Past attempts at mixed wheels have failed miserably so let’s break down why do it in the first place, where things went wrong, and how Mullet Cycles fared in their attempt at developing their purpose-built 79’ers(?).

Wheel sizes, like chain lubes & oval chainrings never fall short of creating a debate, especially when there have been repeated failures at attempts to say… use different sized wheels on a mountain bike. The motorcycle industry figured out decades ago the benefits of having a larger front, than rear wheel for riding on the dirt but it never caught on with bicycles despite multiple tries. Like the ill-fated 24/26″ wheeled Cannondale SM500 46er(?) in 1985 and later with attempts by Trek and a few other companies & frame builders with the short-lived 69er craze, nothing stuck.

While (still) having my doubts, I’ve changed my mind more than once on bicycle-related trends, (front suspension is heavy & slow, hard skinny tires are faster, underwear under bike shorts…). I had a rather long, nerdy chat with Mullet Cycles’s founders about their secret geometry, handling, this bike being the future, blah blah blah. I was transparent about my dislike for the previous attempts at different wheel sizes and they still seemed more excited than ever to send me their Honey Maker to shred.

Mullet History

Before I dive into the burger and fries on the Mullet Honey Maker, a little background information is worth mentioning. Mike Vidovich, the bike’s designer, raced motocross in the 70s & 80s, opened a motorcycle shop in 2013, and due to supplier issues, transformed it to Timberline Bicycles. There he carried several brands like Intense, Ibis, Turner, Ventana, and Foes which gave him an opportunity to become familiar with various suspension platforms. I’ll get into the tech goodness later but Mike knew how critical it was for a dirt bike to have different size wheels, and refused to accept a bicycle designed for similar conditions to not. He experimented by swapping 29er forks & wheels onto some of the various bikes he had in his shop thinking it had potential and the next thing you know, customers were buying into it. Mike now desired a purpose-built mixed wheel bike and reached out to some of his brands. One of his brands took interest and it took off… sorta.

As we were getting into the timeline, I mentioned doing a write up at Interbike in 2015 on a company doing what I saw as the first 27/29 mixed wheel attempts with full-suspension bikes. Mike chuckled and said “that was me. I paid for the booth, the bikes… everything”. Long story short, Mike said if he were to provide the geometry, pay for marketing, some up-front cash, and bought a large number of frames upfront, he would have exclusive rights to sell the model with mixed wheels out of Timberline Bicycles. According to Mike, things were doing great but just before he was about to hand over new geometry tweaks, the company pulled out of the agreement. Mike no longer carried any other brands and was unable to bring them or others in since he had liquidated his assets to invest in what was a short-lived effort. He had no other choice but to close Timberline Bikes.

As he was closing up shop, Miles Schwartz, owner of Miles Wide Industries, a small bicycle accessory supplier, stopped by to drop off some swag. Aside from an initial 3-way call, Miles has been my main point of contact. Miles is a mover & a shaker when it comes to ‘always be sellin’. Next to me, I am not sure I know anyone who could talk more about a product. He was however, very insistent I tell it like it is, probably not realizing, I already do that… often to a fault. On top of having an extensive cycling industry background, Miles was a downhill junkie having raced a few series in his past and has lived & ridden places like Pisgah and now his home of Colorado. Mike told him the story then gave Miles his personal bike and told him to turn on Strava. Miles came back having set some PRs & a KOM on his first ride and was hooked. Miles, being the savvy opportunist, and slinger of bike parts basically said, “We can do this” and Mullet cycles was born.

So enough of the mushy stuff, let’s dive into the tech behind this little mix up before we’re all drinking Bailey’s from a shoe.

Wheels throughout History

The bicycles you and I ride today are the continuing design of the ‘Safety Bike’. The safety bike was named so because, in comparison to the penny-farthing high-wheel bikes, the equal axle heights & same sized wheels reduced the chances of taking a header, (which is a saying that originated from going over the bars on a penny-farthing). Since then, the base design of a bicycle has changed very little over the last 150 years.

