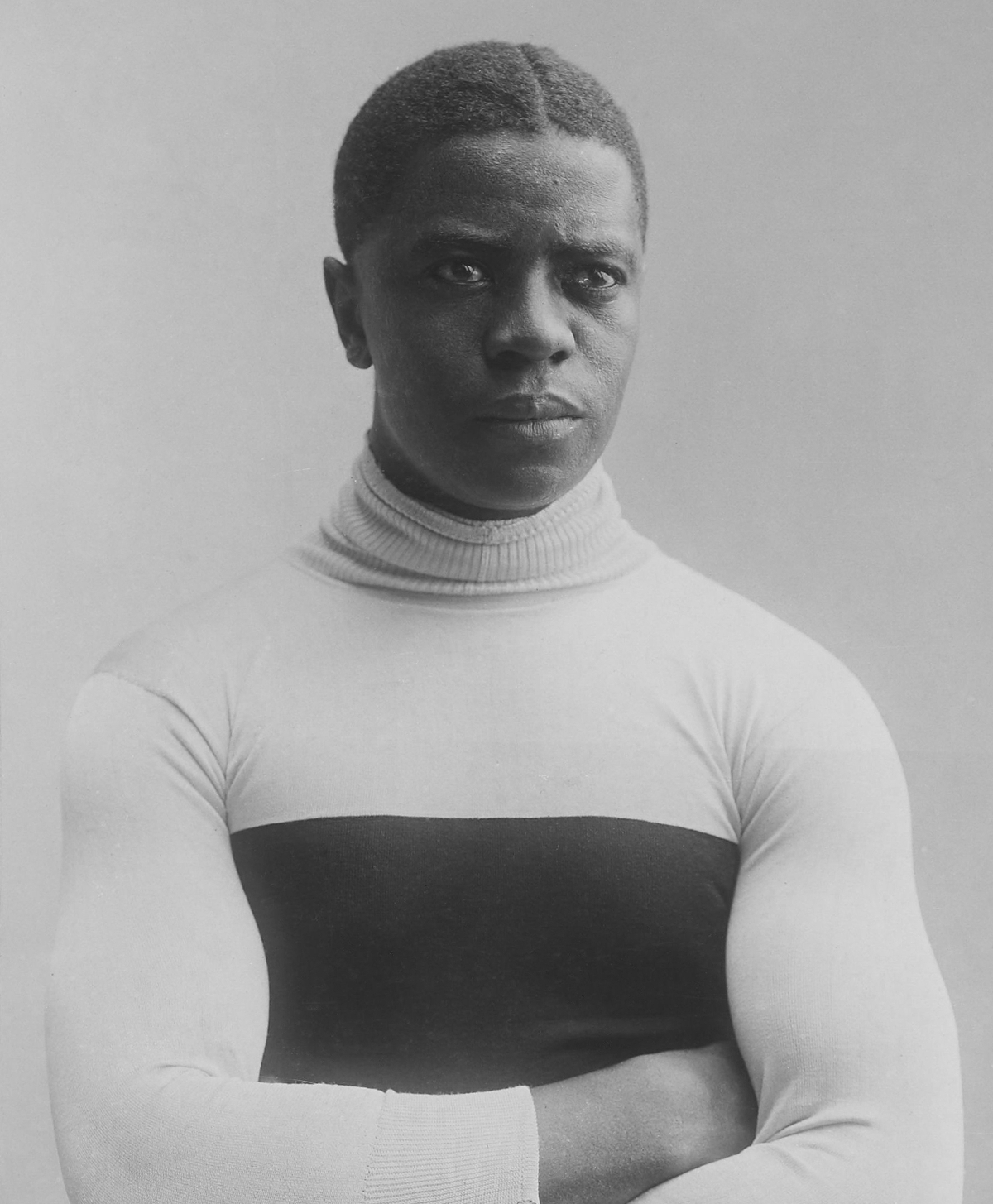

When 20-year-old Major Taylor won the 1-mile World Sprint Championship in 1899, he became the second Black athlete to win a world sports title. A year later, he successfully defended his crown.

Taylor’s first two world championships highlighted a dominant 17-year career in which he stood on hundreds of sprint race podiums. Along the way, he faced trenchant racism, stuck to his spiritual values, and collected hefty race fees throughout the United States, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

This March, his 1903 Peugeot race bike (wooden rims!) goes on display as part of an Indiana State Museum exhibit.

Becoming “Major” Taylor

Marshall “Major” Taylor started cycling as a young boy, with help from a wealthy white family who bought him his first bike. By the time he was a teenager, he’d become such a good trick rider that he landed his first professional gig. In the early 1890s, an Indianapolis bike shop owner hired him to pull stunts in front of his shop. Taylor earned $6 a week to clean the shop and do the tricks, plus a $35 bicycle — and a commanding nickname.

