By the time the latest suspension fork or disc brake shows up on your bike, it’s ready to ride. Sure, there may be a few adjustments to tune them to your liking, but for the most part the product is completely trail ready. After seeing what goes into testing and development first hand, the amount of effort invested is something we all probably take for granted. We’ve all seen the videos of testing that companies provide for their sponsored athletes, but the lesser known story is how much testing and development takes place before a prototype is ever slated for production. Between the engineers involved and a number of test riders, the idea of covertly testing new product sounds like a dream to the average bike nerd, but what isn’t known is just how tedious, repetitive, and tiring the process can be.

But with the right people and the right setting, it can also be a lot of fun and quite eye opening as well…

In order to help tell the story of this exact part of Hayes/Manitou’s product development cycle, we were invited to join the engineering test team down in Brevard, NC as they put a number of products through the meticulous testing protocol. For this trip, there were a number of products that were up for evaluation – from the nearly ready for launch Mastodon fat bike suspension fork, to prototype disc brakes that were still very early in the development cycle.

Take Notes, and Repeat…

In this case, the actual testing feedback came in two varieties – human and machine. The human element is pretty straight forward. Using the feedback of their own engineers Ed Kwaterski, and Nick Pye, and Test Lab Manager Jim Day, as well as Hayes Mobile Marketing Specialist Phil Ott, the team went through the painstaking process of testing and recording the individual effect of every little suspension change. For parts of the week, that meant starting with a recorded baseline, riding an extremely short section of trail, taking notes on the settings and the results, then making a single small change, and doing it all over again. Now ride that same tiny section of trail while making and recording every single change all day for 12 hours straight. Clean up, eat, sleep, and do it all over again for an entire week.

For me, this was one of the most impressive parts of the trip. By the time I arrived in Brevard, the team had already been there for three days. Three long days. And two more big days were yet to come. From the sounds of it, Hayes’ bike division is spending more time in recent years doing similar testing on location, but even so the time there is precious. Getting the team together and driving many, many hours to a place like Brevard (which is a perfect spot for this type of testing) doesn’t happen often, so it was clear that they were there to work.

Data Acq Acq Acq Acq

While human feedback is vitally important to the process, having a scientific way of recording what’s actually happening with the bike is equally significant. This is where the Hayes/Manitou Data Acquisition bike comes into play. Littered with colorful wires, bulky plugs, sensors, linear travel potentiometers, and looking more like something out of the Ghostbuster’s arsenal than a bike, the Data Acq bike as they like to call it, is a key piece of new equipment for Hayes. The first time Manitou used data acquisition was during the development for the new Dorado in 08/09, but it wasn’t until a couple of years ago that Jim got some help from the Powersports division of Hayes to prove it was a necessity for future development of all products.

Initially, the team started with a data acquisition system that was borrowed from a BMW race motorcycle. They took it off the bike and put it in a backpack that ended up weighing 30 lbs – “it was pretty awful.” Just imagine hitting a large jump with a 30lb backpack and you get the picture.

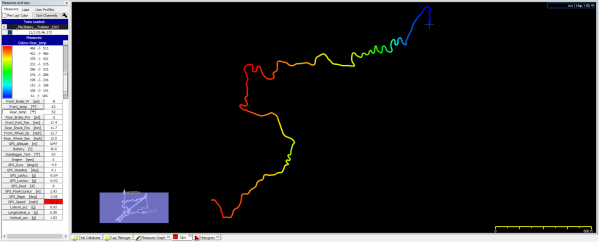

The latest iteration builds off an AiM EVO4 Data Logging system that has built-in GPS which allows Hayes’ engineers to see exactly where the rider is on course when each little suspension movement is detected. But the system measures more than just suspension movement. All in, there are accelerometers to detect changes in speed, wheel speed sensors, and brake pressure and temperature sensors for brake testing. The end result is a heavy, expensive, and somewhat fragile bike that is capable of telling you exactly what is going on at any given moment on any terrain.

