There are essentially two ideas in bicycle rear suspension right now, and that is designing the suspension to be kinematically correct and using a wide-open shock, or designing a suspension that is simpler or lighter, and uses a shock with valving, sensors or other methods of controlling the ride. For instance, Specialized with their Brain shocks, Trek with DCRV, Cannondale’s DYAD, and even electronically controlled shocks introduce the technology into the shock to control the ride, whereas DW-Link, VPP and Split Pivot work to keep the kinematics correct in the chassis, and then use a simpler shock.

Sometimes we see each of these ideas go to the extremes. Most typical consumer goods are a balance of manufacturability, appearance, performance and cost, and bicycles are no different. Lapierre’s electronic suspension takes shock control to a new level, and i-track appears to be the company that is taking chassis kinematics to that far end of the spectrum.

Check out the complicated, yet brilliantly engineered bikes, and their process, after the break…

One of the primary things that suspension designers talk about is anti-squat. Also known as anti-bob, it is a trait of the suspension to resist compression or extension as the mass transfers rearward during acceleration. It is not just a simple equation, as it changes throughout every bike as the overall frame geometry changes, since it involves series of lines through the drivetrain, suspension pivots, tire contact patches and center of mass of the rider, and then all the corresponding intersection points of those lines. The challenge of a suspension designer is making all of those lines and intersection points end up where you want them, but also make the bike look like a bike, so typically, there is a balance in there of the design and the appearance, as well as how the bike will work.

i-track seems to be working through their design process publically, which is pretty cool to see the versions as they work on their design. Interestingly, i-track seems to be focused on achieving some very specific kinematic traits, and taking the more difficult engineering way to get there, using rollers and guides that move with the suspension through it’s travel. This allows them to continue to alter one of the forces that affect anti-squat, which is the line of force that the chain torque follows. Other companies in the past have used rollers to change the angle in which the chain pulls on the suspension, but i-track is actually mounting this roller to a moving suspension part such as the swingarm or linkage, and it is actually moving throughout the travel of the bike.

i-track has made these first three prototypes from steel, in their shed in Australia. They don’t appear to be ready for production, and in fact they say they are going to keep prototyping, and are looking for a manufacturer that may want to use their design, instead of making it themselves.

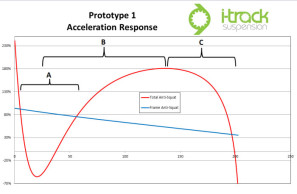

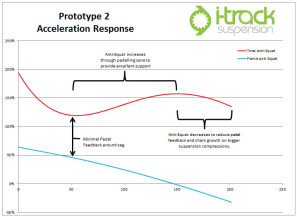

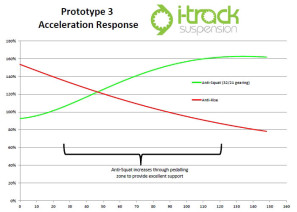

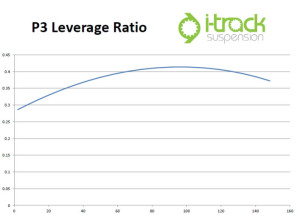

The guys at i-track even put all of the suspension rate curves and anti-squat curves of each prototype on their website. It is really interesting to peruse through and see the drastic differences in anti-squat that can be made in bikes that do not look too terribly different. This is where a lot of suspension designers try to start to protect their product, as its easy to make a bike “look” like another, but it may not ride anything like it. Some of the smarter suspension designers have not protected their actual design, but have protected specific methods to get to specific anti-squat lines.

What do you think? Is there a proper balance of working with existing parts and drivetrains, and making sacrifices to the suspension design? Or should suspension designers go to the extremes to make the suspension work, regardless of the special parts or complexity? Let us know in the comments!