It’s a fun idiom to say someone has reinvented the wheel. It’s even more fun when someone actually does, and that’s what friends Bobby Sweeting and Shawn Gravois, who both happen to be pro road cyclists and engineers, are looking to do.

“It’s been a year in the making, but it really started in college,” says Sweeting. “Both Shawn and I were racing professionally and would finish rides and have bearings failing, wheels flexing and just generally underwhelming experiences with the options available.”

It was December 6th, 2013, which happens to be Shawn’s birthday, and the two agreed that if they were ever going to make a go of it, that was the time.

“I pitched it to him as becoming a product manufacturing company, not a wheel company,” he said. “We didn’t want to come to market using just a bunch of open mold products with no real point of differentiation. So we took a hard look at what part we could design that would have the biggest impact, and have improvements or designs that we could patent.”

Their viewpoint was informed by more than just racing and an unrelated job in engineering – Sweeting was in rigid frame engineering at Cannondale, having designed the CAAD8, Trail SL and others, plus helping on the brakes for the Slice RS. And they had proximity to another cycling brand in Florida, where they went for winter training, that let them use machinery for prototyping. That shared equipment is what made it possible for them to get started on a shoestring budget while using advanced testing and research…

“The three main issues we’d continually run into as pro cyclists were: Durability (wheels falling out of true constantly and the frustration of hitting a pothole in a race and having to return to the team car to get a new wheel. It would ruin races), Lateral Flexibility (I’d stand up to sprint and have the tire hit the frame – not just the brake pads, but the frame!) and Bearing Wear (caused by imprecise tolerances that allow them to become slightly misaligned within the hub shell).”

The biggest question they had covered the basics of creating a better wheel: What is the best flange diameter, best flange spacing and best lacing pattern with regards to torque on the tire when sprinting and in corners? Shawn used Matlab to run an optimization problem that would relate the unknown hub geometry variables to lateral forces on the rim, an iterative process that would eventually yield optimal dimensions for the best possible wheel stiffness.

“Tom Frost, CEO of Datum, is big into cycling and was one of the first people we showed the design to,” said Sweeting. “This was February 2014 and we pitched him on investing and becoming a partner in the company, and when he said yes it allowed Shawn and I both to start doing this full time. We were prototyping at Sea Sucker in Florida, where our good friend Chuck let us use their machines, saving us a ton of money in the critical startup phase.”

THE DESIGN

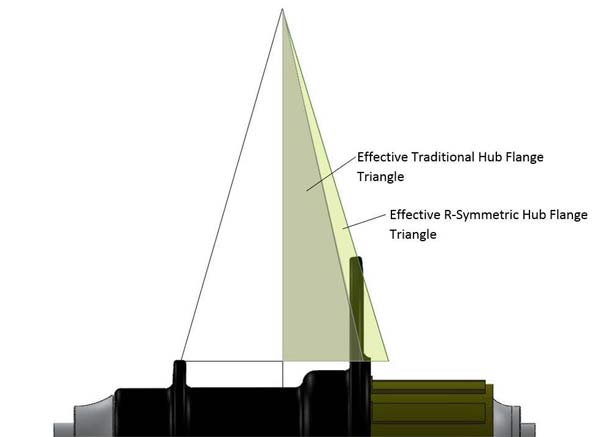

To create a stiffer wheel, all of their data said they needed to make the spoke base wider to increase triangulation, but how to do that within the confines of existing frame and drivetrain designs?

“Others moved flanges around, even moving the non-drive side flange inward to make the wheel tension more even,” said Sweeting. “It seems like so many companies are just guessing or just buying something off the shelf rather than really optimizing the hub design as part of a full wheel system.”

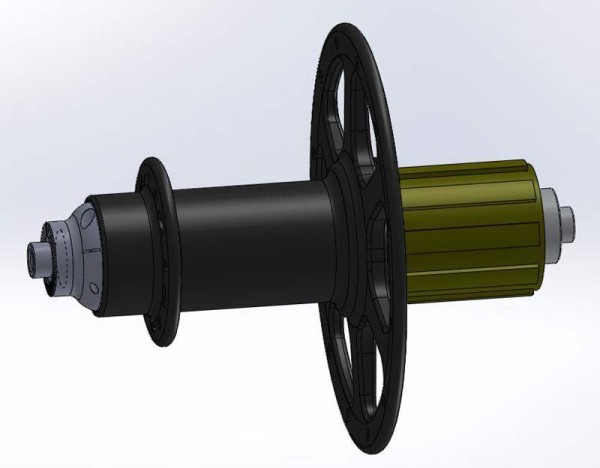

Their solution? Widening the base of the triangle by making a wildly oversized drive side flange.

