Like so many injuries, it happened when I least expected it. I had spent the whole week riding some of the most difficult trails on the mountain, and here I was laying in the dirt on a trail I could usually ride with my eyes closed. The crash itself wasn’t that spectacular either, probably something I’ve done a thousand times. One thing was certain though, this wasn’t an ordinary crash – this was the big one.

Whether we like to admit it or not, mountain biking (or any type of cycling for that matter) includes inherent danger. Most of the time the rewards outweigh the risks, but if you ride long enough, you’ll probably have a “big one” as well. In 18 years of mountain biking including downhill racing, dirt jumping, and trials/street riding, I had avoided any type of major injury.

This time I wasn’t so lucky. It had been raining all morning. Dusty trails were now true hero dirt. And as I entered into the berm everything was fine, until the berm gave way in a cloud of dust beneath my front tire. The bike went right, and I went straight. From there it’s a little blurry…

After replaying the crash over and over in my head as I lay in the hospital, I decided I must have clipped the top of the berm with my elbow which sent the end of my humerus out the top of my shoulder socket removing a large chunk in the process. Thanks to unbelievably efficient emergency response from the team at Deer Valley and the Park City ambulance crew, I was in the hospital in less than 30 minutes. My shoulder was reset in another 15. In hind sight, if you’re going to have a major injury, Park City is probably one of the best places to do it. My doctors back home credit the quick response as a big reason I’m healing as quickly as I am.

I knew going into the hospital that I had a dislocated shoulder. I wasn’t quite prepared for the broken humerus, and worse – a TBPI, or Traumatic Brachial Plexus Injury.

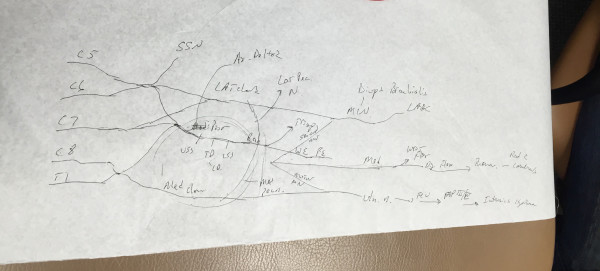

If you’re like me, you probably didn’t know a brachial plexus injury was a thing, let alone a thing that is somewhat common with cyclists. The Brachial Plexus is the system of major nerves that stem from the spinal cord in your neck and control your shoulder, arm, hand, among other things in your upper body. If the nerves are damaged, it can leave your arm or parts of your arm paralyzed which is why I was left wondering why I couldn’t move or feel my hand once I got to the hospital.

I am extremely fortunate however, that I simply stretched the nerves rather than severed, or avulsed them. That meant that my arm was only completely paralyzed from the elbow down for about three weeks. Compared to the nerve damage, the dislocated shoulder and broken humerus were a cake walk. I’m coming up on 5 months since the crash and I’m happy to say that I’m back riding and typing (with both hands and no dictation software!), but in the early days I really had no idea what to expect. Searching the web seemed to only result in stories of the worst case scenarios, and message boards full of people trying to figure out every day activities with one functioning arm. There were a lot of questions, but almost no answers.

That’s the biggest reason I wanted to write this piece – I wanted to provide some frame of reference to anyone else that may suffer a similar injury.

One thing that is hard to understand about nerve injuries is the pain. I was unable to move or feel my arm and hand yet 2 weeks in I was going through the worst pain I’ve ever experienced. This is apparently pretty common with TBPI but it can be hard to control. For me, Gabapentin made it so I was able to get an hour or two of sleep each night, but really only brought the pain down from a 10 to a 7. Now 4+ months in the pain has diminished greatly, but I’m still dealing with it, as feeling slowly returns to my hand.

Depending where you are and your health insurance situation it may be difficult, but this is one injury that you absolutely want to find a doctor who specializes in it. Nerve injuries are hard to treat and there is a limited window for surgical repair, so it should come as no surprise that you should take it seriously.

