Moots, headquarted in Steamboat Springs, CO, has been in this building for about 11 years now. Kent Eriksen founded the company in 1981, starting in the back of a bike shop before moving into a warehouse. Current owner Chris Miller came on a few years later. Eventually, as the company started growing faster and production demand ramped up, Eriksen split off to build his eponymous, custom bikes, and Miller took over full time.

From ’81 to ’91 they built only with steel, and only full custom. In ’83, they built their first mountain bike. It won the first NORBA Nationals under Steve Tilford, but it was badged as a Raleigh.

In 1991, it was a virtual overnight switch to titanium. Tubing quality became better and more diameters and sizes became available. That’s when they started developing stock sizing, too.

After about 21 years of renting, they decided to build their own factory and office. It’s 15,000 square feet, and the entire first floor is all production. Second floor has the showroom plus all the sales, marketing, admin and other desk work. On the third floor are three apartments – one for staff, one for guests (like us, thanks guys!) and one for the owners.

They offer tours MWF at 10am, but this tour is open 24/7…

In the showroom are a few desks, where Tammy (not shown, that’s our PR liaison Cathy in the foreground talking with Moot’s marketing man Jon Cariveau) processes all the web orders for parts and soft goods.

One of each model is represented here and showed a few updates that have taken place over the past 12 months. Moots’ carbon forks are now made by PMG, and are Moots’ own design. They had to switch when Alpha-Q stopped making forks. PMG is American owned, though they’re made in Asia, so communication was quick and easy, and they make a lot of carbon products for the top brands and bikes, so the quality is high.

They have 25 full time employees now, 18 of which are on the production floor. They pump out about 1,400 to 1,500 bikes a year, and about 15% of that is custom. They offer 8-10 stock sizes for road bikes, and around 8 for mountain bikes, so there’s plenty of sizes to avoid the custom up charge. That said, Cariveau says most go out with some options added like extra bosses, pump pegs, etc. The map above shows their North American dealer network.

Windows along a hallway at the back of the showroom look down on the machine shop and finishing area. The tube prep happens directly beneath it, and welding is on the front right corner.

TUBE CUTTING, MITERING & SHAPING

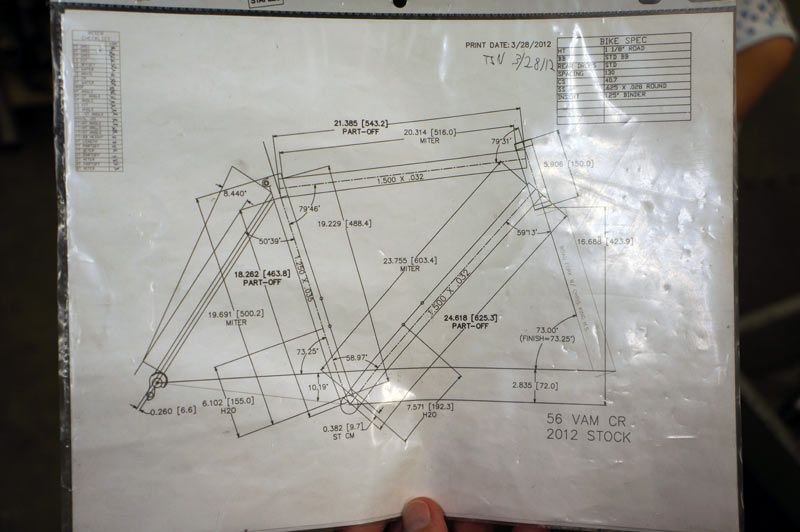

They have 31 different wall thicknesses and diameters to create the 16 different models of bike. Each one starts off as a set of measurements like this Vamoots CR road bike.

