When you hear that Litespeed is based in Chattanooga, Tennessee, you may imagine some sort of stereotypical setting worthy of a scene in Deliverance. That couldn’t be farther from the truth. Do some driving (or riding) around the area, and you’ll quickly see why Litespeed is in no hurry to leave. Officially, the American Bicycle Company has been artfully crafting titanium frames in their factory that sits a short drive from a rapidly growing network of excellent trails, great road rides, white water rafting, and more. Everyone seems to know about Asheville, NC, but from my limited time in Chattanooga, it won’t be long until this area is winning similar praise.

Founded in 1986, 2016 marks the 30th anniversary for Litespeed bikes. Now manufactured by the American Bicycle Group which is the parent company for Litespeed and Quintana Roo, ABG and Litespeed have one heck of a history with bikes ridden by names like Greg Lemond, Robbie McEwen, Lance Armstrong, Steve Hed, Tim DeBoom, Cameron Brown, Jeff Kabush, Bob Roll, and the list goes on. The bikes weren’t always labeled as Litespeeds, but they all came out of the same factory right here in Chattanooga.

This tour is also a bit of an end to an era – Litespeed is moving. But not very far. Just far enough to find a bigger facility that will accommodate their production with a more modern facility and one a bit closer to town with even better access to bike trails. Currently operating with about 38 employees, ABG is alive and well, and Litespeed titanium bicycles have never been more advanced…

One thing that immediately strikes you after spending some time in Chattanooga, is just how modest everyone is here. Sure there are a few jerseys hung from the wall of past champions, but for a brand with such a storied history, you’ll find zero attitude. Maybe it’s that southern hospitality, but everyone at ABG seems to genuinely want to build a better product and gets excited about bikes, or precision machining, or welding, or some other part of the process. Because of that, many of their employees have been with the company for more than 20 years.

Part of the new facility will include a bigger/better equipped show room for both Litespeed and Quintana Roo bikes. In addition to showroom bikes, the offices were littered with a number of employee bikes. If you are to believe the office gossip, Litespeed’s national sales manager Chris Brown is an absolute hammer – though he’ll never tell you that.

As Litespeed started to grow, eventually the company went under the ABG umbrella in 2000, which is also when they purchased Quintana Roo, Merlin and Real Design from Saucony. Merlin was part of ABG until 2011 when it was sold off to Competitive Cyclist which is the same time Real Design was sold so that ABG could focus on their core brands. Litespeed’s head of Product Design and Development Brad DeVaney keeps a reminder of the intricate work machined into the tubes of the Merlin in his office. At one point, Brad had been an engineer with Litespeed for more than a decade, and ended up leaving to recharge his batteries and try something new in 2000. It wasn’t long before he was back in 2004 with renewed enthusiasm, which is contagious. Spend any time with him and you’ll be just as excited about the bikes as he is.

A true bike nut, Brad’s workspace has all the workings of bicycling’s equivalent of a mad scientist. There is even a titanium hard tail motorcycle frame (currently a tire holder). Yes, that was a project they were working on at one point, but after the project’s commissioner ran out of funding, Brad held onto the frame with the idea of maybe one day finishing it. Does titanium improve a motorcycle frame like it does for bicycles? Well, Brad says since it’s not been completed he can’t speak to the ride quality, but the frame is something like 40 lbs lighter than steel.

While ABG is now focused on bicycles, there was a time where they were doing a lot of outside work. After making it a rule of staying away from big “buy to fly” ratios (buying a big block of material and only using a fraction of it in the final product), ABG’s efficiency attracted attention from outfits all the way up to NASA – they even helped with the framework of the Curiosity rover that landed on Mars. Founded by the Lynskey family in 1986, the Lynskey family sold Litespeed in 1999 though Mark Lynskey stayed on as CEO until 2006. Eventually, Litespeed and ABG started to strain under all of the different contract manufacturing that was taking the focus away from bikes. It was at that point that ABG’s current CEO Peter Hurley entered the picture in 2007 after Mark left in 2006. In 2008 ABG made the decision to get away from outside projects to focus back on bicycles exclusively. Since then the brand has been steadily building back their momentum, increasing their quality, detail, and performance. If you’ve had a chance to check out a modern titanium Litespeed, you know that these bikes are long ways from the original straight tube frames of old but they’re still 100% made in Chattanooga.

