Welcome to the Bikerumor First Aid Series, where we explore common cycling injuries and what to do if you or your riding partner wreck. Stories will provide in-depth solutions to help you get back to the trail head, recommended first aid equipment to carry with you, and more. If you have specific questions, leave them in the comments and we’ll answer those in future articles.

If you read the first installment in our First Aid Series you know the most common mountain bike crash injury results from a sharp blow to the head. As riders continue to push the performance envelope, concussions and other traumatic brain injuries are increasingly frequent—and more severe.

In the last few years, head injuries have dogged the enduro scene with a number of amateurs and top professionals sustaining multiple concussions. Some are now living with the debilitating fallout, which can be lifelong and worsening with time. To better understand bike crashes and brain injuries it’s important to know the basics of heads and helmets.

What are the most common brain injuries from cycling?

Bicycle helmets are designed to prevent injury to the scalp and skull—and absorb impact energy to protect against brain injury. According to helmets.org and a study done in 1999, bicycle helmets save as many as 88% of all crash victims from a brain injury. That’s a good score, but it helps to understand their sample set. That study would probably yield less positive results if it was a study limited to aggressive mountain bikers.

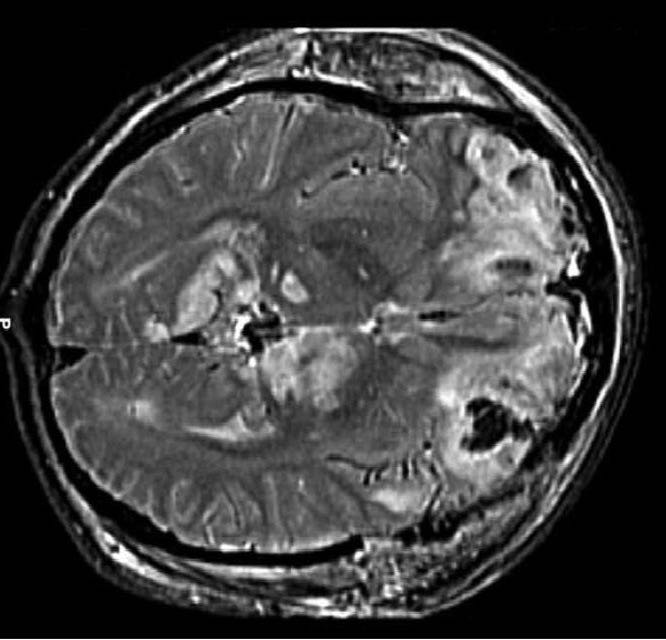

There are various types of brain injuries ranging from concussions and contusions to intracranial bleeding. Concussions are the most common to cycling and go by other names like mild traumatic brain injury. The exact mechanics behind a concussion are complex and not fully known. Some medical experts describe it as the abrupt jarring of the head that causes a large-scale and simultaneous misfire of brain cells. The electrical activity that follows damages nerve fibers and initiates a host of detrimental neurological events.

In heavy hits, the brain can rotate within the skull causing damage to brain tissue. It can also literally smash against the inside of the skull resulting in swelling and bleeding. New helmet advancements like MIPS, Leatt’s 360º Turbine Technology, and Kali’s LDL ArmourGel are designed to reduce those rotational forces and the trauma they cause. Doctors and experts agree these features don’t hurt, but they’re mixed on whether they provide real world advantages. It may not matter. Among high profile athletes who have either died from a brain injury or suffer daily from concussion induce disabilities, all wore a helmet.

What’s even scarier, a growing number of riders are experiencing prolonged symptoms of head injury without having suffered a substantial impact.