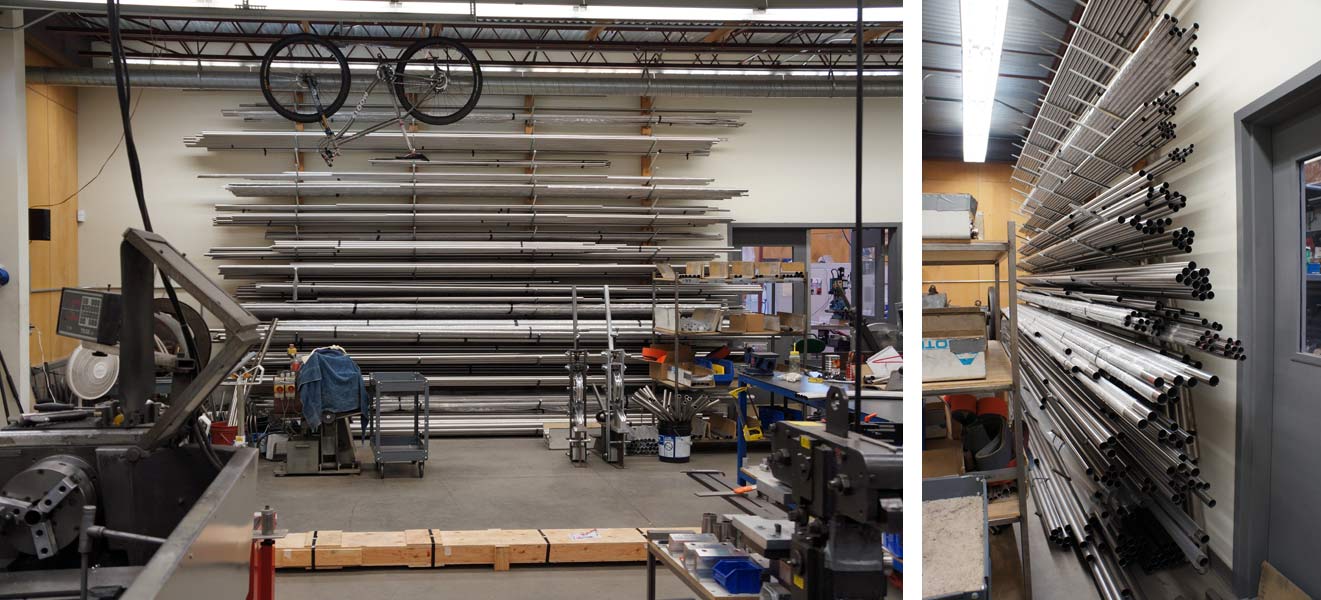

All if their tubing is US made, from Sandvik and Hanes. Cariveau says it’s the best quality. They’ve tested samples of foreign sourced tubing, and say it cracks as soon as they start trying to bend or shape it.

They use seamless 3/2.5, plus a bit of small diameter 6/4. It’s seamless drawn from a solid puck of titanium that has a mandrel pushed through it to make tubing. A 1.5″ diameter tube is about $28 per foot when it arrives on their door. The wider 1.64″ is far more, meaning a single downtube can easily be $150 worth of raw materials. They’ve used up to 1.75″ for custom orders.

Material costs are just one of the reasons Moots’ bikes are expensive. I asked Cariveau (with a warning that there’s really no way to sugarcoat this) why, compared to other custom titanium bicycle builders, are Moots’ bikes generally higher priced, even for stock sizing? Part of it is the overhead of a large operation, lots of employees and maintaining a dealer network. But the part I, as a rider and Moots owner, care about is the quality of materials and meticulous process. You don’t hear much about Moots’ frames having problems, and they come with a lifetime warranty.