Suffice it to say he never looked back.

Only bantamweight boxer George Dixon had won another world sports title as a black man before Taylor’s 1899 sprint victory. Despite his youth and inexperience on the world stage, the Indianapolis, Ind. native took to the starting line as a veteran competitor.

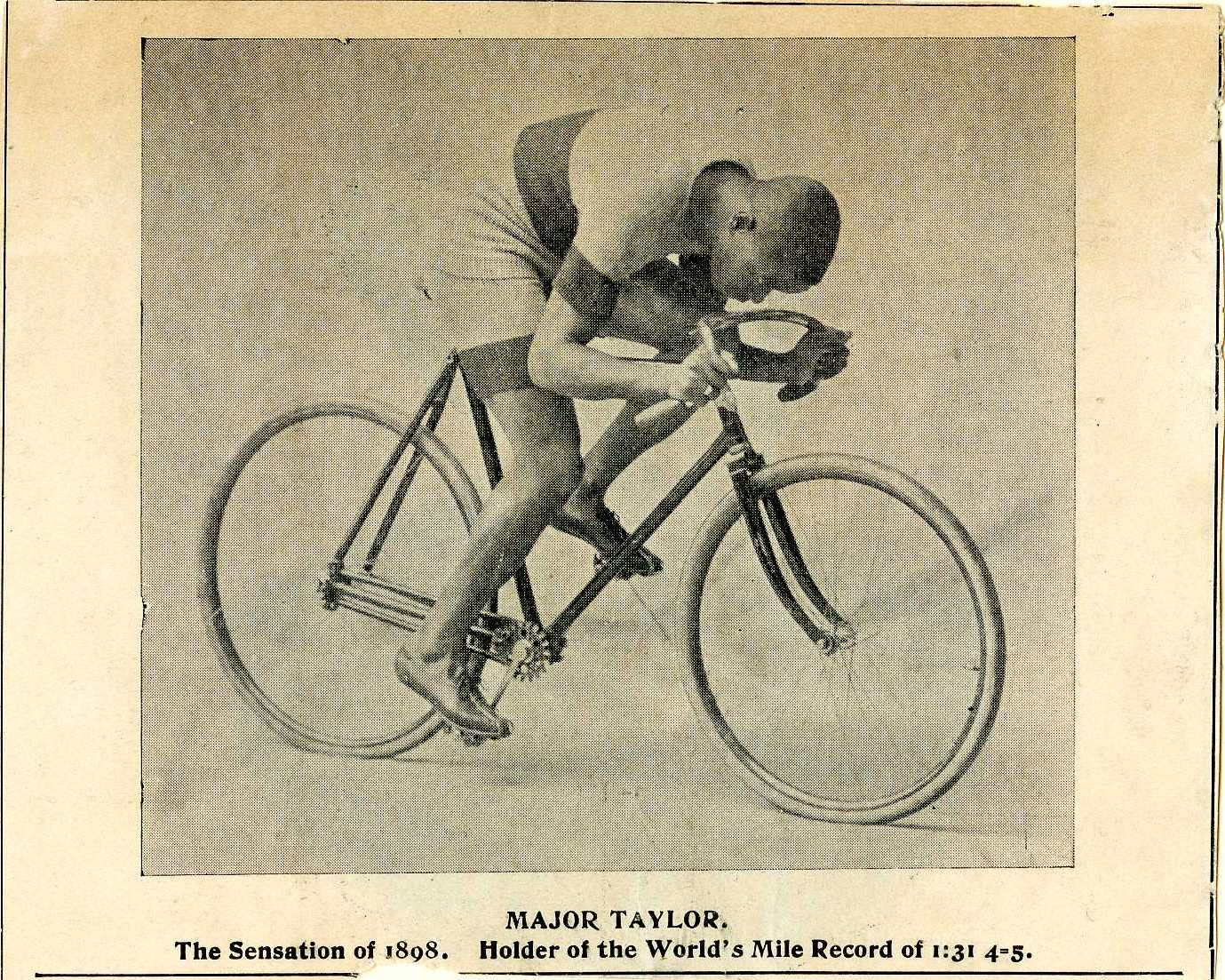

In 1898 alone, Taylor scored 29 wins, nine second-place finishes, and 11 thirds on the United States circuit. By then, he already owned seven world records, including the fastest time in a one-mile-paced match at 1:41 ⅖. He crossed the line a yawning 60 feet ahead of his opponent in the race.

His record one-mile time from a standing start, 1:41, stood for 28 years.

Facing down racism on an international stage

Taylor consistently rode in direct defiance of racism. To start his career, he moved from his Indianapolis home to Worcester, Mass. to get away from tracks that only allowed white riders.

