As a self-proclaimed chainring connoisseur, Doug Brown Jr. has ridden them all. Round, oval, o’symetric, Rossett Ogival, Bio-Pace, you name it; he’s tried it in the pursuit of the perfect biomechanical advantage. But what if there was something that had never been done before? Something that would provide a noticeable advantage in cadence, speed, and endurance? That is the ring that’s kept Doug (and Senior Mechanical Engineer Josh Yablon with Paul Hammerstrom Design) up at night, and it’s called – Spreng Reng.

What makes Spreng Reng so different? Well, instead of providing a consistent ring size for both legs, it instead focuses on your stronger, dominant leg. Think bigger ring just for your dominant leg, and a smaller ring for your weaker, non-dominant leg. The whole idea boils down to this – higher cadence plus additional “dynamic gear rollout” provides increased endurance from reduced fatigue, which in turn will allow you to climb faster.

Yes, it’s as crazy as it sounds. But bizarrely it seems to have some merit. I went into this story fairly skeptical and decided to mount up a standard ring and then the Spreng Reng and do back to back testing on the same loop with the same bike. While the Spreng Reng didn’t feel that much faster out on the road, there was actually a 1.7mph average speed increase over 10 miles. Granted, this was less than a perfectly scientific test, but it was surprising to see that much of a difference, especially when it didn’t feel any faster while riding.

The resulting chainring is sort of an oblong ring that is adjustable but is mainly meant to place the larger ring radius during only the power stroke phase of your dominant leg. The smaller radius is present during the other leg’s power stroke and also within both dead spots. The actual ring profile has undergone a substantial number of revisions since we first started to discuss the concept with Doug back in September 2017 (it’s at version 24 last time we checked), and the ring design is still evolving (more on that soon).

When it comes to climbing, Doug loves the long, painful ascents up local mountains like Mount Mitchell, which is where a lot of the testing has taken place. The ‘a-ha’ moment for Doug was when he was able to climb one of his local roads with a substantially harder gear choice at the cassette while on one of his early prototype rings. Typically, he says that the same gear choice would have left him thoroughly gassed before he got to the top, but with Spreng Reng, he made the climb faster than ever.