So, what’s the problem with past attempts to use different wheel sizes on bicycles if they are proven to work on a motorcycle? Simply put, a motorcycle weighing in at 250+ lbs and having a motor, that effortlessly puts out 200 times more power than any human ever could, mutes A LOT of the differences a person would experience on a human-powered bicycle weighing 25 to 30 lbs. For instance, the 29/26 combo was so far different in wheel size, a decent rider would feel the back wheel react a lot differently to an obstacle. I recall riding a 69er down a small 12-inch stepdown I’ve probably ridden a thousand times and going “nice…oof” as the front wheel made it feel great right before the rear slammed the trunk. It was also terrible trying to keep the wheel down on steep climbs.

For many years, I was never happy with 29ers on my local, twisty South East trails due to already being 6’1” and not chasing finish lines anymore. While faster, the taller axle height of a 29er didn’t pitch into turns as quickly back & forth regardless of geometry. I really just cared about ‘fun factor’ and in fact, my latest personal build is a slack, hardtail 27.5 bike with 150mm fork. Going from my bike to the 27.5/29 Mullet, also with a 150mm fork, I thought would be a great comparison. (spoiler, it was), I also did some things I was told NOT to do, [pffft] I’ll explain later.

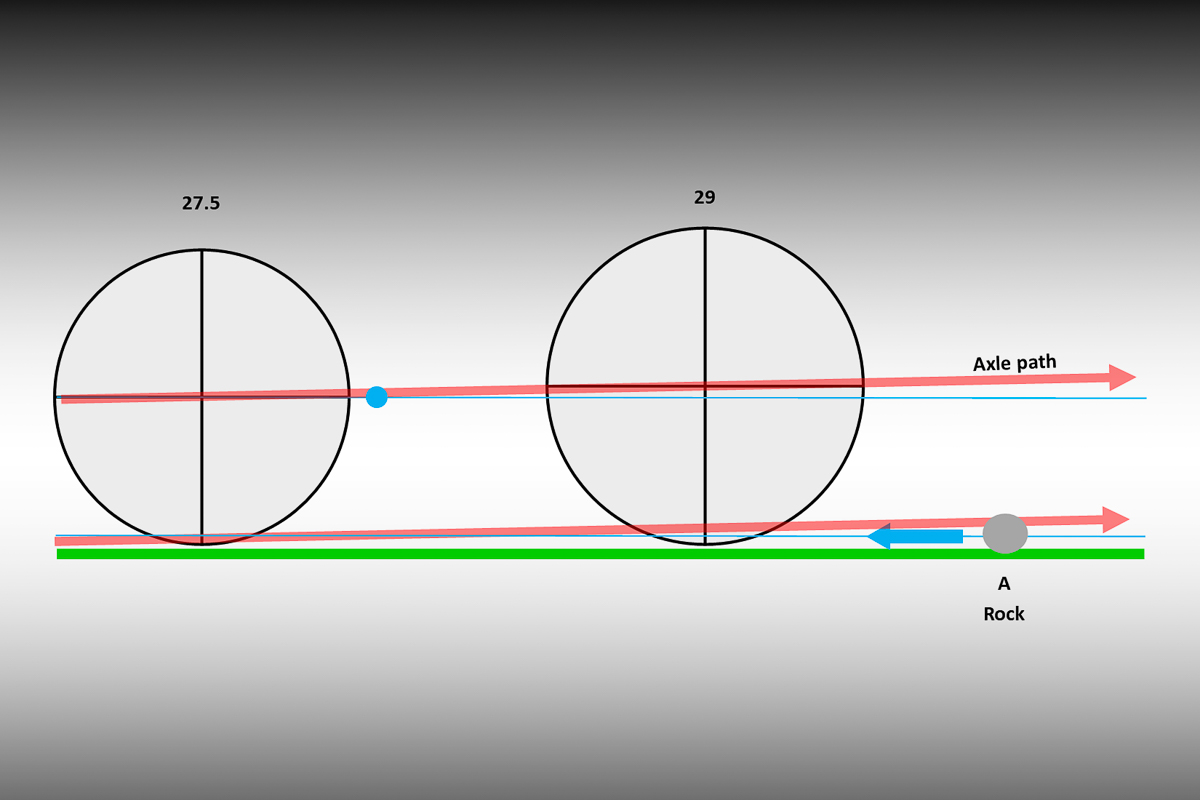

On a Plane

There are several reasons motorcycles, particularly dirt bikes, benefit from using different wheel sizes. One, while it does assist with snappier acceleration, the lower axle height in the rear assists the dirt bike’s ability to straighten up from being leaned over. Second, the slightly raised front end positions the rider more inside the motorcycle (I’ll explain this further down), rather than on top of it making the handling more intuitive on technical trails. Third, when a forward-moving bike whose tires are on the same plane (surface), the axle path has a rise to it, rear to front. (see illustration above). The axle on each wheel represents the two points of contact to the bike’s chassis. Because of this, the chassis has a rise which simulates a snow or water ski’s nose so any obstacle in the path will approach the slightly tipped up chassis in a similar effect to a rider lightly unweighting the front wheel over something.

On paper, the 27.5 does come a lot closer in size to the 29er… in fact, it’s so close, not one person that saw me on the bike even noticed the wheels were a different size. Part of that was probably because they weren’t looking too far past the sexy titanium frame… but still, I was surprised.

