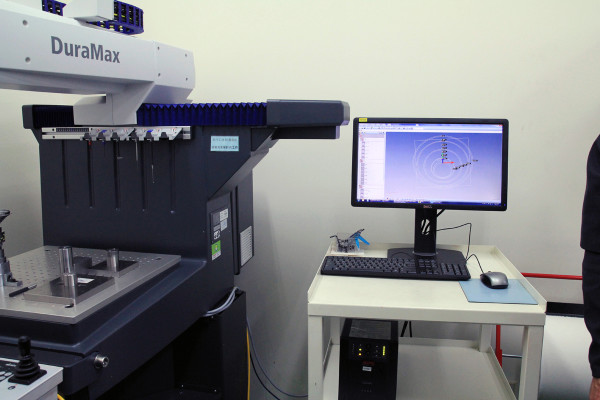

You would assume there is some pretty advanced testing equipment around the factory and you would be right. The test lab by the cassette manufacturing has its own DuraMax CMM (coordinate measuring machine) which points to the precision machining necessary to produce parts like their PowerdomeX cassettes. Having the test center close to the manufacturing aides in keeping the production moving with less time taken out of the process for quality control.

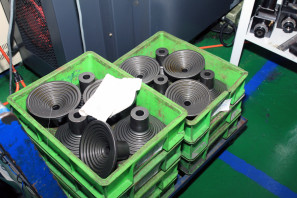

Perhaps the most interesting or at least revealing process was the creation of their machined steel cassettes. If you’re wondering why that XX1 cassette is so expensive, check out the solid block of steel each cassette starts out as. That steel billet is then forged into a rough shape and then machined into that familiar cassette shape. Needless to say there is a lot of machining involved hence the endless bays of CNC machines.

After a lot of this, and these, you get…

…these beauties.

Wheels you say? Why yes, wheels are assembled here as well. At least high end options like the Roam wheels rolling off the assembly line.

The wheels are laced by hand and then go through a sequence of hand and machine truing, tensioning, and stress relieving.

One of the more impressive custom machines was this cassette assembler. The rather large device feeds individual gears and spacers through the different hoppers and out pops the completed main block of a cassette.

Due to the noise and movement of the massive machines involved many of the actual production tools for tasks like stamping and forging are located at two other facilities. However, most of the finishing is done on site at Shen Kang including robotic sanding, and hand polishing.

Anodizing and other forms of polishing are carried out here as well.

Products that need to be painted are loaded on the hanging conveyor and moved throughout the paint facility. More quality control for the appearance of the painted products.

Everything ends up in boxes like these headed to your LBS’ favorite distributor or to bicycle manufacturers. This machine was actually pretty fun to watch, as it snares each box with a packing strap. You definitely don’t want to get too close…

Walking around Taichung specifically, you get the feeling that a large portion of the population commutes by motor scooter, while the rest resort to public transport (which is excellent). On an island where so much energy is devoted to producing bicycle products, using a bicycle for commuting didn’t seem nearly as popular as I thought it would be. Regardless, SRAM tries to make it as easy as possible for their employees to commute by bike to work with a free bike shop, storage, and shower facilities available for use.

Why is this RockShox Argyle in a glass case? It represents the 1,000,000th fork made in both their Shen Kang and Suzhou factories in a single year. After purchasing RockShox in 2002, this hadn’t occurred up until June 20, 2007. We’re guessing they are making a lot more forks today.

After all of that, it still feels like we just scratched the surface. That’s it for Shen Kang, but part 2 will focus on SRAM’s brand new Asia Development Center!