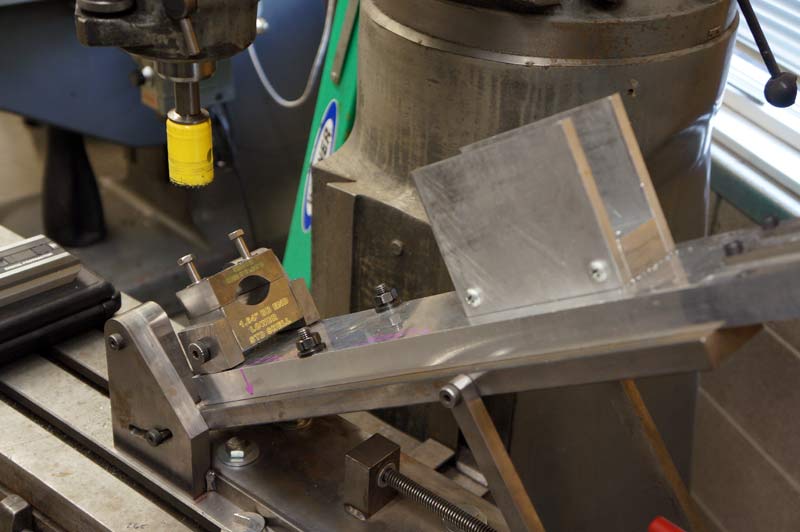

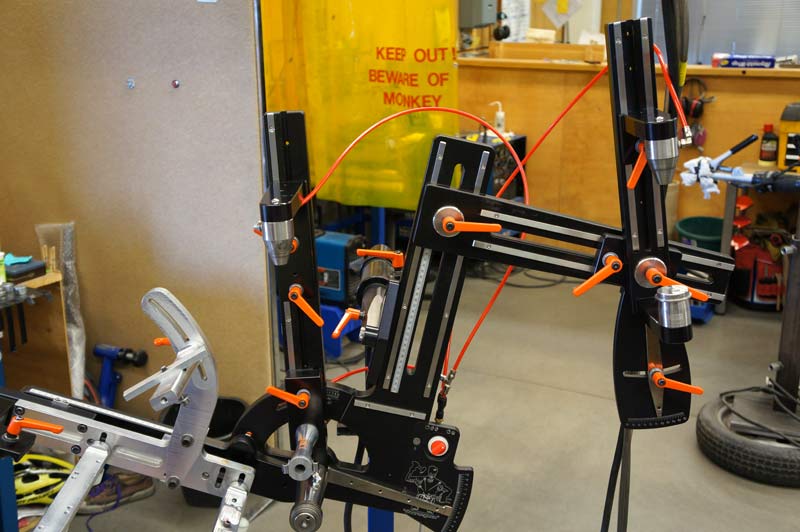

The mitering/cutting/shaping room is huge and full of machines. the reason for so many is that each one is dedicating to doing a certain type of tube and cut.

When they set up for a production run, they’ll batch orders and run a few extra to have on hand. Typically, for a bike like the Vamoots CR that’s one of their bread and butter items, they build twelve at a time per size, so the jigs are all set and they can streamline operations and make them all the same.

That combination of abundant machinery and processes allows for accurate repeatability and consistency, something that helps set them apart from smaller builders doing one or two bikes at a time.

They machine their own fixtures in house, too. All materials are cold worked. Anytime you heat metal, it weakens, so all of the tube bending is done at room temperature.

Frames all use size specific tubing, so smaller people/bikes get smaller diameter tubing.

