Road racing has always been a bit of a cycling arms-race, with manufacturers looking to provide cutting edge technology that toes the line of the UCI regulations to give their competitors the advantage they need to be first to the line. With the wild shapes and departures from decades of traditional frame design that emerged in the 80’s, the UCI adapted and created new guidelines and rules. Not only regarding race craft and rider conduct, but more and more stringent regulations for equipment were created and instituted to keep the playing field level, and keep the focus of racing on the rider’s skill and ability – not the R&D budget of the sponsors. Without a doubt there is certainly a bit of politics and controversy behind new rules and regulations – we don’t have to look far to land on the mess of disc brakes’ introduction to the peloton, and the latest changes are no exceptions.

This 2021 season comes on the tail of a 2020 season shortened due to the pandemic, and with a flip-flopped schedule that saw the traditional road racing calendar flip flopped beyond recognition. The parcours strangely un-crowded, with few spectators if any allowed to line the barriers, the racing was… spectacular. In perhaps the strangest season ever in recent memory, riders showed that they had not spent the extended off-season sitting around and a really special grand tour season saw new faces atop the podiums and breathtaking finishes abound.

As tradition has held through years past, the UCI released amendments to its rules and regulations leading up to the start of the 2021 road season – this time with a curious twist. Where typically rule changes have circled around new technology developed since the prior season regarding aero profile ratios, minimum weights, and equipment on the body or bikes alike, this year the focus is instead on the riders, and specifically the riders’ position.

Let’s take a moment to take a look back at the 2016 Tour de France. Think back to the days of Team Sky (now Ineos Grenadiers) helmed by Chris Froome, dominating stage races and in the midst of a three win streak in the TdF (2015-2017, with one prior in 2013). Built like a classic GC contender, slim and lithe, meant to go up at speed and leave his competition on the climbs, Froome surprised everyone when he left a group of yellow-jersey favorites and put 13 seconds into them on a 15 kilometer descent to the finish of stage 8.

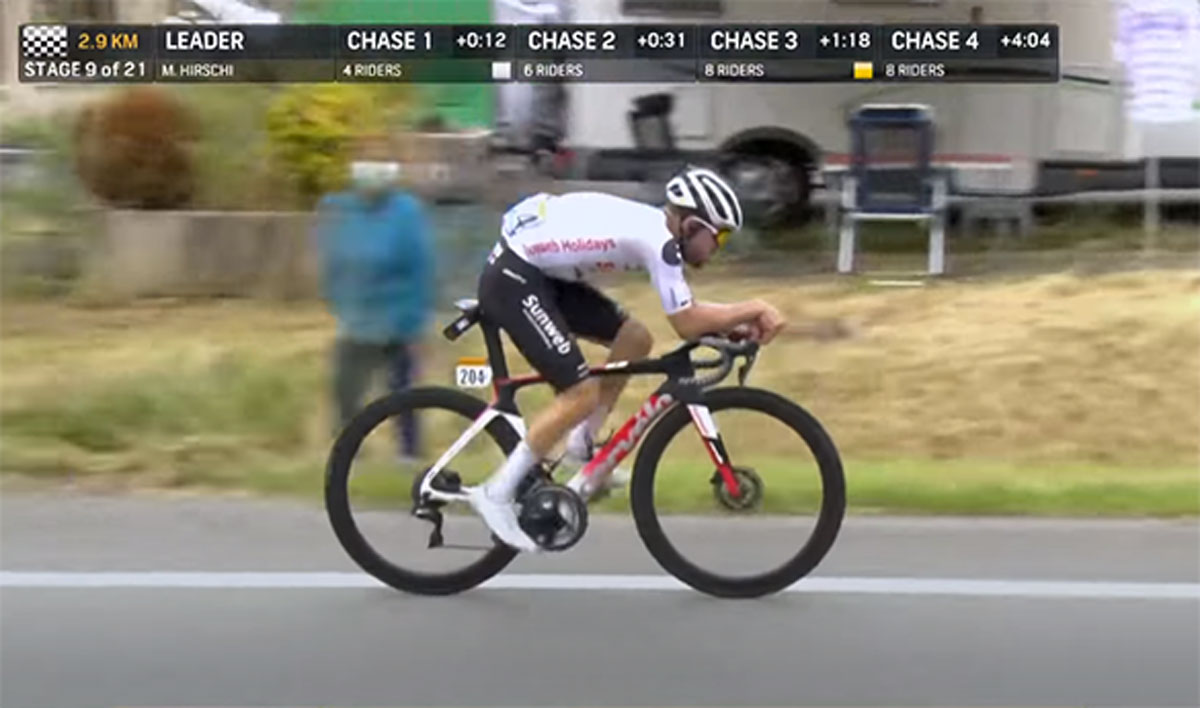

Not generally known to be any more outstanding of a descender than most GC riders, Froome stunned the chasers when he assumed the now famous “supertuck,” sitting on the top tube of his Pinarello and hunching down as low as he could get his chest over the bars while still gripping the drops – periodically pedaling in what appeared to be a comically inefficient position all the way to the finish, taking the win and the yellow jersey.