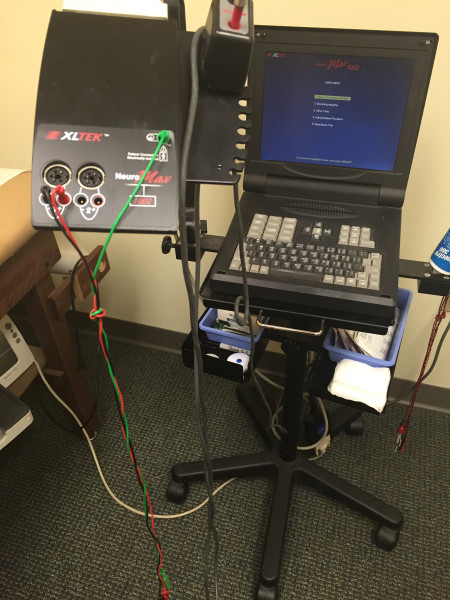

It should also be a no brainer that you should be disciplined with your physical therapy, but based on the other patients I saw, many people don’t take it seriously. Again, I was lucky that the sports medicine group I was seeing also had a physical therapy operation next door and that I was given a therapist who understood what I do, and what I was expecting. You’ll probably also have to undergo an EMG or Electromyogram test at least once – basically stabbing your muscles with electrodes and shocking them with a cattle prod to test the nerve conductivity. It’s awful, but it’s an important test to verify the nerves are still connected. These are usually performed a month or two after the injury, otherwise it may not be accurate if done too quickly.

In addition to the physical therapy, it’s very important that you manually move and stretch the parts of your arm or hand that you can’t move with your good hand. Doing so will keep your joints from locking up and the muscles from atrophying as quickly. Even so, by 3 months my arm looked like the muscles had simply been removed.

In case you’re wondering, regaining the use of a temporarily paralyzed appendage doesn’t happen all at once. What started with a flicker of movement in my pinky finger, slowly progressed one muscle at a time until I could move most of my arm, wrist, and hand in about 2 months. At this point my doctor cleared me to try riding again, but only as long as I could safely stop and control the bike. Thanks to the hand and arm strength of an infant, this was a lot harder than it sounds.

I had been riding the trainer (completely upright so as not to hit the sling with my knees) since the second week after the crash, but when it came time to actually ride outside again my wheels of choice were that of my oldest bike – a 1960’s Western Flyer I have turned into a replica Klunker. The reason? A coaster brake and a completely upright riding position. I did have to wrap the left grip with road handlebar tape to make it 2-3 times the diameter since I couldn’t really close my hand enough to grip the bar, but after that slight modification I was off to ride the local bike trail. I may have been just cruising on a flat, paved trail, but those first few miles were some of the best of my life.

Fast forward a month, and I felt it was time to try something a bit more ambitious. I decided fat biking on the beaches of lake Michigan would be the perfect way to start since it basically wouldn’t require any braking and very little climbing or technical riding. That was better still, but it was time to actually try to ride a mountain bike.

This provided an interesting quandary. My arm was strong enough to support my body and steer, yet my hand really wasn’t strong enough to grab a brake lever. Or more accurately, my index and middle finger alone weren’t strong enough for a standard brake lever, and not being able to feel my fingers meant they would slip off the brake lever without my knowledge.

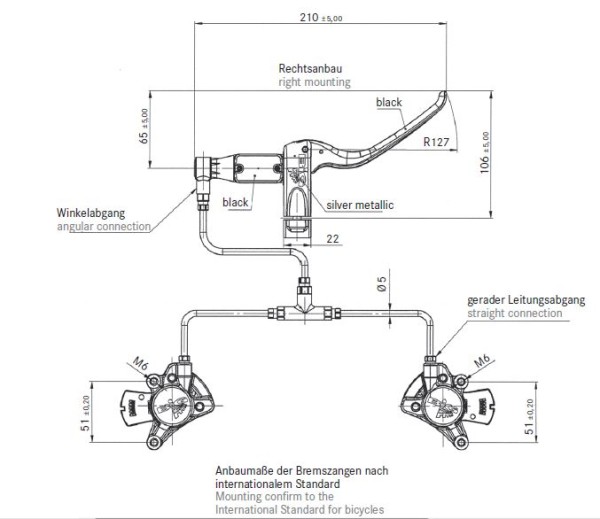

Now we’re getting to the good stuff. After a conversation at Interbike, our friends at Magura USA had suggested that I try one of their eBike brake levers. The levers are longer to allow four finger use, and due to regulations for eBikes they have a ball on the end of the lever similar to motorcycle levers. This meant I could use all four fingers to brake and the ball kept my fingers from sliding off even when I couldn’t feel the lever.