DeVaney pointed out that they could source things like hangers and dropout pieces from Asia much more easily than turning them out in house, but that’s just not the way Litespeed works. On the titanium side everything is made from sheet and bar stock, plate, and 3/2.5 and 6/4 titanium in house. To create the derailleur hangers above, they start out as the plate titanium shown under the work bench and are machined in the most efficient way possible out of one plate.

Part of doing things the Litespeed way is using the same tools they’ve been using for years – like this Lassy hand tapper. When you turn the counter weighted handle, it’s easy to see why. This is a beautiful piece of equipment.

As you would imagine, Litespeed machines a lot of titanium. Which is hard on tooling. Which requires nearly constant upkeep. Litespeed’s head machinist Gary Ford has kept the machine room running smoothly, and producing a lot of chips for the past 25 years.

Part of making some of the most advanced titanium bicycles is manipulating the tubing in ways you’ll probably never see. Rather than simply using a threaded tube for the BB shells, each shell is internally relieved in the center to reduce weight and to allow for more room for internal routing of Di2 wires if applicable.

Brad didn’t want to give away too much of their secret sauce, but when you look at the shaped tubing of bikes like the T1Sl and ah:wi, the top tubes of those two bikes start out as sheet titanium. The tubes are shaped, formed, and cut in house, each to specific dimensions and properties based on the frame size. Above hang a few of their projects over the years – Litespeed has done a lot of building for other brands from tubing for Tom Kellog’s Spectrum Cycles, to a licensing agreement with Tomac in the mid-2000’s.

In addition to the massive tubing bender, Litespeed also puts their tubing through extensive butting and swaging processes to obtain the desired wall thickness. We got just a very brief demonstration of swaging, but it was enough to see how it works – and just how loud it is. Litespeed isn’t buying tubing that is already butted. Everything is done here.

Tubing is also put through a draw bench which is where the tubes take on a triangular or squared profile. Round tubes are forced through the dies until they are forced into the desired shape. You’ll hear a lot about cold-worked shape specific strengthening or geometrically enhanced tubing in Litespeed’s marketing materials – and between the swaging and the draw bench, this is where most of that work is done. Even the dies for the draw bench are machined in house.

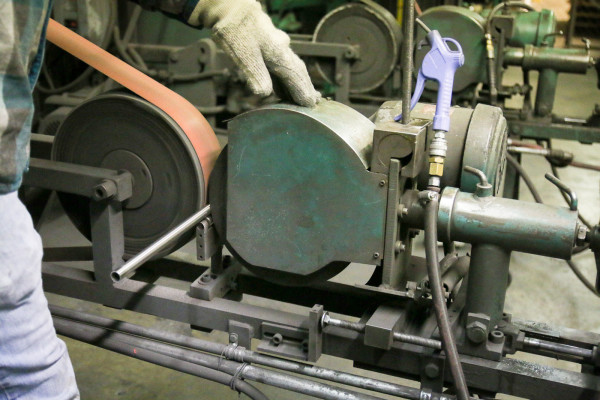

Once the tubing is butted, shaped, and cut machined to length, it still has to be mitered. For the front triangle, David Haight (who has been with Litespeed for 12 years) uses essentially a massive belt sander with some of the longest abrasive belts we’ve seen to create some of the tightest miters you will ever see. David mentioned he usually aims for a gap of 0.005″. Insane.

