Editor’s Note: Chris Currie has been in the industry for years, many of which he’s spent quietly designing, patenting and slowly but surely developing his own full suspension platform. In this new series, he’ll give us a peek inside the process of creating something new, the myriad ways to bring it to market and the challenges of it all. Without further ado, here’s Chris:

Eighteen years ago, I started an online bike shop called Speedgoat out of an old one-room schoolhouse in the mountains of Southwestern PA. I didn’t have “start-up capital,” a background in web development, or a business degree. All I really had was an obsession with bikes and a wife who was just crazy enough to go along with me. For fourteen years we worked with the best companies in the bike business, building up thousands of custom bikes for riders around the world. We knew the names of our customers’ dogs, even if the customers lived thousands of miles away. It was that kind of business.

In 2010 I sold the company to people I thought could take it to the next level, but they were a trainwreck. Frustrated with the new owners, I left in 2011. In the years since, I moved west to manage sales, marketing, and customer service for Velotech in Portland, Oregon, while moonlighting for Stan’s NoTubes, where I’m now Creative Director. Through it all, one personal project that started at Speedgoat ten years ago has stayed with me. I had an idea for a bike.

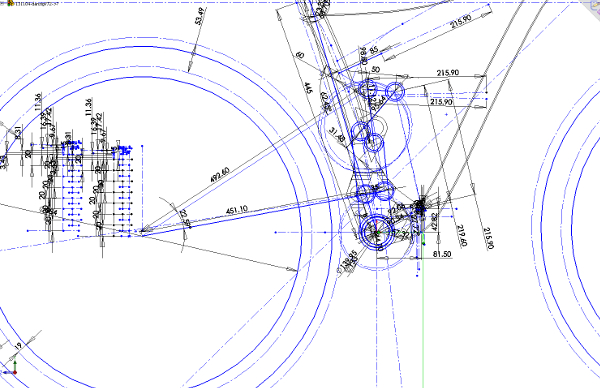

Since 2004, I’ve been quietly developing an entirely new suspension platform. The original idea started innocently enough, but got out of control pretty quickly. I ended up teaching myself Solidworks to be able to draw and dimension what I was trying to visualize in my head. I applied for a patent in 2007 when the numbers started telling me this could be something special, and was granted a patent for the design in 2010. Until you have a rolling prototype, you have nothing, so I didn’t make a big deal about any of this, but somehow the design started to earn a bit of an underground following among engineers and product managers. In 2011, I was in such a low place after leaving Speedgoat that I started writing about the design on a blog I’d started. A few early drawings made their way around the interwebs, and I started to hear from people in the industry. They were getting it. They could see what I was trying to do, and there were a lot of questions about licensing and what I was going to do next, some from people I respected very much. One day I sat down, re-read my own patent online, and started opening files I hadn’t touched since the whole company sale debacle. I had no idea how to make a proof-of-concept bike, but I knew that’s what I had to do.

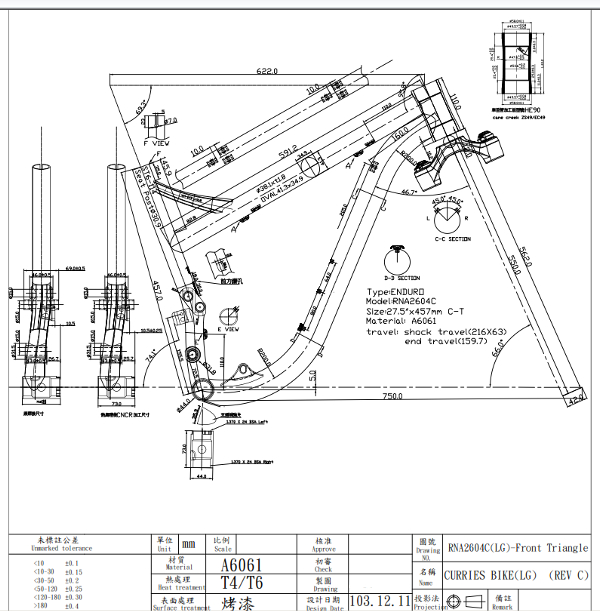

Today I have six of those bikes sitting in my garage (my wife is still extremely understanding). The current prototype has 160mm of rear travel (6.3″) and is built on 27.5″ wheels. It has a 66º head tube angle when used with a 160mm travel fork, but it’s designed around a straight 1.5″ head tube, so it accepts AngleSets and Works headsets with tapered forks, making the full HT angle range 64-68º. Seat tube angle is 74º. Axle path is one of the special things about the design, and it lets me keep the chainstays to 429mm (16.9″) with plenty of clearance for 2.4″ tires.

The bottom bracket height is adjustable with a chip system built into the lower shock mount, and the frame uses an 73mm English bottom bracket. I had an idea for a PF30 system that wouldn’t creak, but at some point it just didn’t make sense to deny the superiority of good ol’ English threaded bottom brackets (the worst part was admitting my friend, Jason, had been right from the start).

Dropouts are set for 142mm spacing but are modular, because there are no standards any more. Prepare to be boosted. The frame has a removable ISCG tab and can accommodate a front derailleur, if you really want to do something like that.

The current bike is really just a test bed for suspension technology, though. That’s my patent, and that’s what stands out to anyone who rides the bike. Back in 2005, I made an absurd wish list of performance criteria that included obvious things like chainstay length and axle path, but also more esoteric details about pivot point locations for manufacturing precision, leverage ratio adjustability, and shock placement (wasn’t allowed to mount in the center of the downtube, because I’m convinced that leads to really heavy, reinforced downtubes). I ended up designing the suspension to work with just about any shock orientation, though.

