Along Denver, Colorado’s Cherry Creek Path about halfway between the massive flagship REI store and the Cherry Creek Reservoir recreation area sits Alchemy Bicycles’ headquarters. It’s a convenient location in that the reservoir is where weekly crits and TT events are, plus a bit of jumpy singletrack, and they’re a perfect warm up distance away.

The location houses the Nie Brothers Bike Shop, with siblings coming from University Bicycles and Colorado Multisport. You can see them in action building the bike for C-Bear’s Interbike build off in this video. Around the back is a branch office for the Pro’s Closet, and up front may eventually house a small coffee shop within the showroom.

Right smack in the middle of it all is where Alchemy cuts their own molds, manufacturers their own carbon tubes and lays together some of the best looking carbon bikes out there. Come on in and see how it’s done…

As you first walk in, their showroom greets you with current models and past award winners.

Mosey through and you’ll walk through a small meeting room where the coffee will (hopefully) someday be flowing regularly. Keep shuffling and you’ll head down a small hallway toward the fit room:

They use the Retul system and can fit customers here whether they’re buying a bike here or back at their local shop, wherever that shop may be.

They have a wide open manufacturing room with their own CNC machine to create their own molds. They’re now making all of their own shaped carbon fiber tubes except the round tubes, which are still made by ENVE. The plan is to acquire a round press and mandrel so they can make those, too, giving them a completely house made frame. They make stock sizes and full custom, but everything’s still made to order. They will eventually have some inventory of stock frames, and then add compete bikes further down the road.

Looking from the other direction. See that corner way back there, under the stairs?

That’s founder Matt Maczuzak’s “office”. It’s where the magic starts with one of these:

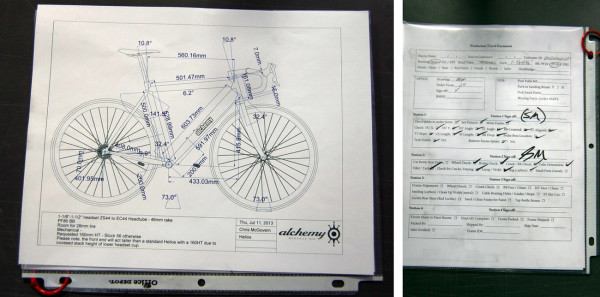

Based on the fit data and rider preferences, Matt draws up a spec sheet showing all the angles and measurements. Even things like whether the customer will use a straight or set back seat post are considered. Then, on the right, a checklist follows the frame through production to make sure all steps are completed.

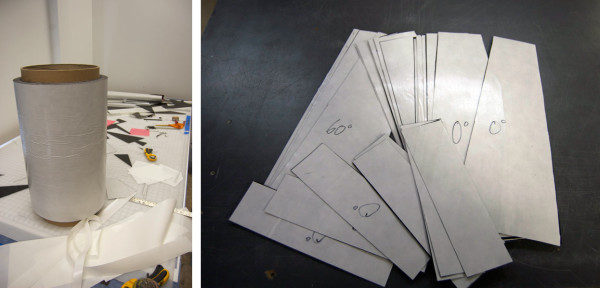

The tubes are all made with UD carbon. The pieces are cut with the fibers oriented in varying directions to provide the strength, stiffness (torsional, lateral, etc.) and compliance necessary. The numbers on the backing indicate the angle of the fibers so they know which order to wrap them around silicone molds.

Notice we’re not showing the silicone molds…that’s top secret.

One of the nice things about their full custom bikes is that even the bottom brackets can be any standard you want.

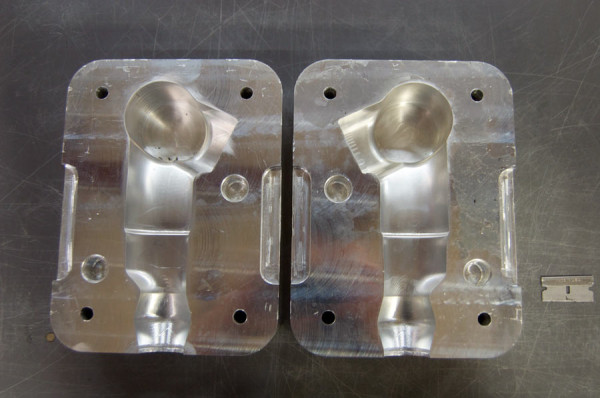

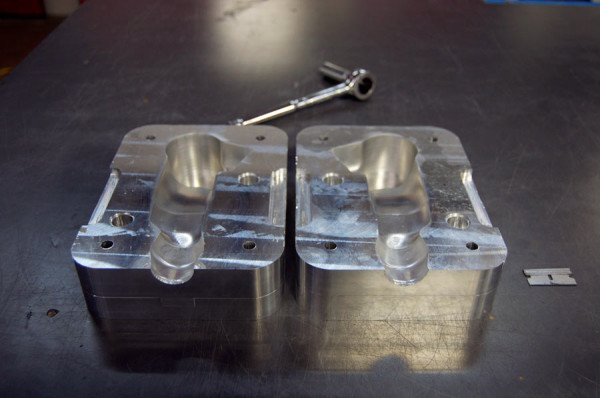

Each mold is cut in two halves. Once the carbon’s laid up around the bladder, it’s placed inside and the halves are bolted together.