Prior to getting my dirty clean COVID-free hands on the bike, they insisted we have a conversation about what to look for, address a few common questions (like why their geometry chart is the way it is), and what not to do [double pffft]. While I have been primarily a mountain biker over the last 30 years, I have ridden motorcycles since the age of six and understood most of the ‘whys’ for different wheel sizes… and why they previously failed on bicycles. I also used to work for Maxxis and spent a lot of time working with tire design & testing so I speak the lingo when it comes to things like scrub angle front vs rear and predictive handling… two key things I’ll blab about further down).

Mixed Wheel Primer

Here’s a take on why dirt bikes work with mixed wheel sizes, past failed attempts with bicycles, and, what is supposed to make the Mullet different

Honda CR250 – 19”/21” Wheels

Benefits – Larger front wheel has a better angle of attack & more contact for better handling when pushed by the powerful rear wheel. The smaller rear wheel has a snappier response and more quickly flicks the motorcycle laterally upright during acceleration out of a turn. The different wheel sizes offer the rider a much more intuitive level of control in technical sections. Wheelies.

Drawbacks – You wear out rear tires faster. Wheelies.

Cannondale SM500 – 24/26” Wheels

Benefits – None

Drawbacks – Just imagine trying to ride over a log when that 24” rear wheel catches it. It snags trail obstacles like cargo shorts on drawer knobs. Trying to stand up on steep climbs would cause the rear wheel to spin out due to every little obstacle disrupting the entire contact patch and… well, the list goes on.

69ers – 26/29” Wheels

Benefits – Almost everyone I know who swore by the 69er setup ranted over its ability to roll over things better while having better acceleration. Some mentioned it would handle better as it made the rear more playful. I seriously considered one for a frame I was having built around 2007 but chose to stick to the more playful 26” wheels front & rear. (judge me all you want)

Drawbacks – Personally, I felt the difference between a 29” and 26” wheel was extremely noticeable. Having had a good amount of experience on dirt bikes, I really wanted to like it. Two key things swayed me back then. One was the geometry of those days did a poor job in making the wheels come close to working well together. Second, technical climbs were horrendous. Between the steep geometry and much higher front axle path, keeping the front wheel planted enough to turn was difficult.

Mullet – 27.5/29” Wheels & ‘Perfected Geometry’ *(these are their claims)

Benefits – Does what the 69er was supposed to do with better roll-over & acceleration, but with wheel sizes that are close enough to not disrupt the ride. Better handling at speed, in tight turns, and steep descents than both a 29er and 27.5 bikes due to improving chassis & tire scrub angle. Wheelies.

