‘Welcome. Here’s a bike. It has 180mm of travel. Now go climb a trail that many locals haven’t climbed from the bottom because it’s so steep, and there’s an easier way to do it.‘ That was the way we were greeted once we made it out to Westfir, Oregon for the launch of Polygon’s latest bike. To this point, Polygon had kept their cards very close to their chest. We knew that we were there to ride a new enduro bike, but honestly had no idea what to expect. I for sure wasn’t expecting to start off the day climbing more than 2,000 feet straight up on a bike that technically has more travel than some DH bikes.

Then there was the set up. Typically on these launches, the companies use precise measurements and fuss over the details to make sure the bikes are perfectly dialed in. Not here. Instead, after starting with a rough baseline sag, NAILD founder and industry veteran Darrell Voss watched us accelerate from a stand still, both sitting and standing, then watched as we rode over a square edged concrete block. Without saying anything else, we were sent out to climb Alpine from the bottom which at least according to Strava has sustained sections of climb with 15% grade all the way up to 23%. I mentioned this bike has 180mm of travel and no form of lockout, pedal platform lever, or travel adjust, right? Oh, and our tires were pumped up to a ridiculous level as well.

Figuring there had to be a method to the madness, we set off a few riders at a time wondering what the hell we were getting ourselves into…

What Goes Up, Can’t Wait to go Down

It wasn’t long into the ride before I was able to get over the initial shock to my system of blasting straight up with no warm up, and started to think about the bike. Yes, I was hurting, but most of it had nothing to do with the bike. Based on how well it was climbing the steep slopes, it was clear that the Polygon Square One is built for climbing. With no discernible pedal bob whatsoever, the bike also managed to make good on that mythical ability to soak up bumps while traveling up hill, while staying completely efficient, and offering loads of traction at the same time. It was definitely a bit of work to keep the front end from wandering thanks to the super wide bars, short stem, and 180mm fork, but the angles while climbing seemed steeper than comparable bikes. Tight switchbacks were dispatched with ease, and in spite of the rock hard tire pressures, very rarely was I left wanting for traction.

The reason for the high tire pressures turned out to be that Darrell wanted to show that the Polygon wasn’t relying on low pressures to aid in grip or to provide a smooth ride, somehow compensating for poor suspension design. After completing the first ride on pressures almost double what I would normally ride and experiencing Darrell’s point, I went back to more normal pressures as the riding got more loose and slippery as storms moved in.

Ground Tracing Devices

As good as the bike is when pointed uphill, it left me a bit unprepared for what would transpire as things started to point downward. Without skipping a beat, the Square One morphs into the most ground hugging enduro bike I’ve ever thrown a leg over. It’s this characteristic that leads Darrell to claim, “we don’t build suspension systems, we’re building ground tracing devices.” That phrase, “ground tracing device,” is probably the best way to picture what riding the Square One feels like. It’s almost as if the rider is suspended in the same position in space, and the two wheels are just perfectly tracking over the ground – never leaving it, or getting hung up, just in a state of nearly perfect flow.

Clearly, Polygon and NAILD are onto something – though we wouldn’t find out the specifics until after we completed two more rides. Ride number two for the day had us shuttling up to an upper point on Alpine, only to find deep snow preventing us from reaching the drop off point. So we got out and pushed. It was about 1.5-2 miles before we found rideable trail but then it was all smiles as we turned onto Tire Mountain and found glorious sunshine and an extended loamy descent. Day two found us in much less desirable conditions as storms had moved in over night, knocking out power to Westfir and bringing in soaking rains in the process. That rain turned to snow as we climbed in the van towards the drop off point for Heckletooth, but as soon as we started down the rocky section of the trail, the weather started to improve. A bit more technical than the other trails we had ridden, Heckletooth dropped out at the bottom where we traversed over to a brutally steep road climb nicknamed “the wall.” The climb was worth it though as we were rewarded with a fast and fun descent down Aubrey Mountain.