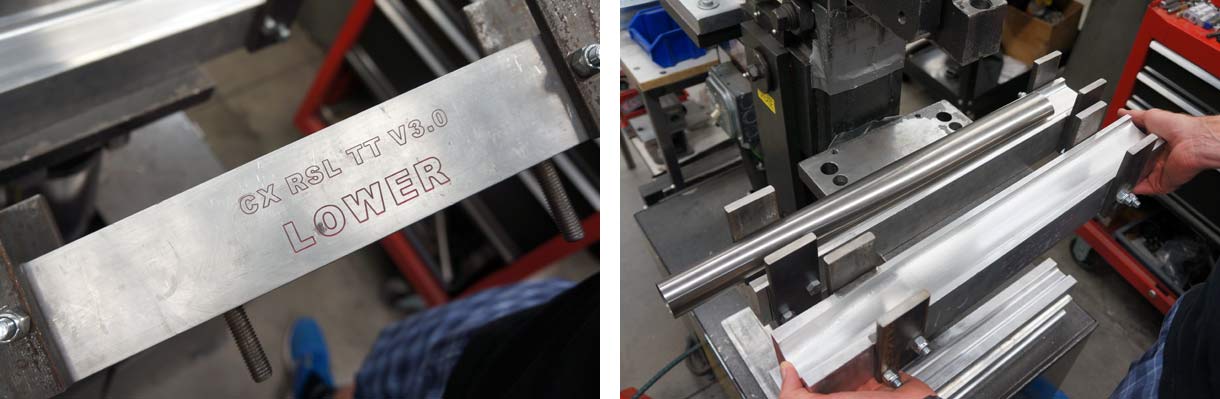

To shape the tube profiles (ovalization, for instance), a tube is set in a clamp with the desired shape. Sometimes it’s a small clamp like the one above…

…and sometimes it resembles a full length mold when compound or lengthier shaping is required. This one flattens and ovalizes the top tube on the Psychlo-X RSL cyclocross bike to make for easier shouldering.

Sometimes a tube can be bent and shaped in the middle, then cut to create two usable tubes.

For the precision of their mitering machines, some cuts are still done by hand.

Some of the subassemblies are tacked and prepped to go with the cut tubes, then they’re all sent across the hall to the welding room. But first, a quick detour.

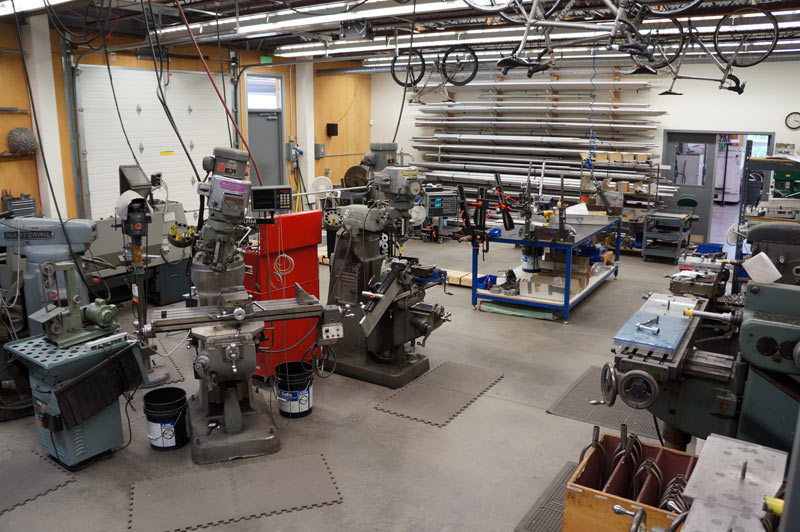

THE MACHINE SHOP

Four CNC machines make about 75% of the small parts (BB shells, headtubes, disk brake mounts, bottle bosses, cable stops, etc), plus the tooling for their mitering machines and benders.

Paragon Machine Works does the rest. Having them in house has really helped them speed up delivery time. It also lets them prototype faster.