Drawbacks – You will have to buy 2 different tires. People won’t stop asking you questions.

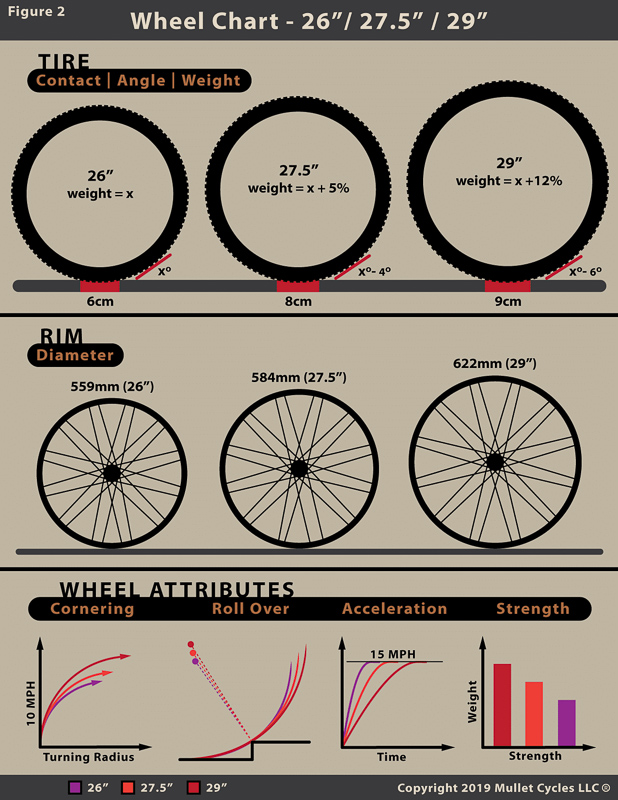

Often, what works on paper doesn’t translate well once the human factor is thrown in the mix, but it’s where you always have to begin. In the illustration above you can see a more accurate difference between the three wheel sizes. The key things to note here are how similar the contact patch is on the 27.5 & 29er wheels… while the turning radius of the 27.5 is closer to that of the 26” wheel. Now, I can’t verify the lower part of the above chart is accurate since I or one of my mad scientist, tire engineer friends didn’t create it, but it is more than enough to help everyone visualize what I’m about to talk about next. Scrub angles.

Scrub Radius?

During my time at Maxxis, I often snuck over to our tech center where tread patterns were born. Our engineers used a 3D printer well before they came mainstream to print sections of potential tires as it was critical in eliminating costly guesswork. Like kids in a sandbox, we would put these in various types of dirt add different sideways & approach angles to determine what was grabbing where… and what would grab next. This is where I learned about the importance of scrub angles and how they varied front to rear… especially when turning.