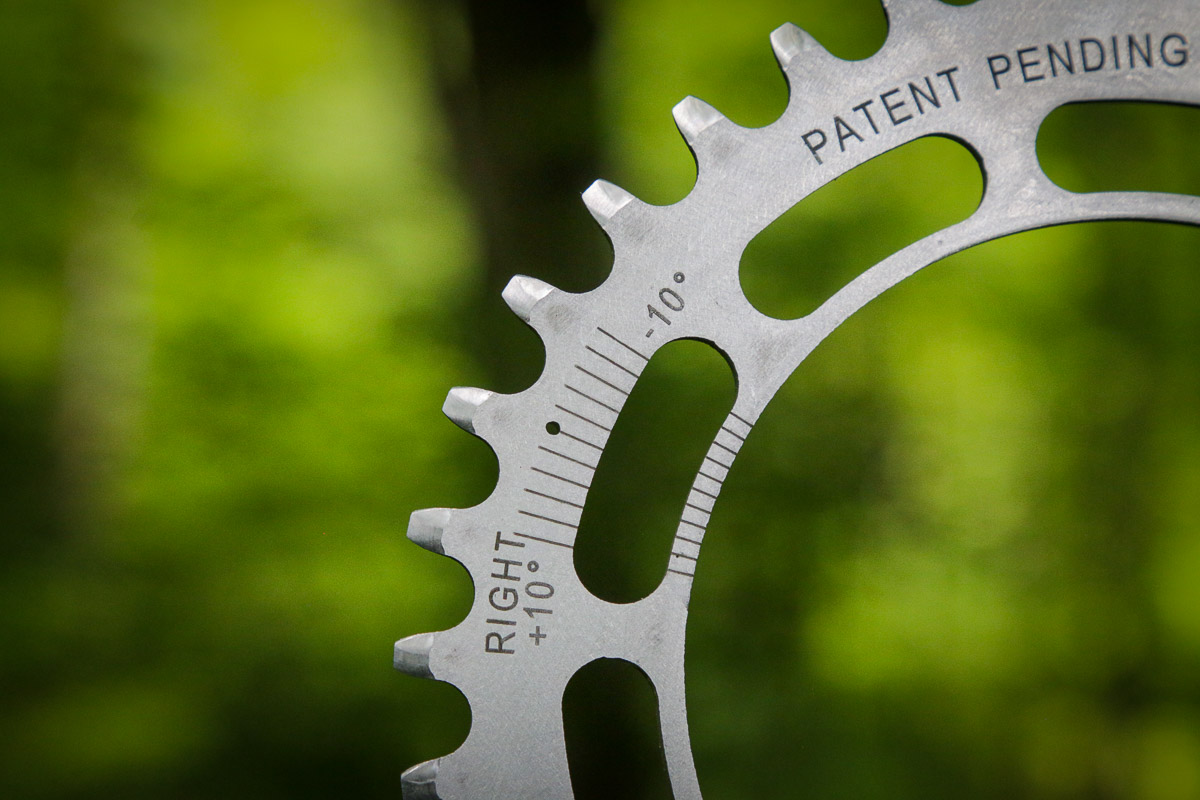

The most recent version transitions between a 36t and a 39t profile, with an effective gear tooth range of 37, and includes adjustable “banana holes” which allow you to position where the larger 39t profile starts to engage in the power phase of the pedal stroke. Due to the design of the current mounting holes, you’re required to use the included steel chainring bolts to ensure proper torque to hold the ring in place. Unfortunately, since the bolts were for a double chainring set up and I was running the ring as a 1x, I had to use aluminum bolts that I had from WTC in a pinch. This is definitely not recommended, but it did work for the duration of testing.

The theory is that the combination of the 39t for your strong leg and 36t for your weak leg actually allows you to turn the pedals at a higher cadence but with less effort resulting in improved climbing. This dynamic ratio allows you to power through the larger radius faster than you normally would which briefly accelerates the bike, then you get a bit of a break with the smaller radius which helps to keep your cadence up. Essentially, you are able to pedal through the larger radius at the higher cadence provided by the smaller radius.

This is then a give and take, the smaller radius side allows you to speed up your cadence, while the larger radius side then transfers that higher cadence into higher speed through more gear rollout. The result is supposedly the ability to ‘spin’ a harder gear than you would typically run with less fatigue. Doug claims the design “is a melding of what is possible within the laws of physics by creating a desirable bio-mechanical benefit for the rider.”

The trick is creating a transition in the ring that prevents a “lopey” pedal stroke at higher cadences. While V20 isn’t there yet, this is exactly what Doug and Josh think they have finally accomplished with the latest version 24 of the chainring which Doug has tested up to 112 rpm (we have not been able to test V24 for ourselves yet). The newest version, scalable up or down in total gear teeth range, now has a more consistent 36t radius that better blends into the 39t radius creating a smoother pedal stroke. There’s also a patent pending 1/2mm horizontal offset shift that will create a 3 ½ tooth radius difference to make the same chainring into a 39.25/35.75t ring for even more of the cadence/gear rollout benefits.

Designed as a flip flop ring, riders with dominant legs on either side will still be able to get the same benefits out of one ring by simply installing it in the opposite orientation. Further adjustments will be able to be made by changing the mounting position ‘clocking’ which allows you to tailor the transition from the 36 to the 39t profile to your liking.

While there does seem to be some benefit to the ring’s design, it certainly isn’t without its drawbacks. One of my initial concerns was that if this ring is relying on your body’s natural imbalance, wouldn’t exploiting that eventually lead to your body adapting to the ring, therefore rendering it ineffective?

Doug says that is a legitimate concern, which is why he envisions this as a ring that you would only use for particularly long days with a lot of climbing, special events, or race days while continuing to train on a typical round inner ring. It’s a bit of a stretch to think the average individual will be swapping out their chainrings on a regular basis, but it’s not unheard of for committed racers to change equipment based on the course. However, if the design was integrated into a direct mount ring for cranks like the Easton EC90 SL, swapping ring could become an easier proposition. Doug sees the ring as either an inner ring for a double set up, or as a stand along ring for a 1x drivetrain – but all for the road.

Of course, the ring can be used in the complete opposite manner as well. Instead of placing the larger 39t profile on your strong leg power stroke, you can place it on the weak side for an entirely different purpose. Theoretically, giving the weak leg the larger chainring profile should act as sort of one-legged drill which could potentially even out your power from leg to leg. I’ve tried it in this configuration as well, and it’s definitely a weird feeling – much different than the other way around, but seems to deliver exactly as promised.

Ultimately, in the world of ovals and ellipticals, the patent pending Spreng Reng is in a world of its own. As far as I know, there’s nothing else like it which either makes it brilliant, or insane. Either way, it’s been a fascinating look into the development process of a ring where the development team is truly thinking outside the box and past the traditional pedal stroke.