The terrain in Oakridge has a lot to offer, from seemingly endless ribbons of loamy singletrack with brutally fast stretches and tight switchbacks, to more rocky terrain that would challenge the suspension a bit more. But to be honest, nothing here would make me think, I need a 180mm travel bike for this – but that was kind of the point. As Darrell points out, “[with the NAILD R3ACT-2Play system] travel numbers are not relevant any more.” On the surface that sounds ridiculous, but after riding a 180mm travel bike that pedals better than some 120mm travel rigs, it gets you thinking. If you can have the best of both worlds – the climbing prowess of a trail bike and the descending capability of a DH bike, why not?

Darrell and the team involved in the bike are painfully aware of how cliche that all sounds, which was the reason for all the secrecy and lack of information leading up to the press camp. They didn’t want us to be tainted with any sort of preconceptions. Hell, they didn’t even want us riding as a full group on the first ride so that we would form our own opinions and not discuss it with the rest of the crew. Claiming to be the result of more than 20 years in the conceptual stage and the past handful of years in actual development, Darrell said “it worked better than I ever expected it to,” when the first working prototype was created.

NAILD x Polygon

A collaboration between NAILD and Polygon, the wheels were set in motion for the bike in 2010 when Darrell met Zendy Renan, the Product Development Manager for Polygon Bikes. Polygon might be a relatively new name to many riders in the U.S., but the Indonesian company has been building bikes since 1990 out of their own factory in Surabaya. What started as contract manufacturing for other brands grew into the addition of their own brand Polygon in 1992/93. Selling mostly to Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, Polygon went international in 2010, though domestic sales are still their main business. In 2012 Polygon started selling into the U.S. through a handful of dealers – but also through Amazon as well (this bike will also be available through Amazon later this year). Wanting to expand into other categories, Zendy knew they had to start from scratch – and true to the meaning of their name, they would have to look at it from all sides. Fortunately, Darrell and Zendy saw eye to eye in the desire to create bikes that make riders happy and “make their life simpler, so they can have a better experience.”

Because of that desire, there was a bull’s eye placed directly on lockout or pedal platform levers. Pulling no punches, Darrell went on to say that too many bikes in the industry are relying on shock technology rather than good suspension design to get the job done. “The only reason you know how to use a lockout lever is that someone else didn’t know how to make a good kinematic.” Harsh words, but when you look at what he’s been able to accomplish with one of the most basic shock settings, he may have a point. Darrell continues that the current thinking is that everything has to come from the restriction of hydraulic fluid, or shock damping – but restriction of fluid equates to friction, which equates to a loss of energy. Because of that, the Polygon Square one is equipped with 60% less damping than a standard shock, and apparently they could be de-tuned even further. We’ve been at events where demo crews were intimidated by the set up on the Fox Float X2 air shocks, but not here. Simply open both the rebound and low speed compression damping circuits completely and you’re set. Without a lever on the shock to mess with, it couldn’t be simpler. Everything seems like such a departure from what we’ve been taught over the years that it inspired the name – Square One, or a new beginning of kinematics for the industry.

R3ACT-2Play

Calling it a four bar suspension system (slider, slider housing/swingarm, main link, and frame member making the four bars), Darrell is quick to point out that it’s not like any other four bar system out there. There’s the obvious addition of the frame slider hidden behind the bottom bracket, but more importantly it has to do with the kinematics. Called the R3ACT-2Play suspension system, the 3 refers to Newton’s third law – every action has an opposite but equal reaction. Focusing on the acceleration of mass, body mechanics, and the inertia forces acting on the frame, Darrell claims that “everyone looking at kinematics is looking at the wrong loads. They should be focused on the rider mass, not the mass of the bike.”