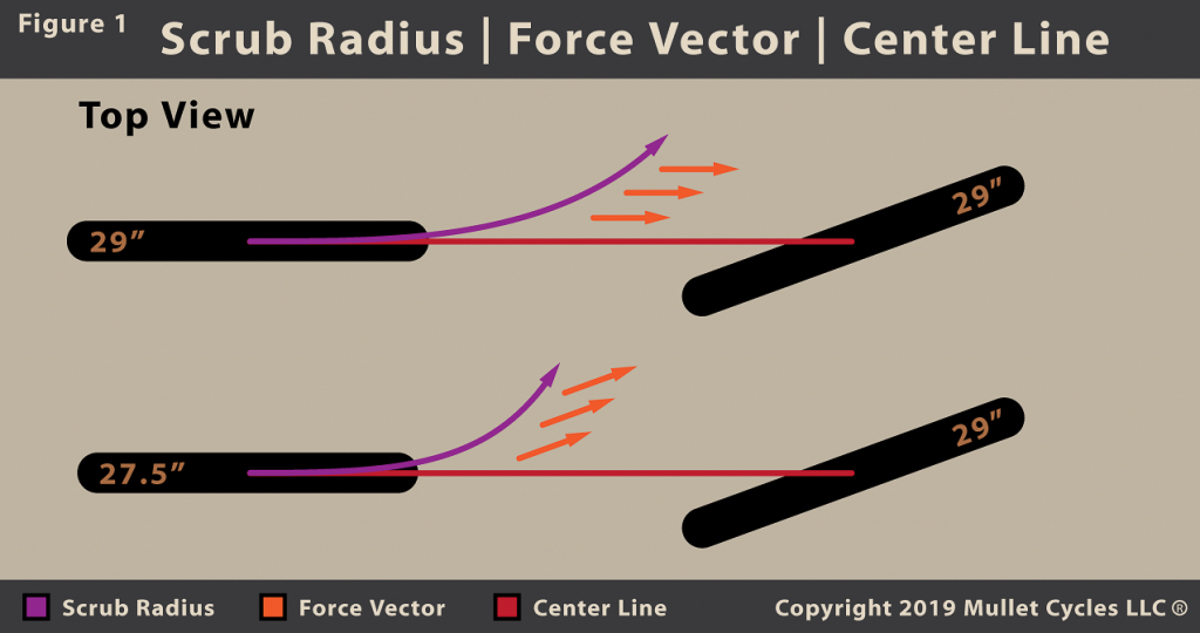

In the chart above, the top images represent two 29er wheels (or any equal size wheels for that matter), in motion. The lower images represent the two wheel sizes in question. What it doesn’t really show, but does represent in this illustration, is that the bikes are leaning inward during the turn. When a bike leans during a turn, the pivot point of the turn is based on the line between the two axles. When both wheels have the same pivot point (top images) and the front wheel is the only one that ‘turns’ the ‘fixed’ rear wheel sort of drags forward rather than along with the turn.

When you raise the front pivot point above the rear, leaning the bike becomes more intuitive requiring less steering input to turn the bike (this is a really big deal when on a 250 to 350 lb dirt bike in the woods). When the front pivot point is higher than the rear, during the lean, the rear tire’s scrub angle (remember, in motion) naturally faces more towards the turn as it’s happening, giving it a better chance of getting good traction and less chance of washing out.

An easy way to visualize the direction of force:

Take a pencil, laying flat on the desk and turn it as you push it forward as if to turn like the back wheel of a bike in motion going around a turn. It simulates a car drifting around a turn sideways. Now, take that same pencil and raise the front (pointed end) while doing the same motion as above. With the higher front pivot point, as the pencil turns, it’s pivoting on the eraser and turning more so with the front wheel.

Have I lost you yet?

Another aspect to the Mullet wheel combo, again on paper, is that since the chassis of the bike (where it attaches to the wheels), points up a bit, descending steep sections leans the angle of attack a bit more back… but climbing, it increases the chances of front wheel lift, (which was terrible on a 69er on steep and/or technical climbs). Mike and Miles swore they addressed this with the bike’s geometry so I was anxious to try this on a couple of hills I knew would challenge that.

Frame Details

So, let’s just stare at the bike for a second: Giant over-sized titanium tubing, elevated chainstays, sleek, eye-catching design, and 150mm of squish on a hardtail. With the 3” wide tires, this thing looks badfuckingass. The elevated chainstays are much more than looks though. It allows for a 3” wide tire (with room to spare), up to a 38t chainring, and offers a slight give to take the bite out. It also eliminates any potential chain slap.

The frame itself is in my opinion beautifully overbuilt as I am a sucker for titanium bikes, ovalized tubes, and old-school elevated chainstays. The downtube on the Honey Maker is massive, there are proper welds everywhere, and even added gussets in a couple of places for assurance. Because of the elevated chainstays, it looks more like a full-suspension at first glance since it does not follow the traditional hardtail’s diamond frame. They shipped the bike with 3-inch wide WTB Rangers but included a set of 2.4 WTBs to swap out upon my request. *(In the pics, the rear 2.4 had a sidewall puncture and I luckily had the exact tire in a blackwall, hence the different colored tires in some pics).