But one performance criteria set the tone for the whole system: The bike wasn’t allowed to bob at all on the climbs, even in a shock’s ‘descend’ mode. I mean no tiny pulse at the rocker, no subtle cable movement: zero. If you were under power, only bumps could make the suspension work. But -and this was the stupid “cake and eat it, too” part- you also had to be able to compress the suspension just by standing beside the bike and pressing down with one hand. I’ve ridden a lot of bikes that pedal great, but go jackhammer on you when you really need them to work. I’ve also ridden a lot of bikes that just don’t pedal well. Based on what I was seeing with instant center behavior and axle path on the computer, I thought this design had the potential to balance pedaling and suspension in a very different way. And it does.

I don’t come from an engineering background, but being stupid’s never stopped me before. I wasn’t a web developer when I created one of the first online custom bike configurators at Speedgoat, either. I’d be the first to say I have “fixation issues.” I have this natural gift for making my life completely unbearable. There’s probably a gene that keeps people from obsessing about ideas until they’ve stopped sleeping and wrecked their health. I don’t think I have that gene.

Back in 2005, the original business part of the idea was much simpler: develop a less expensive private-label bike as a compliment to Speedgoat’s high-end brands. The sensible thing to do would’ve been to pick up an open mold hardtail from Taiwan or China -just point to a picture in a catalog and move on to thinking about paint jobs- but I went down the rabbit hole. I’d been around to see some of the first suspension systems used on bicycles, and I’d spent so much time building and riding great bikes from Santa Cruz, Titus (and later Pivot), Niner, Intense, you name it, that I just couldn’t stop thinking about suspension systems. I’d work a fourteen-hour day at Speedgoat, then doodle pivot locations on pieces of scrap paper until the small hours of the morning. I started to see what really went into these designs, thought processes of brilliant guys like Joe Graney, Chris Cocalis, Dave Weagle, the ingenious ways Steve Domahidy and Chris Sugai were dealing with bottom-bracket drop issues on 29ers. One of the best things about trying to design something new was learning to really see what was already in front of me, the intent in other people’s designs. That’s when the insane wish list started.

In 2012, I started working with fabrication places both in the U.S. and Taiwan to create the current test mules. I worked with an engineer at Zen in Portland to make sure I had usable drawings and was accounting for all the components out there. After all, it’s nice to have cranksets that rotate and other basics. I hoped to keep fabrication in the U.S. because I thought that made more sense for prototypes, but Zen was really swamped, and no one had the time to take on the project, or even really estimate how many months it would be before they could. I ended up having to go to Taiwan, where I could get an estimated completion date.

Having a bicycle frame made in Taiwan is exactly like everyone thinks, and nothing at all like everyone thinks. The level of complication and overall expense actually went up in Taiwan -they’re not really into CNC machining one to two units- and communication becomes its own world with its own set of challenges. The problem with developing a product in Taiwan isn’t that they won’t build what you want; it’s that they will. Any detail you’ve missed, any problems with your design, get amplified and duplicated if you aren’t paying attention. I’ve invested in tooling and production for a dozen frames at this point. Any small detail that wasn’t caught and fixed with the first prototypes would now be wrong with those frames and the tooling needed to make them. Learning that process was both scary and amazing. If not for a key quality control guy over there, the whole thing would have been nearly impossible. It still seems impossible, but the first pre-production bikes are here and just about ready to meet the press and get test rides. At least one bike will be at Sea Otter.

What happens now?

I don’t know. I wanted to make a great bike, something different from everything that’s been done before. I think I might have actually pulled that off, but I’m still prepared for the whole project to just come to a stop. Then I guess I’m supposed to realize I’ve wasted too much time and money chasing this, except I’d do it all over again. Given the increasing level of interest in the system, it’s also possible the design won’t have been a waste of time. I went to Interbike and rode as many new bikes as I could this year, thinking I’d realize my bike wasn’t that special and I could come home and pull the plug on all this, but nothing I rode pedaled as well, and even some of the terrible pedaling bikes didn’t handle small bumps nearly as well. I’d never ridden some of the big brands before, and I was a little shocked at how bad some of them were. There’s definitely a reason lockouts are still around. It’s probably impossible to be objective when you’ve put this much of yourself into an idea, but I tend to be pretty critical of myself -the last five years alone were spent just refining the design until I was happy with even some pretty minor details- and there does seem to be something really good going on with this design. Every time I’m about to quit, knowing there’s something potentially great here pushes me one step further.

To figure out where this goes, I’ve once again taken over the Speedgoat.com domain name and am relaunching Speedgoat as a design shop for the new suspension system, and possibly as a small bike brand. I got burned pretty bad by the people who took over my company, but I fought to get the domain name back. There’s a good bit of interest in licensing the design right now, and Speedgoat.com will be where I offer information about the system. Beyond that, my current ‘market research plan’ is to show people the bike, let as many people ride it as possible, and see if anyone wants one. That plan’s probably not going to win any marketing awards, but I have to focus on my day job, and I don’t see any reason to bullshit people. I’ve made something I think works really well, but my means are limited, so it won’t be carbon fiber or have color-changing paint or anything. I’d like to get some feedback from people, keep refining, and see what happens. That all starts at Sea Otter.

But, we’re getting ahead of ourselves. In future posts, I’ll discuss what it takes to create and patent a new design, what I’ve learned along the way, why anyone would be crazy enough to try to do this, and where the project seems to be going. If you’ve ever been curious about developing your own bike or patenting a design, I’ll be happy to answer as many questions as I can in follow up articles. I don’t claim to be an expert at this, but I’m happy to share anything I know, and help anyone interested in doing your own thing. The press will finally get a good look at the bikes this Thursday at Sea Otter, but if you’re curious to find out more about the bike, you can sign up for news at Speedgoat.com. A little under two thousand people are already on the list, and I promised to share news and photos of the bike with them first.