If you haven’t noticed by now, Darrell is quite opinionated when it comes to suspension, but then that kind of comes with the territory. Working with Klein from 1985-95, Darrell went on to work for Spinner suspension, Suntour suspension as the President and Director of the North America division, as well as completing a number of contract suspension projects for other brands in the industry. But all of that experience seems to come back on this one project. The ability to create what they see as a true “quiver killer.” A true all mountain bike. That sentiment seems to be shared by Polygon UR team rider Mick Hannah, who mentioned during the presentation that, “I’ve started thinking about racing EWS seriously, and this bike has gotten me excited about more types of riding. I just love riding bikes. Having a bike like this, I can ride whatever I want and don’t need to have 5 different bikes in the garage. Hard tail, a DH bike, and this would take care of the rest.” Granted, Mick could ride a Huffy faster and more stylish than you or I, but he also seems quite genuine about his experience with the bike. Like us, he had not ridden the bike prior to camp – though that didn’t keep him from destroying berms, jumping everything, and making the ground quake under his tires.

Coming from a completely different angle, Kurt Sorge was also on hand at the camp to provide the freerider’s point of view. That’s not really a fair categorization though, since Sorge rips on a bike whether he’s flipping a massive step down, or just out for a trail ride with friends. When asked what he thought of the bike’s braking abilities, Sorge replied, “it was just too easy to ride, I wasn’t really paying attention to the braking.”

With NAILD providing the suspension system (and the rear axle), it was up to Polygon to create the bike. Stressing that this is a Polygon bike, not a NAILD bike, the frame does see a custom link and custom pivot – something that won’t be seen on other projects NAILD is currently working on with other brands. In this case, NAILD provides the kinematics and parts, and Polygon builds their bike around it. Using an ACX carbon frame for 27.5″ wheels, the NAILD R3ACT-2Play suspension system is one of those designs that at first, you might not really notice what’s going on. But look closer and all of a sudden you realize there is a slider with a 43mm stanchion housed between the swingarm and the frame. While it looks like it could be a second shock, it’s actually just a slider.

There is about 3-4cc of Race Tech oil inside to keep things lubricated as well as an SKF motorcycle seal to keep out debris, but the main purpose of the slider was for stiffness of the frame. Darrell says that the frame could have worked without it, but it wouldn’t provide the proper balance of stiffness, and the slider is a fairly light weight way to go about it. In spite of how long the tapered slider is, it has only a 35mm stroke with a unique pressure relief valve built into the pivot point. Like a fork bleeder, this is to remove any pressure inside from changes in altitude to keep things running smoothly. Darrell says that the slider will need maintenance like any moving part, but it shouldn’t be maintenance intensive – as long as you use the included rear wheel fender. It even includes a warning, “Do Not Use Without Fender.” Fortunately it seems to work pretty well. After two days of loamy, wet, rainy, snowy, and muddy riding, the slider area was surprisingly clean.

Of course, you can’t miss the elevated stay which was used because it’s stiffer, adds more tire clearance, and makes for shorter stays. Not to mention it makes for a quieter bike without much for the chain to rattle against. Mated to a Boost 148 rear hub with the NAILD 9 3 12 thru axle system, the rear end felt plenty stiff during our rides. Additional details include a Pressfit GXP bottom bracket, internal cable routing, ISCG05 tabs, Boost spacing front and rear, and integrated carbon armor. Sorry, no bottle cage though.