Oh, let’s not forget to mention the head badge cast in Sterling Silver by the same company who cast for Tiffany’s & Co. The rooster on is a nod to Mike Vidovich’s nickname for being a serial ‘rooster’ in his motocross days and the ‘drops’ are the blood, sweat, and tears it took Mike & Miles to get to this point. Given the amount of work & materials to build this frame, it’s $1,999 price for a frame is pretty darn good ($4,999 as tested)… if it works.

The frame has a low stand-over height and is designed to accept a 175mm dropper. Mike & Miles mentioned that because of the slightly raised chassis, the bike does well accepting forks between 120mm & 160mm (150mm tested), depending on how XC, Trail, or Enduro you wanted the bike to be. Their titanium frames sourced out of Asia, come with a 10-year warranty and their upcoming aluminum models (see below) will come with a 5-year warranty.

The frame has a low stand-over height and is designed to accept a 175mm dropper. Mike & Miles mentioned that because of the slightly raised chassis, the bike does well accepting forks between 120mm & 160mm (150mm tested), depending on how XC, Trail, or Enduro you wanted the bike to be. Their titanium frames sourced out of Asia, come with a 10-year warranty and their upcoming aluminum models (see below) will come with a 5-year warranty.

Bike Setup

Bike Setup

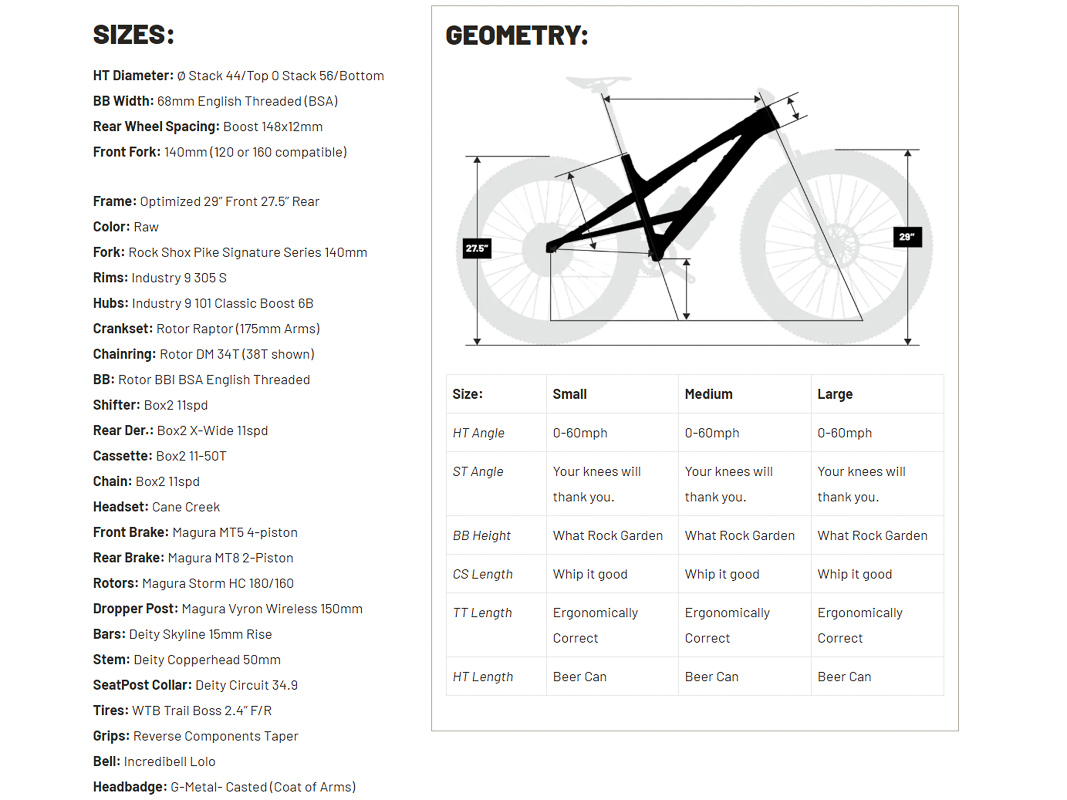

As you can see in their spec chart below, their geometry chart is a bit of a mystery. Rather than numbers, they put a little humor in each box. Their geometry is their secret sauce and they want to hold it close to their chest as long as they can. It might bother the head angle police, but in the end, once you ride it, you either like it or not. *(spoiler alert, I did!). Once I got the bike set up and stared at the 3-inch wide 29er wheel, I was ready to smash everything in sight. I really wanted to like the 3” tires as they look great on the bike but they squirm too much under my weight when properly inflated to roll over roots, etc. To get them to stop squirming, it feels like I’m riding on basketballs, (I run 2.6s on my personal hardtail hence why I requested the 2.4’s). Regardless, I ran both setups so no need to go into details on what tires to run other than this bike will let you run just about whatever you prefer. A couple of recommendations from Miles was to set saddle height, then get the bars as close to even as possible, and use the same tire, front & rear. He mentioned this because they found it really dials how the geometry works with the two different sized wheels. Being someone who usually scoffs at instructions, I (mostly) complied… which I’ll get into later.

As mentioned, the two wheels are so close in size, it is almost visually unnoticeable. Before the first pedal stroke, I wondered if I would notice anything at all… and whether that was a good or bad thing if I did not. A simple driveway road test didn’t push any of my buttons, good or bad. It just felt like a good hardtail mountain bike. Getting it out on the trails was no easy task as here in North Georgia, we had over 6 months of average rainfall in two… then COVID-19 hit along with a shelter in place. Despite the short time window, I was fortunate to get out on it as much as I did having access to a decent network of secret trails that never close just behind my house. My goto bike for local trails is a playful, 27.5 hardtail with 150mm fork so I immediately felt the benefit of the 29er wheel rolling over things better… and faster. Going over a chainring rubbing log was just as easy on this as it was my 27.5 bike with no major difference when the back wheel caught it… BUT, let’s back up.