Granted, using all four fingers to brake means only your thumb is holding onto the bar which can lead to some very sketchy situations when trying to brake downhill, but at least I was riding. Thanks to the modification from Magura I was able to get back on a bike at least 2 months earlier than I would have safely been able to.

While not something Magura really advertises, the lever swap is available for any MT 4, 5, 6, and 7 Next brake. Based on the model, the levers retail for $40-55 with or without the ball end. For anyone with weakness in their hands, the ability to use more fingers to stop yourself is worth the upgrade. In my case, the four piston MT7 brakes the levers were attached to along with big rotors also helped me slow down with minimal effort at the bar.

As mentioned, I was one of the lucky ones. Some Brachial Plexus injuries result in permanent paralysis, but that doesn’t mean you’ll never ride again. The story of Tom Wheeler was particularly inspiring though my recovery and proves that where there’s a will there is a way. If you are facing more permanent one handed riding, you can either put both of your brake levers on one side of the bar, or invest in something like the Magura Big Brake or other single lever, two caliper systems. The Big Brake is another one of those items that exists in the Magura line up, but doesn’t get a lot of attention due to its very specific use. The system uses a lever that is big enough to push fluid for two calipers and while it apparently doesn’t offer any modulation between front and rear, the ability to just grab a single lever seems appealing. I’m glad I didn’t have to try this one out, though. Big Brake retails for $240 and includes rotors.

Braking on the road proved to be easier since road levers are basically 4 finger compatible already. Hydraulic disc brakes did make it easier to stop, though. However, I ended up not riding on the road for another month or so which seems a bit counter intuitive. While the road is smoother, riding under 10 mph through the trees proved to be a much safer option than trying to keep up with traffic with a wobbly arm and less than adequate braking in panic situations.

With braking sorted, the drivetrain was the other main consideration. I’m still having trouble using my left hand to shift and probably will for a while. Luckily, this whole 1x drivetrain craze really makes shifting with one hand a lot easier – if you injure your left hand that is. As far as shifters for your left hand that would operate the rear, the only clear option is reprograming a Di2 Shifter so that the left shifter controls the rear derailleur. As far as mechanical shifting for left handed use, you could try flipping a right shifter upside down on the left, or as SRAM pointed out, a Gripshift would work pretty well on the left with the shifting reversed. SRAM’s eTap system also allows for the Blips (remote shifter pods) to be mounted on the opposite side of the bar – you can’t make the left shifter work the rear derailleur, but you can control the rear with a Blip on the left side of the bar.

If your left hand is the injured one, then you’re in luck (at least in terms of drivetrains). Thanks to the number of 1x conversion parts and chainrings for almost every set up imaginable, there should be an easy way to convert your bike without resorting to an entirely new drivetrain. My mountain bike was already set up with SRAM GX 1 so I was good there, but the road bike I eventually made it to the streets with was running SRAM Rival 2×11. In order to make it 1x compatible with minimal effort, I removed the two front chainrings and replaced them with a Wolf Tooth Components Drop-Stop Ring in a 42t. Rather than remove the front derailleur and cabling, I chose to simply turn in both limit screws so the front derailleur couldn’t move and was centered on the single chainring. I’ve had zero issues running the WTC chainring with a non-clutch SRAM Rival derailleur on the road, or as a light cross/gravel type bike as my healing progressed.

When it came time to try to race cross again (unsuccessfully) for the last race of the season, the double of our test bike was again replaced by a WTC ring in a 38t that would work for the asymmetric bolt pattern of the new Shimano Ultegra crank.

At this point I’d like to say I’m back to normal, but realistically I still have a long way to go. Nerve injuries are slow to heal, but so far my recovery has been ahead of schedule which was potentially 6 months to 1 year. This isn’t supposed to scare anyone away from riding. In spite of the risks, I couldn’t wait to get back on the bike and view this as just a setback in my riding career. If you’re reading this after a recent TBPI, know that it’s not always the worst case scenario. You probably have a long recovery ahead, but with a good attitude and the right tweaks to your bike, you’ll be riding again before you know it.