There are a lot of steps to building a Litespeed that will go completely unnoticed by most, but add up to the final product. Brad points out that there is a 15g target variance – per frame. To get there, each individual tube is weighed, and if out of spec it’s reduced in weight through centerless grinding. When referring to just how strict Litespeed is regarding the precision of each individual tube, DeVaney chuckles half seriously, “no one does that, it’s absurd!” Of course, he means this in a good way, especially since he is the one calling out the weight of each individual tube in the drawings of each frame.

Over in his own manufacturing cell, Steve Grubb (20+ years with Litespeed) works on the rear triangles of the frames. Below right, Brad demonstrates the asymmetric chainstay concept that Litespeed uses across the board to improve the ride qualities of the frame.

Like a lot of manufacturers, Litespeed uses cellular manufacturing to provide an efficient work space for the different frame operations.

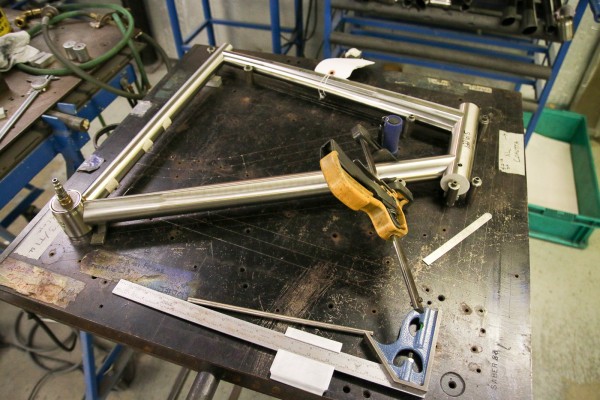

It wouldn’t be a titanium operation without welding. Stepping behind the plastic curtain, frames are laid out on individual frame tables and tacked into position.

Using floating jigs, welders are able to turn the frame to nearly any angle to lay the perfect bead. Litespeed frames are welded up as the front triangle first, then the rear triangle which is done so that at the end of the process, there is only one key measurement that will ensure perfect geometry for the frame. At the current rate, Litespeed can crank out 7-8 frames per day.

There are so many individual processes for building the frames it’s hard to keep track of all the different machines. Brad points out that ABG is very proud of all of the fixtures and machines they have built or adapted themselves, but if there is a tool out there that will do the job better, they’ll buy it. That’s why you’ll find machines from Shuz Tung, Bicycle Machinery, and others.

After welding titanium, the coloration on the frame will lead to oxygen embrittlement. Litespeed removes this alpha case through powder blasting with almost a baby powder like media. Afterwards the frames move to the finishing room where some are polished.

Like any good bike shop, decals used over the years tag a few surfaces. Some more creative than others.

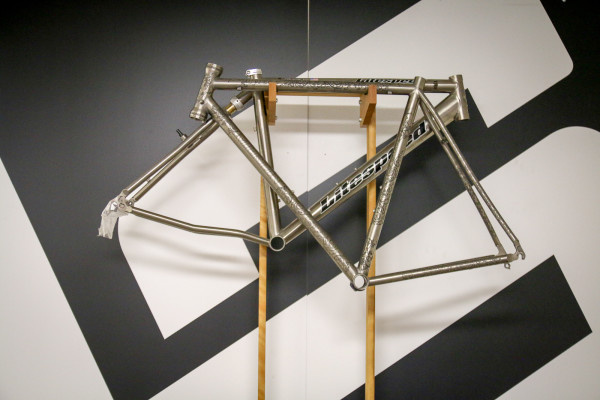

Finishing is just as important as building each frame. Unlike the T1Sl with its machined head badge, most frames receive a titanium head tube badge, and a new decal set that is all applied by hand. On the Pinhoti SL frame you’ll find a trail marker on the head tube that pays homage to the 350+ mile trail that is a favorite for local riders. Getting back to that +/-15g frame variance, each frame gets a final weigh in before it enters the box. “The Truth is Right Here!” Indeed.

The entire factory/warehouse was in a state of flux as they prepare for their move to the new facility. To prepare for the move, Litespeed has increased their inventory ahead of time so that dealers will have plenty of product during the transition which will take place this summer.