Handling

One drawback to a standard 29er with a higher axle height (front & rear), is that it requires a tad more effort to get the front wheel off the ground. That has never been that big of a deal like it was in the early days of 29ers (long chainstays & taller axle heights made it wheelie terrible). The Honey Maker had that lower axle ‘snap’ I was used to and I later discovered, better than my 27.5 bike. In addition to the lower axle height, the slightly raised angle of the bike’s chassis appeared to aid in this maneuver. At this point, I have found two things I really liked, one of which I wasn’t considering until it happened.

My two biggest concerns were handling and climbing so let’s unpack those. Going into everything from a banked, slalom to technical garbage turns didn’t phase me one bit. I was really trying to nitpick the little things but it felt really natural… nothing like your typical 29er. The bike was fast & confident inspiring without losing that playful feel. I ride pretty light and often ride with little to no weight on the bars in technical sections. The Honey Maker made this easier to do because the bike had a more natural approach to obstacles due to the ever so slight upward angle of the bike’s chassis. I really felt a bit of my dirt bike muscle memory kicking in as I could let the bike track with less rider input (less leaning back) over obstacles & in turns. My body position stayed in a slightly more neutral position more often so I wasn’t having to dance all over the bike when going from a rock garden to a steep climb. This is where I began to appreciate the feedback and trust the bike more. Was it really that much better though? At this point, I wasn’t giving it any bad marks nor was I ready to give it any trophies… but keep reading.

Climbing

I have a few climbs that require manipulating a jumbly stream after a technical descent, maintaining momentum, and immediately sitting on the tip of the saddle to keep the front end down… assuming you have enough gas left in the tank to make it up a rather long punchy climb, (for perspective, my wife is that little dot on the other side). Since I have nothing to prove, 50% of the time I don’t even bother and push up the hill so I knew this would be a telling moment. The bigger wheel and raised chassis made it easier to conquer the technical stream thus keeping my momentum going almost every time. Once I began heading up, I could feel that teeter wanting to lift the front wheel up but it wasn’t bad. I did have to be careful though as when I did hit one of the many rocks or roots, it came up enough disabling my ability to steer, a second at a time. I think this could have been further improved had I swapped to a flatter bar, but the bottom line was, I made the climb more often because I nailed what is a very necessary good start.

