It isn’t often that a company sets out to make their suspension product less adjustable. But when your rear shocks are known as some of the most adjustable on the market, less adjustability can actually be desirable, especially for shocks destined for sale on new bikes. Not only are ultra adjustable suspension components more intimidating for entry to intermediate level riders, they are usually more expensive as well which drives up the price for both the OEM and the consumer.

For all of these reasons, when Cane Creek went back to the drawing board to design the new C-Quent, they had OEMs specifically in mind. The shock is still extremely adjustable, just at the factory level rather than the consumer. This is more akin to what many suspension manufacturers offer on complete bikes – shocks with base tunes that are customized to work with a specific suspension platform. Key to the C-Quent’s design however, was that it had to retain the Twin-Tube damper technology that is the focal point of their other shocks. The result is a less expensive, lightweight shock that comes so close to the ride of a DB Inlines, that Cane Creek wagers most riders won’t be able to tell the difference…

Even though Cane Creek has been really pushing their suspension technology recently, their experience with the stuff actually dates back to the first days of RockShox. It was here in 1989 that the company started manufacturing the first RockShox forks, though their first Cane Creek branded suspension product didn’t come until later with the AD8 rear shock. From the years of ’91-92 the company transitioned from DiaCompe USA which they had been since 1974 to Cane Creek, finding inspiration for the name from the surrounding nature here in Fletcher, NC.

Likely most known for their threadless headset patent, the DiaCompe and Cane Creek headsets are the result of their work with John Rader who came up with the idea. Cane Creek still manufactures their high end 110 series headsets in Fletcher, but their threadless headset patent expired in 2010 after a long tenure with their first licenses sold to brands like Chris King and Tioga. From the early days as DiaCompe USA, the company knew they “could do more than just brakes,” and it’s that attitude which has led them to be so successful in vastly different products.

When it came to the C-Quent, it was all about reducing the amount of external adjustability but still offering a high level of performance that was equally durable. Cane Creek has had their share of difficulties with the DBinline which they don’t deny. In order to ensure more durability both out of future products like the C-Quent, and current products like the DBinline, Cane Creek recruited Jack Hedden from the medical field who was most recently a Quality Engineer at Flextronics to head up Cane Creek’s Quality Assurance department. Cane Creek mentions that since many of the new processes have been implemented by Hedden, the failure rate of DBinlines specifically has dropped substantially and the C-Quent is off to a great start.

Part of the changeover in process is an all new engineering wing headed up by Jim Morrison. We weren’t able to get many photos of the new wing thanks to a lot of new projects floating around, but the space was filled with high tech testing instruments including a state of the art shock dyno. Shocks aren’t just dyno’d in development though – every shock that leaves the Cane Creek factory gets individually dyno tested after being vacuum filled.

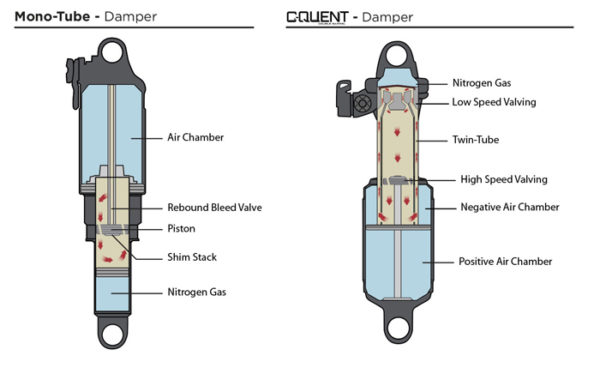

Compared to the DBinline, the C-Quent (shown in various prototype forms above) eliminates the tooled adjusters for low speed and high speed rebound and compression in favor of a single low speed rebound adjuster knob and the Climb switch. While the shock looks quite similar to the DBinline, Jim Morrison says that the project turned out to be very different than what they expected and resulted in them starting almost from a completely clean sheet. While the low speed damping is still housed in the valve body, the departure in the shock’s design came from high speed damping. Unlike their other shocks which use popets to control the high speed damping (shown being assembled by hand above), the C-Quent controls it through the piston with a shim stack. On the rebound side is a digressive shim stack with a cone shaped piston surface while the compression side features a similar digressive design but with more flow paths built into the head. Morrison says the design of this piston was really the key to making the shock work as well as it does without the external adjustments. However, the shocks can still be tuned internally through this shim stack adjustment (with OEMs having their own shim stack settings) and through a low speed adjuster that is set at the factory.

Which brings us to the ride. As it turns out, I stumbled onto a Cane Creek test session prior to my arrival in Fletcher. While down in Asheville for CX Nats, we ran into a large group of riders with hooded shocks out ripping laps at Dupont. It turns out that this was Cane Creek’s way of testing to see whether riders were able to tell the difference between the same bike set up with either a C-Quent or a DBinline. Not surprisingly, most riders apparently couldn’t differentiate the two.

I didn’t get the chance to ride the two back to back, but I did get a chance for some solid Asheville miles on a new BMC Speedfox 03 Trailcrew. The aluminum rig includes 150mm travel front and rear and was fitted with an OEM spec C-Quent rear shock and RockShox Pike up front.

With miles and miles of technical trail right out their front door, the surrounding area serves as the perfect test zone for Cane Creek’s suspension. Our day started with a steep, switchback strewn climb so we could sample the insanely fun 2.8 mile descent Kitsuma trail is known for. The trail is fast and it is strewn with roots, braking holes, and small ledges that you can drop or air. In other words, the perfect opportunity to see if your suspension is dialed.

On the way up, the Climb switch was used to the full extent as the brutal heat and humidity of the afternoon made me wish for more gears. The Climb switch doesn’t really act as a full lockout, but it did make the BMC Speedfox climb more efficiently. The lever is also not an on/off switch so you can position the lever anywhere in the travel and get more or less suspension taming ability. Even when forgetting to turn the Climb switch on, the bike still climbed fairly well though noticeably different. When the trail started to point down it was time to open it up – especially as I tried to follow Andrew Slowey down the mountain. Contrary to what his name might suggest, Andrew is not slow and it took everything I had to keep him in sight on a new-to-me trail.

To get even more time on the C-Quent, we waited until it got a bit cooler and then hit up Bent Creek for some bonus laps since I was camping at Powhatan Lake for the night. More climbing, and more fun descending down Green’s Lick.

In the end, the biggest takeaway for me was how much better the back of the bike seemed to be handling the terrain than the front. The C-Quent didn’t feel like a “budget” shock at all. Instead, it felt like one of the best tuned rear set-ups I’ve ridden. On one hand this shouldn’t be too surprising considering I was at the company’s headquarters and had them set the bike up to my liking, but on the other hand this is a stock C-Quent that will come on stock bikes. The RockShox Pike is no slouch of a fork, so for the C-Quent to outshine it, to me was quite surprising.

Provided that Cane Creek has solved their durability issues (which it looks like they have), the C-Quent should usher in a new level of performance for more affordable bikes everywhere. Which makes us very excited for the next products to spring from Cane Creek.