Just Look at All that Data

The resulting data is so revealing, that about a year and a half ago, it completely changed the way Hayes looked at brake testing. In fact, this is one of the things that Jim says was the most surprising things to learn from the Data Acq bike. The bike’ results have resulted in dramatically changing the way they test brakes – which led to huge gains in performance as well.

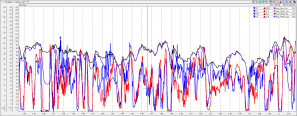

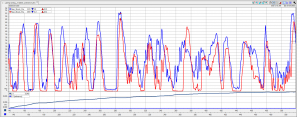

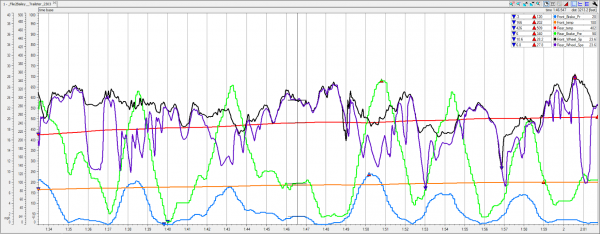

Expressed in terms of data on a graph, Hayes provided a few samples of what the Data Acq bike is capable of, above. Starting at the top, this beautiful visual represents the data from the rear brake pad temperature while riding Dr. Jekyll to Cowbell at Bailey Mountain Bike park. The line represents the trail from the GPS sensor on the bike, and the color shows the brake temperature as it heats up going into sections with more braking, then cooling off when the rider is off the brakes. Combined with the brake channel data from Dr. Jekyll to Cowbell (bottom), Hayes is able to track the overall brake performance including system pressure, pad temperature, and wheel speed to better understand what is happening as the rider moves down the trail. This can be important to discern a rider’s brake bias, when the rider is using the rear brake to initiate turns, and other human inputs to braking that machine testing can’t replicate. The middle two charts show suspension channel data from Dr. Jekyll to Cowbell (left), and a comparison run on Sycamore Cove (right). To give you an idea of just how much information the system collects, the graph on the left is scaled down to the second – you’re looking at suspension inputs from just 27 seconds of riding. This can be scaled up or down, but it gives you an idea of just how detailed the data provided by the Data Acq bike can be.

On the right side, this graph is a telling example of how properly tuned suspension can improve your performance. The data from two identical runs by Phil are overlaid on top of each other, with the blue line representing rear shock pressure 40psi too low, and the red showing the ideal setting. Over just 380 ft of trail, the proper setting caused Phil to be more than a half second faster. Multiply that by the full run and you get the picture.

The Team

As important as the Data Acq bike is to future product development, it’s mostly useless without the right people behind the scenes to interpret the data and know how to translate that to changes in shock tune. The Data Acq bike itself is the baby of Jim Day, the Hayes Test Lab Manager. With a varied background that even includes a stint as a horseback riding instructor, Jim is fairly new to the bike world but has quickly taken to the position at Hayes. Able to see the world in terms of its precise data points on a graph, Jim serves as the Data Acq bike’s handler, quickly downloading ride data after the runs – and also knowing when the equipment may be having an issue. As you could imagine, a mountain bike with a full array of sensitive equipment mounted to it can be a handful to keep up and running. But armed with a sea of zip ties and full tackle box of replacement parts and spares, the bike survived the week’s testing with minimal hiccups.

Then there’s Ed Kwaterski, a suspension tuning savant who got his start as a hobbyist setting up his and his friend’s motorcycle suspensions. It wasn’t long before Ed had his own suspension tuning company, and eventually took a position with Showa and Harley Davidson. As fate would have it, Ed was offered a promotion at Showa that would have required a move from his home state of Wisconsin, which led to him accepting a position at Hayes as the Chief Engineer at Manitou.