But, is it better than my bike… and if it is, what happens if I just swap the fork and front wheel for a 29er on mine? Only one way to find out!!!

Back on the same wheel sizes…

One afternoon, my daughters wanted a dirt break during their sheltered homeschool day, so we mounted up and headed out. Not even a mile into the woods, I noticed my rear tire had lost some air. There was a small sidewall tear at the bead and climbing back to my house to swap out the Mullet for my bike seemed the better idea. I haven’t touched my bike in a month and when I did, wow. I felt a bit out of place… and I love my bike! The front end felt like someone added a 5lb weight to the front and I felt more front heavy. I also felt more on top of, rather than in, the bike. My bike felt twitchy and I frankly was a little WTAF. So I got back on the mullet after swapping out the rear tire and felt a preferred body positioning & feel. Well, damn.

Why not just add a 29″ wheel and fork to my current bike?

I got what I needed out of the bike so it was time to send back… but before I did, I swapped the fork and wheel to my bike to see if it was that simple or if the Mullet Honey Maker was actually something special. Once set up, I got on my DYI 79’er and hit the woods. Honestly, it wasn’t bad but I need to ride everything the Honey Maker excelled at before considering this to be a simple solution. In short, it didn’t not work, but it didn’t do it well enough. The biggest drawback was it wheelied waaay too much on climbs. (check out that seat angle!). The Honey Maker’s geometry was far more dialed, keeping it more planted. Descending was great since it pitched me back more as did the bike roll over things better, but the front end began to feel a little floppy as I slowed down for tight turns… especially when climbing.

Any negatives?

In the end, the only nitpick things I found worth mentioning were the front handlebar height & weight. The stem was slammed on the headset cup so the only adjustment I could have made would have been to swap out the bars. Second, was weight. I am not a weight weenie by any means but always weigh bikes for review purposes. We are programmed to think, if it’s titanium, it’s going to be light. The Honey Maker is overbuilt so it can handle a lot more than your typical XC racer and the build itself wasn’t light by any means as there was no carbon to be found and a RockShox Pike Ultimate upfront. All together the bike, (size Large, with the 2.4 tires), came in at 29.5 lbs.

Geometry… sort of

No, the geometry chart will make little sense. While tradition makes me want to know the numbers, a sort of blind test without knowing what to expect was kinda neat. From a consumer standpoint… well, above.

Availability

So how do you go about getting one? Is this the only bike they sell? What if you want something cheaper? Full suspension?

One interesting kicker, unless you live in a desolate area, Mullet cycles will only sell their bikes through a local bike shop. I am very fluent in the consumer marketplace, where the bike industry stands, and where it needs to go, so this threw me a bit… but in a refreshing way. They really want Mullet Cycles to enter the market through channels which can build their brand through person to person interaction & ride experience as well as build a little at a time without going too fast and it blowing up in their face. Currently, the Titanium Honey Maker is in stock and selling great.

Aluminum ahead?

In the pipeline, there will an aluminum Honey Maker, a full-suspension Peace Maker, and the Deal Maker… a MIXED WHEEL GRAVEL BIKE! The Aluminum Honey Maker will run $999/$2499 frame/complete, the hydro-formed aluminum (only) full-suspension Peace Maker will come in around $1,899/$3.999, as an optimized single pivot platform said to benefit from the mixed wheel size. The Deal Maker gravel bike will come in either Ti Single Speed, Ti Geared, and Steel Single Speed. Pre-orders for the new models start in June.

A little bit of me assumed I wasn’t going to like this bike or it be ‘neat’ at best, but Mike Vidovich’s work & experimentation, and Miles Schwartz’s shuffle & hustle have seemed to pay off.

Bike Setup

Bike Setup