Since then, riders from the pro ranks to weekend warriors and KOM chasers have used the supertuck as an advantage to eek out every little bit of speed possible on their rides. Not only does the position seek to minimize the riders’ exposure to the wind and reduce drag, but the rider also reduces their slipstream and subsequently a chaser’s benefit to sitting on their wheel.

With its rise in popularity came the obvious scrutiny – plenty of us have been in a group ride where there’s that one rider supertucking as we cruise along at tempo for some reason, making the whole group question not only the reasoning behind its employ but also the riders’ ability to deal with the hazards of the road safely. This season, the UCI has banned outright the use of the supertuck in racing with a penalty of up to a 1,000 CHF (~$1,070 USD) and 25 UCI ranking points at world tour events, world championships, and the Olympics.

Not only has the supertuck seen its day, but also the forearms-on-the-flats TT style position favored by the Marc Hirshis of the peloton and other breakaway artists is now prohibited in road racing.

What does it all mean? Swiss-Side finds out

Cycling fans and aerodynamics experts Swiss-side have utilized their extensive resources to put together a study that quantifies the real-world impact of the UCI bans, putting some numbers down to help us understand how racing is likely to change without the riders able to cheat the wind in the supertuck or TT positions. With over 50 years of Formula 1 experience backing wind tunnel and CFD data on the two now-illegal rider positions, Swiss-side have come up with comparisons of the supertuck and TT positions versus the traditional riding positions that remain permitted by the UCI.

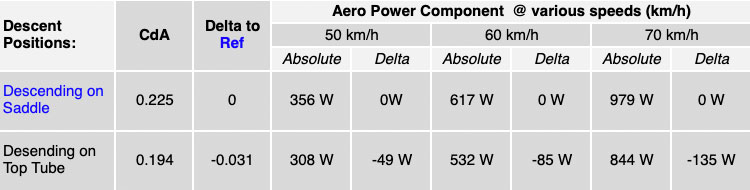

Supertuck

Swiss Side’s testing, based on an 8% descent revealed that “the Super-Tuck position sitting on the top tube will bring a 5km/h higher top speed and save 30 seconds per 10km of descent.” In road racing, where the winner is often decided by seconds, the advantage to a rider employing techniques like the supertuck to decrease their aerodynamic profile is huge.

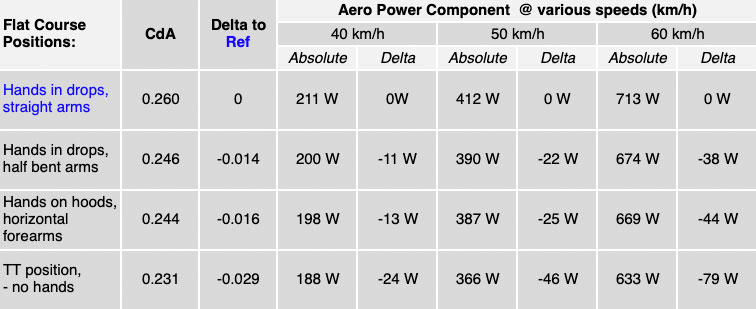

Road TT

Modelling around a 50-60km/h breakaway scenario, Swiss Side found that “the aero drag difference between the two most likely used positions, – drops with half bent arms, or the TT position, can be between 24W – 41W.” What that means to the breakaway rider is that over a 10km stretch, the additional drag induced by the next most aero (while still permitted by the UCI) position would reduce their advantage by 13 seconds or 180 meters given the same effort. Again, more than enough to win a race by and very much significant discrepancies.

Regardless of what you believe, it is certain that riders will seek out new ways to cheat the wind – with UCI regulations to follow. Swiss-side present a compelling opinion that “certainly there is an element of risk involved in riding either position, because the level of control on the bicycle is reduced. It could be argued that professional cycle racing is not just about the physical abilities of the riders but their technical skill and abilities to ride their bike. This certainly is the case in mountain bike and cyclocross racing, why should it be any different in road racing?” They claim that objectively, the UCI’s ban on the supertuck and TT positions will “increase aerodynamic drag and decrease speed” and assert that racing’s excitement and entertainment aspects will suffer as a result.

Is new equipment on the way?

It is certainly a challenge to balance regulations that keep riders safe and those that keep the playing field level, but any way you slice it the UCI’s ban on the supertuck and TT positions reduce the number of tools that teams have to employ in race tactics. Whether or not that’s a good thing is up to you – let us know your thoughts in the comments!