In 1896, he entered a six-day race just after he turned pro. At the time, six-day riders still competed as individuals; cyclists commonly rode over 2,000 miles throughout the duration.

Riders who entered them at the time faced debilitating circumstances. Delusions from sleep deprivation, exhaustion, or possible drug use were common.

Taylor not only had it just as bad as every other athlete from a physiological perspective, but he also rode with a more-than-figurative target on his back.

At the 1896 six-day race at Madison Square Garden, Taylor withdrew on the fifth day. He cited sleep deprivation, but a reporter also wrote that he said, “I cannot go on with safety, for there is a man chasing me around the ring with a knife in his hand.”

The danger Taylor coped with could be administrative as well as violent. In late 1897, the professional circuit swung through the segregated south. There, race promoters refused to let him ride because he was Black. Taylor returned to Massachusetts, forced to watch Eddie Bald become the 1897 American sprint champion.

Taylor, however, refused to be denied and began to build momentum in the media. Before long, newspapers had given him various nicknames that spotlighted both his ability and his race. President Theodore Roosevelt became a fan, tracking Taylor throughout his career.

He also boldly traveled back to the south a year after promoters gave him the cold shoulder. While there, he received a handwritten death threat. He got it the day after he challenged three riders together to a race who had said they “didn’t pace [n-words].”

Taylor’s legend, and bank account, grow

Fans and media worldwide also came to know Taylor for his similarly staunch commitment to his Baptist faith. He commonly refused to compete on Sundays, which earned him suspensions in the U.S. and kept him from dominating the European circuit (where most races ran on Sundays).

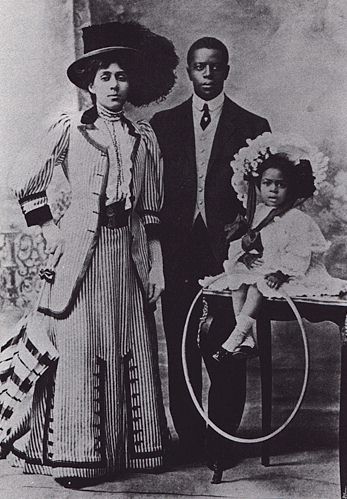

However, his spiritual devotion didn’t appear to cost him from a public relations standpoint — and monetary success followed. While he leveraged his generational talent to place in races despite white riders actively trying to injure him, his popularity helped fuel his finances. At the end of his racing career, when he was 32, his net worth totaled between $75,000-$100,000 ($2.2-$3.0 million in 2022 dollars).

However, Taylor’s career and life were grueling to the point that he broke down at times. He was cumulatively exhausted and took 2 1⁄2 years off cycling between 1904 and 1906. He came back to break more world records in 1907 but officially retired from competition in late 1909.

A champion in decline: retirement and last years

Taylor’s life in retirement proved challenging, too. He applied to Worcester Polytechnic Institute to study engineering, but the school denied him entry. He started businesses, but they didn’t perform well. He invested in other ventures, but the stock market crashed.

Still, he appeared to remain upbeat in his 1928 self-published autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds. In it, he said, “I felt I had my day, and a wonderful day it was too.” He said he held “no animosity toward any man” but did speak to his own set of ethics with what looks distinctly like a chip on his shoulder. “I always played the game fairly and tried my hardest,” Taylor wrote, “although I was not always given a square deal or anything like it.”

Taylor said that he wrote about the prejudice he faced to inspire fellow African American athletes. He admitted that the racism he experienced eventually burdened him enough, mentally and physically, to force him off the track.

Major Taylor died of a heart attack on June 21, 1932, after a few difficult years in Chicago, Ill. Partly because he’d become estranged from his family, no one claimed his remains and cemetery workers buried them in an unmarked grave. In 1948, former pro cyclists teamed up with Schwinn to exhume and rebury Taylor’s remains under a grave with a proper headstone.

Taylor’s plaque, at Mount Glenwood Cemetery in Thornton Township, Cook County, reads, “World’s champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way without hatred in his heart, an honest, courageous and God-fearing, clean-living gentlemanly athlete. A credit to his race who always gave out his best. Gone but not forgotten.”

The Major Taylor exhibit, featuring his 1903 Peugeot

This year, you can visit the Marshall “Major” Taylor exhibit from March 5 to October 23 at the Indiana State Museum in Indianapolis. The exhibit is free with paid museum admission and features his wooden-and-steel Peugeot track bike. The bike’s geometry indicates his signature low riding position. Unique at the time, he credited his success partly to the technique.

The exhibit also focuses on educating visitors about the pervasive racism Taylor faced and, by all rights, overcame.