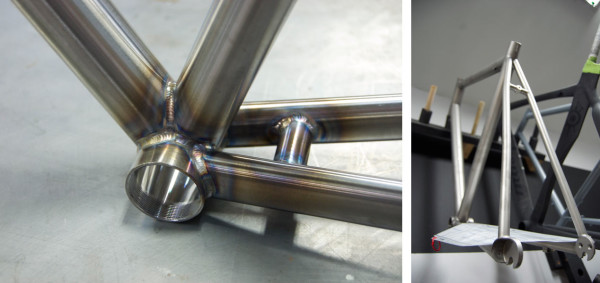

Headtubes are created using an internal alloy mold that is adjustable by using different spacers in the middle. Different end caps also let them directly mold different headset bearing standards. The result is a full carbon headtube that bearings drop directly into. The interior finish is so smooth we had to ask if they were alloy inserts to be sure.

The molds are cut from alloy, not steel, because it’s faster to cut, and they can do it in house. Steel molds would have to be outsourced. This also means they can make a custom mold quickly to make a new angle or size. Or prototype new designs.

The molds are bolted together and air is pumped into the bladders to press the carbon into the outside mold. That pressure, along with the heat from this press, cures the layers into a single tube or piece over a period of about three hours at around 350°.

The SmartPress is huge, but their molds are pretty small since they’re only molding single tubes at a time, not an entire monocoque frame. This lets them press several molds at once and be a bit more efficient.

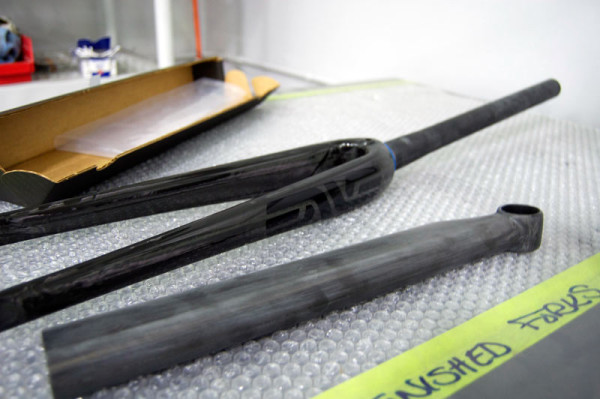

They’re now making their own solid dropouts, too, and those are done with chopped 3K woven carbon. That provides strength in all directions and better impact resistance than UD would. Unfortunately, showing the layup process would expose you to their silicone molds, so we don’t have any pics of that. Well, that, and they weren’t actually laying up a frame when we were there. But we can show you the finished parts:

With custom bikes, layup is controlled to tune the ride characteristics for the type of rider and what type of riding they’ll be doing. For example, a dirt road bike would have a more compliant rear end with less wrap at the chainstay/BB junction and dropouts, and keep the wrap from extending as far back on the top and downtubes. And those wraps are finished in a very aesthetically pleasing design, something that’s a bit unique. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

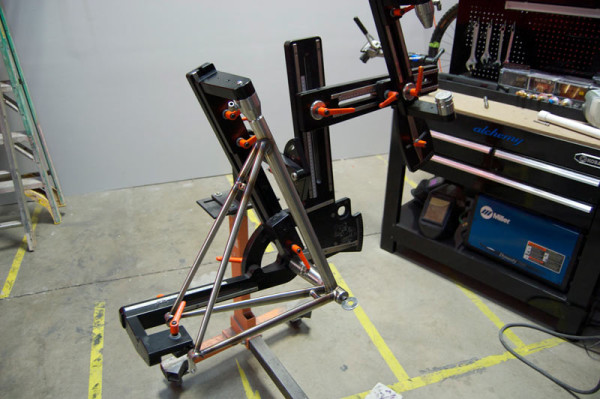

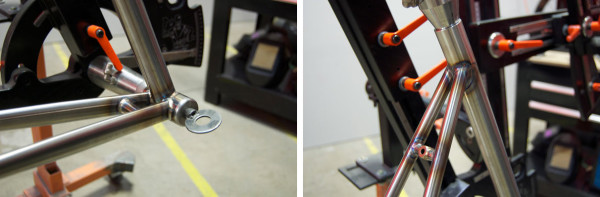

Once the tubes are removed from the molds, the parting lines (aka “flashing”) are cleaned up. Each piece is then mitered to fit together and assembled in a jig.

Once everything’s fitted and set at the appropriate angles, they’re lightly tacked together with epoxy.

Then they’re baked for 15 minutes to set things in place and the frame is ready to be wrapped with the outer layers of carbon.

Sam Maczuzak, Matt’s brother, handles a lot of the frame layup duties. He says the frames are strong enough to ride after tacking, but the wraps provide the security needed to handle real world riding.