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

In the last few years, CTE has become a popular subject…mostly thanks to the NFL. It was even made into a movie starring Will Smith appropriately titled Concussion. CTE is a degenerative disorder caused by repeated impacts, not necessarily repeated concussions. Some riders who suffer the crippling effects of CTE don’t think they ever impacted their heads, but maybe just endured years of heavy jostles and shakes. If you think you are suffering the symptoms of CTE, you should get medical treatment immediately. The signs include memory loss, mild confusion, irritability, depression, mood swings, and alterations to your sense of smell, hearing, or even taste.

Crashes, head injury, and the first on scene

Here’s where I slip in a disclaimer. This is not a medical journal and I am not a doctor. The information provided here was vetted by a professional first responder, but should only be used as a general overview. It is intended to illuminate the seriousness of head injuries and encourage you to seek out professional first-responder instruction. With that…

Head injuries caused by bike crashes can be hard to spot. There is seldom any visible evidence beyond a damaged helmet, and the helmet may not appear damaged at all. Even if the victim is conscious, alert, and communicative, that doesn’t mean they’re okay. Symptoms of a concussion are subtle and can take minutes, hours, or days to manifest.

When assessing a crash victim with suspected head impact don’t rule out the possibility of a neck or spine injury. One of the normal symptoms of a concussion is a sore or stiff neck. Our noggins are relatively heavy compared to our weak necks, so the momentum of a fall is likely to strain or injure our delicate head pedestals. Don’t wait for the crashed rider to hint at such a pain, treat it as a neck and head injury.

The first order of business is to quickly assess for other injuries without removing the rider’s helmet. Only remove the helmet if it’s compromising breathing or must be removed for obvious reasons. Knowing what to look for in a head injury is the key. The various signs of brain trauma often, but not always, indicate the severity.

Typical signs of a brain injury are:

- Slight discombobulation, mild confusion, or change in behavior

- Pupils of unequal size or won’t dilate with light

- Nausea or vomiting

- Sleepiness or lethargic movements

- Blurred or spotty vision (Seeing stars)

- Ringing in the ears (Hence the phrase, rang your bell)

- Unusual behavior or emotional irritation

- Difficulty managing motor functions or unable to move limbs normally

- Momentary or prolonged unconsciousness

- Severe headache

- Poor balance

- Dizziness

- Repetitive speech

- Elevated sense of anxiousness

- Fluid or blood in the nose or ears

Without getting into the specifics of Level of Response (LOR) and determining a patient’s “orientation,” you should understand the basics of those assessments. If a rider can’t answer basic questions, that can help indicate the severity of the injury. Ask the rider what happened, what day it is, where they are, and…who they are. Any hesitation or failure to answer those questions is ample reason to suspect brain trauma. Time to call in a medical team.

Treatment on the trail

Unfortunately, there isn’t much you can do to treat a concussion or severe brain injury on the scene. What you can do is record vitals, maintain an airway, limit movement of the patient’s neck and spine, and continue to assess changes in symptoms.

For many cyclists in this situation, the immediate solution is to ring up a friend or ambulance. As we already discussed in our mountain bike series, where these accidents happen influences the response actions. Mountain bike crashes usually occur far from roadways with no easy options for extraction.

Each scenario and where it takes place will determine the next steps. Do you tend to the patient as best you can and walk out, or do you put things in motion to bring in the cavalry and a full medical extraction? If in doubt, call for help. The last thing you want is someone with a brain bleed and a broken neck walking to the car. Even a mild concussion is worthy of professional attention on the scene.

Resources and additional information

As we did in our previous installment of our First Aid Series, we enlisted the help of Flynn George of Backcountry Lifeline. In addition to teaching hands-on first aid courses for mountain bikers, he is well versed with the available tools to help riders hone their first responder skills.

With regard to head injuries, George recommended all riders at least read through the information provided by Medicine of Cycling. Their overview of head injuries is full of useful information. He also suggests reviewing the course materials and online classes provided by the Center for Disease Control. Their comprehensive overview of head injuries is worth the time to study in detail.

In a coming installment we’ll review communication methods backcountry riders can use to call in the advanced rescue teams when out of cell range.