Accurate Geometry

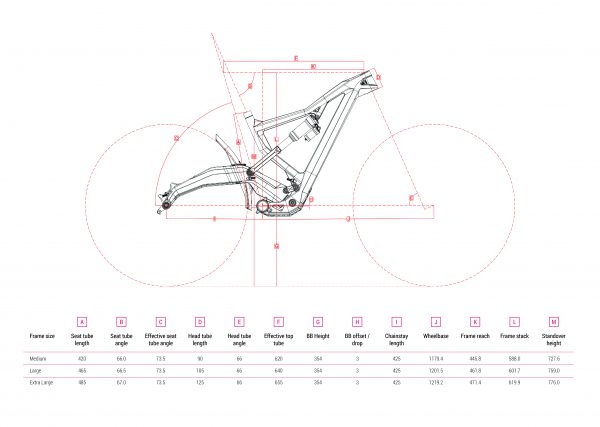

When it comes to the geometry, that’s another sticking point for Darrell. Citing the propensity for companies to provide geometry numbers at showroom (how the bike sits without a rider) and not at sag, Darrell comments that “the problem with our industry is that we’re giving bunk data.” Due to the bike’s desire to keep the same angles when climbing or descending, the Square One is said to have a 66° head tube angle at any time, along with a 73.5° effective seat tube angle, and 425mm chainstays. Given the room in front of the rear tire, Darrell says they could go even shorter with the stays, but were looking for the ideal performance and weight balance. Part of the seat tube angle equation is a custom KS dropper post with a 15mm offset head. This gets the seat back far enough while providing enough clearance for the rear wheel and fender against the seat tube at full compression. Looking at the frame with the truncated seat tube, I thought for sure I wouldn’t be able to run the full dropper post – but all the frames have been built to allow each dropper to be slammed to the seat collar. Coupled with a 125mm dropper for the medium I was on (150mm for L & XL), and there was plenty of room for the full extension.

Of all the times for me to forget my scale, I was kicking myself for not having it on me for this launch. We were told that the bikes came in at 30lb 2oz (13.66kg) for a medium without pedals, but they can be built lighter. Polygon seemed hesitant to talk about the weight as much like the travel number, it doesn’t really paint an honest picture of the way the bike rides. Back to that travel number for a second, if 180mm sounds like a lot, get a load of this – Darrell says that the bike actually has more usable travel than some 200mm DH bikes. That’s due to the Square One running a smaller amount of sag at 20% relative to DH bikes which often push 35%. And yet, the thing still climbs like a trail bike. Amazing.

Regarding the front travel and that wandering feeling I mentioned while climbing super steep stuff, Darrell said that the bike can run a 180mm fork as stock, or a 170mm fork will work as well. That would steepen the head angle a bit, lower the BB by 4mm, and be better suited for places like Oakridge if you’re planning to do a lot of climbing. Granted, that feeling was only experienced on the absolute steepest part of the trail – not something you’d typically experience. The rest of the riding in Oakridge had me relishing the extra travel on the descents and not minding it at all on the climbs.

At the end of the day, the Polygon Square one was honestly unlike anything I’ve ever ridden. The closest thing I could think of would be the Missing Link suspension system from Tantrum, but it’s not really a fair comparison given the Polygon’s massive amounts of travel. As usual, two days of riding hardly gives an impression worthy of a full review, but first impressions are usually pretty indicative of the final results. I left the camp still struggling to comprehend the thought of a 180mm travel bike as your “one” bike, but the experience indicated that you totally could. It climbs as well as anything out there, it snaps out of corners with ease, and the suspension goes from efficient to ridiculously plush almost telepathically. There’s really no reason to want any less travel out of an all mountain/Enduro bike. I wouldn’t be surprised to see shorter travel R3ACT-2Play bikes pop up in the future, but the climbing abilities of the Square One will have riders considering far more travel than they typically would given the circumstances. The fact of the matter is that we climbed some of the steepest stuff I’m likely to encounter on most rides, and I never wished I had a different bike. Different legs, yes. But different bike? Not at all. The Square one is a bike that will leave you shaking your head – and grinning ear to ear after you blast back into town from the top of the mountain.

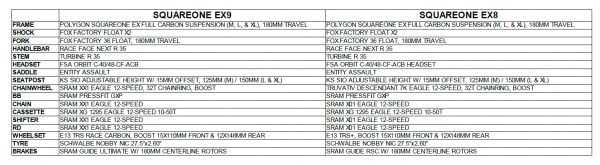

Available this June, the Square One EX will be offered in the EX9 and EX8 builds in M-XL frames, both with SRAM Eagle 1×12 drivetrains. The EX9 gains the XX1 version as well as carbon wheels and a few other upgrades, though both builds will be more than capable. Pricing is TBA.