Once the lugs are wrapped with carbon and everything’s checked for alignment, it’s put in a giant vacuum bag to compress the wraps around the frame and squeeze out any air and excess resin. Sam wraps joints as tight as he can, but the extra vacuum compression, upwards of 300psi, plus the heat of the oven, melts the resin so all the layers of carbon essentially fuse into a solid structure. He says carbon fiber is strongest under tension, and the compression creates tension in all the different layup directions. The frame sits in the compressed state for three hours in the oven to fully cure.

Beyond the proprietary tube shapes, what really sets Alchemy’s bikes apart visually is the complex layers of carbon at the joints. Fortunately, that outer “cosmetic” layer is still 100% functional. It’s done to ensure that layer termination is evenly spread throughout the joint, to taper the joint onto the tube and help fill in lumps and bumps created by the inner layers. Plus, it looks damn good!

Once it’s all dry, frames are buffed smooth manually…

…and mechanically. Then they’re ready for paint.

Well, almost. First, logos and/or graphics are masked, as are any metal dropouts when they’re used. Then it goes to the paint booth:

Paint is done by Shane Haverland, who comes from Serotta. He does some great custom paint, but also masks and paints the logos on all the frames. Nothing is done with decals. Examples:

Sometimes the work is very subtle, like their logo over their icon with a gloss clear coat.

Sometimes they get a little hit of color, which can be matched to components like the headset, bottom bracket, etc.

Sometimes they get a lot of color. Depending on clear coat or paint, the finish usually adds from 150g to more than 400g. Matt says raw Helios frames typically come in between 850g and 1000g depending on the size and build, before hardware and paint or coatings.

If you’re ordering a frameset, they’ll finish an ENVE cockpit to match the bike, whether that’s matte…

…or gloss. The seatpost in the foreground shows the sanded piece prior to getting clear coated.

Custom bikes are currently run through the entire process at once, molding the tubes to building the frame to curing, finishing and painting it all in one move. As they start to offer stock frames, they bulk build tube sets to create a more streamlined assembly process.

So, what does all this cost? Less than you might think, and actually pretty good compared to top-of-the-range stock offerings from the big boys. It’s $4,500 for a full custom Helios with frame, Cane Creek or Chris King headset and ENVE 2.0 fork, with a lead time of about 10 weeks.

Between 60-70% of their bikes these days are carbon. The rest are mostly…

STAINLESS STEEL & TITANIUM

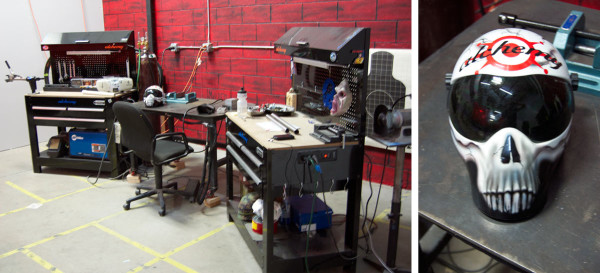

Jeff Wager is their welder. He worked for Serotta for 10 years, and with aerospace parts before that. He makes all of Alchemy’s metal frames.

This one’s KVA stainless steel frame and was headed for a Rapha Continental rider in Asia. We were on site long enough to watch it come together:

(a different, finished titanium frame on the right, awaiting paint)

This is as far as this one made it during our tour. But, this next one was already through polishing and showed another example of their painting talents:

Metal frames get etched logos, which also done in house in their own blaster.

All told, carbon included, they ship between eight and 20 frames per week.

NEW BIKES

While we were there, we got an up close look at the new Arion they introduced at NAHBS last year. Or, we got a look at one of the first prototypes.

The new Arion uses a flat trailing edge on the seat tube and seat post, the tubes are wider and the seatstay yoke is much, much thicker. Matt Maczuzak says his idea was to hide as much of the rear of the bike and rear wheel as possible, so the effective end of the air foil shape of the seat tube is behind the rear brake.

The downtube’s shape has been refined, too. It’s also wider, and the top edge is straight rather than convex like the original version. Matt says the entire thing proved faster in the wind tunnel, and bore the theory out that having a water bottle on the seat tube improves aerodynamics.

Chainstays are thicker to accommodate all the wider tubes by distributing the forces better. Up top, the seat stays have a bit thinner walls, which helps make the ride a bit more comfortable.

Not only is it now faster and stiffer, but also about 100g lighter. Matt says this frame is just under 1,100g, and it’s built for his racing weight of 220lbs. He says for a 185lb rider of similar height could end up with a frame another 100g lighter by removing material from the chainstays, downtube and other areas.

The entire project exemplifies why they’ve brought tube construction in house. While ENVE makes great carbon products, they don’t make complete bikes. Being able to build, ride and refine the tubes as a complete bike and test it all in the wind tunnel is helping them build some very unique, very beautiful bikes.

MORE PHOTOS

Huge thanks to Alchemy for showing us around!