WELDING

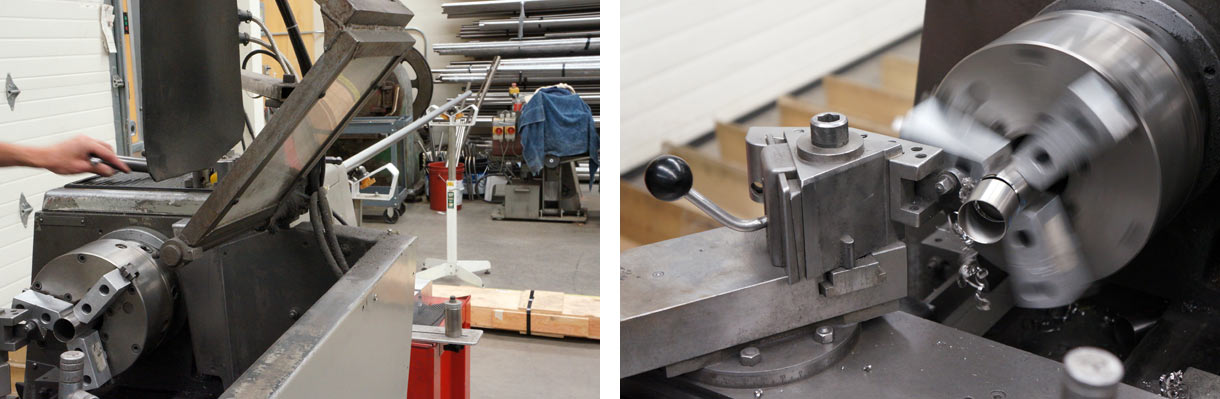

After the mitering room, tubes go to the welding room.

Tubes are grouped by model and size first.

Then they’re boxed into groups for a complete build…

The sections that will welded are brushed clean, then they’re put into into a hot soapy water mix inside an ultrasonic cleaner. This removes all cutting fluids, oils and fingerprints from the tubes. Without this step, the welds could deteriorate over time and cause a failure. They go from the wash basket to a dry basket, and from here on out they’re handled with gloves.

Clean parts are put into a jig and sealed for argon gas filling. They use tig welding, so the welding torch flows argon gas over the. Outside of the tubes, and argon is pumped through the frame’s tubes, to remove all the oxygen from the welding surface. It takes about 20 minutes to purge the oxygen from the frame before they can start welding.

They go through a lot of argon. Just disregard that Raleigh box.

They have six full time welders. Mark Rasmussen is the head welder. He and Bryce Davies tack all the frames, check for alignment, then they move through to be fully welded.

Before they’re tacked, the jig’s measurements and angles are double checked with a digital angle finder. It’s tacked with only heat, then moves on to one of the welders.

They use a double pass welding method. This means they do a first pass with only the torch, which essentially fuses the tubes together by melting the material into one. Then, they do a second pass with 6/4 rod. It usually takes about 2.5 to 3 hours to completely weld a frame, up to 4 hours if there are a lot of extras like third bottle bosses, rack and fender mounts, etc.

The precise mitering means less welding time and filler material is used, which makes for a stronger frame. They also weld in a very specific order and direction, which reduces warping from the heat.

Most of their welders were self taught and learned at Moots. One, Amy Decastro, started out in customer service but wanted to learn to weld. She went though UBI’s welding course and now does all of their subassemblies, stems and seatposts, along with a few frames.

FRAME FINISHING

In the back is the hand finishing area. That’s where the bottom bracket and headtube are reamed, chased and faced.

They get a final alignment check, hand checks over the stops to check for burrs, and the headtube is drilled and tapped for the badge.

Frames are bead blasted and waxed before they leave, which is their trademark finish. Cariveau says when you polish or brush it, it creates titanium dust, which isn’t very healthy to breathe, and it won’t look as good for as long.

Blasting it also means they can easily refinish it, which they’ll do for $350 and include an alignment check and fresh decals. Basically it’ll look like new.

After blasting, decals are hand applied, then the frames are waxed. They used to use Lemon Pledge, until Johnson & Johnson changed the formula. That threw them for quite a loop when the finish wasn’t turning out like they were used to. Now they stockpile this:

For complete bikes, this is the final stop for assembly.

Bikes and frames then get a smattering of other quality checks before they’re boxed up. Each one ships with a tag that shows who handled each part of the construction, any requested options and other notes.

RANDOM BIKES & PARTS

They can also do frame repairs. This one had a new derailleur hanger welded on.

Two classics: Moots’ no longer available TT/Triathlon bike and an original steel bike.

This frame had been converted into a dual single speed backcountry adventure bike. A 29er rear wheel with fat tire front combines the benefits of both where needed, and drop bars make for more hand positions over the long haul.

Two setups keep the ease of singlespeed with a bit more versatility. Easy gear for climbing and technical sections, big gear for hammering gravel roads.

The lower pivot for the MX Divide full suspension mountain bike.

Huge thanks to Cathy, Jon and the rest of the crew at Moots for their time and hospitality!