You can get a pretty good sense of a person through their tool box, and Ed’s traveling collection of shims for shim stack dampers speaks volumes. During the early days of testing, this shim kit was put to good use with a number of changes to the shim stacks on various suspension products until the team found what they were looking for.

The team jokes about Nick Pye being one of the last two remaining things from Manitiou’s original ownership, but with that comes a huge knowledge of past and current suspension design. Not only does Nick play a big part on the engineering side, he can also ride which is important when it comes time for these test sessions. Perhaps it’s his English upbringing, but Nick always seems to be even keeled – even after laying it down on a massive step down due after going way too deep to a greasy landing. I watched on in horror thinking I had just seen Nick get badly injured, only for him to get up without saying a word other than “I’m OK,” all while quietly assessing what went wrong. Later in the day he would go on to stomp the landing cleanly – twice. On two different bikes.

Joining the engineering team for the test sessions was newly appointed Mobile Marketing Specialist Phil Ott. A former shop owner, current riding instructor, and the man responsible for visiting shops around the country and teaching mechanics the ins and outs of Hayes, Manitou, and Sun Ringle products (in the Ford Transit above that he meticulously maintains), Phil also happens to be a pretty good rider. Ok, really good. Serving basically as the pro rider for the test sessions, Phil is able to jump on any bike and ride it far past the limits of the average human.

I’m pretty sure the Jumanji trail at Baily Bike Park has never been ripped so hard on a full suspension fat bike.

But more important than just being fast and a great mechanic, Ed praised Phil for being able to communicate to the engineers exactly what the bike was doing underneath him with every little click of tuning. Ed pointed out that there are a lot of riders who are great pros but terrible test riders because they can’t articulate what is actually happening underneath them – they know it’s good or bad, but not why. Because of that, Ed went on to say that it’s actually easier to tune for a racer since it’s one person. When you’re trying to develop a suspension tune for group of people it becomes much more difficult. Especially when you feel that suspension should be improved year over year, not just when there’s a new fork, as Ed does.

Bailey Mountain Bike Park

This all led them to search out a spot like Brevard, NC where they could find a spot with rowdy roots and rocks, but also spots they could test in a short section, over and over again. After three days of testing and dialing in the shim stacks in the trails around Brevard, we headed to the Baily Bike Park in Marshall, NC for some high speed testing. Thanks to private shuttle from Greg and Baily, the team was able to run two trails over and over, both on the Data Acq bike and other test mules. With the two vans set up in the parking lot, notes were taken on the set ups, then we’d shuttle to the top, nail a run, then head back to the vans to take more notes and make an adjustment. During this time, the team was also testing various brake pad compounds for use in their new brakes – something the brake pressure and temperature sensors on the Data Acq bike came in handy for. Testing right up until dark (and our time at Baily had run out), there was time to pack up, grab a quick meal in town, and then it was straight to bed for another long day of testing in the morning.

DuPont Forest

On the final day, we found ourselves in the DuPont State Forest where they would test the remaining suspension bits that they hoped to collect data from. When asked if there were specific goals for the testing session from the outset, Ed stated that there were multiple things they hoped to accomplish. One of the biggest achievements would be to settle on suspension tunes for the new products that would minimize compromises from one trail to the next. The tuneability of Manitou’s suspension is such that they could really hone it in to a specific trail, but they need to make it a more versatile tune since most riders won’t be making changes to their suspension from trail to trail.

Of course, another big component to the testing was to dial in the performance of prototype parts – something they tried to keep coy about. After all, I was a member of the press who lives for the rumors of new parts and bikes. Further, it was a training event for Phil and the rest of the team as they build data acquisition into their standard repertoire of testing.

If there was one thing to walk away with from my time spent with Hayes/Manitou in Brevard, it’s that they are fully committed to the future and are quick to admit past faults. All while looking to advanced testing technologies to raise their products to the next level. Judging by what we’ve seen so far, Hayes/Manitou has some very exciting things in the works – but for now, you’ll just have to wait and see.