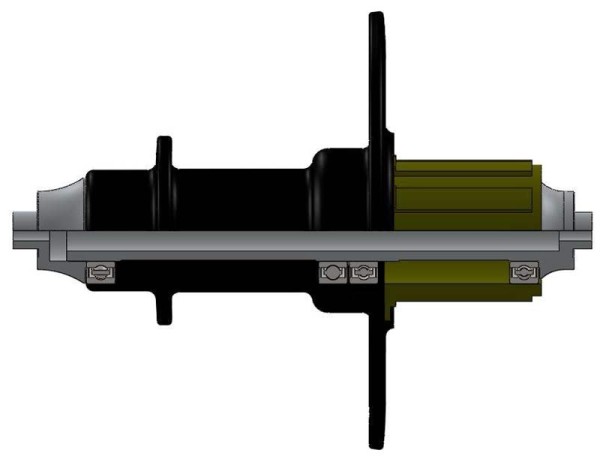

Flange width is 50.6, which they say is one of the widest in the industry. Amplifying that width is the oversized flange diameter, which is visually and functionally the most striking feature and effectively widens the triangle. The rear hub has a 109mm drive side flange diameter, spoke hole space diameter is 100mm. Non-drive flange is 38mm hole to hole (48.2 outside).

Tension is 120kgf on the drive side and 85kgf on the non-drive, where many wheels see about a 50% drop in spoke tension from drive to non-drive side. They could bring the non-drive flange in and even up the tension, but it would reduce the triangulation and make the wheel less laterally stiff. Getting the right balance between baseline width and spoke tension balance was the engineering problem they had to solve.

“Our R-Symmetric (stands for Right Symmetric) patent is really on the oversized drive side flange to optimize spoke tension on each side of the hub,” says Sweeting. “But there are so many other engineering decisions that make the hubs unique and better.”

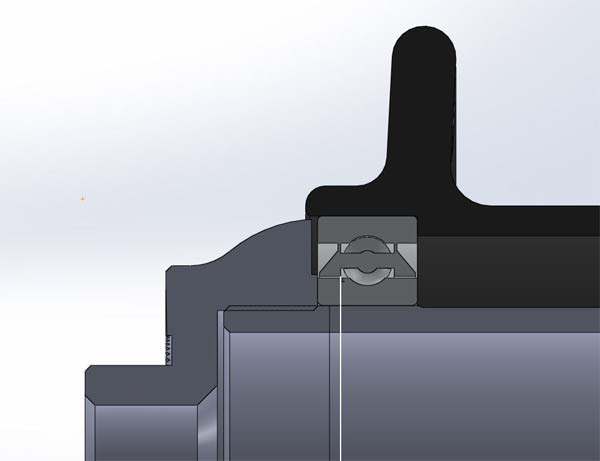

Things like machined labyrinth seals so you don’t need plastic bearing covers and ultra tight tolerances to keep everything aligned.

The hub shells are 6061, and the axles and endcaps are 7075. The way they come together serves to both protect the NSK non-contact bearings from the elements and prevent them from “leaning” under cornering pressure. The end caps thread onto the axle to let the user set the preload, then they’re locked into position with pinch bolts.

A labyrinth seal is created by having the shell overlap the endcaps by 0.5mm with just 0.15mm gap between the two. Sweeting says water would basically have to be coming at the end caps from a 90º sideways angle, which on a sideways rotating part is all but impossible.

“We spec really tight machining tolerances for the bearings, ensuring they’re firmly pressed in and held in alignment better,” Sweeting says. “It really came down to how the bearings are constrained, and our threaded axle endcaps come in and put the perfect amount of preload on the bearings to keep them in place without too much pressure to create drag but no looseness that could let them tilt.”

“This creates a stiffer, more balanced wheel and really increased the overall durability. We’ve taken them over some really rough, nasty roads and they’ve been flawless. And it doesn’t just help forward momentum, but because you’re not losing so much energy to lateral flex, they’re more energy efficient, translating all of your power into forward movement.”

The front wheel uses normally sized flanges, but keeps the axle-and-end cap system, overlapping design and labyrinth sealing design.

COMPLETE WHEELS

At launch, the hubs will mostly only be available on complete wheels, sold direct to consumer from their website and through shops. Standalone hubs will be available to select premium wheel builders that can build them up properly. All of their wheels are handbuilt to their specifications, using the right spokes, nipples, prep, lacing pattern and other considerations, which they say is critical to proper performance. And when they are built properly, Sweeting says you can completely loosen and remove one spoke and they’ll remain within a millimeter of perfectly true and strong enough to ride.

They’ll be laced to both carbon and alloy rims, both of which use existing rim designs, but the carbon models use a custom layup.

“We knew what we wanted for composites based on seeing the best practices used at (Cannondale),” says Sweeting, “but we had to find a manufacturing partner that could check all of the boxes we wanted, otherwise we were ready to open up our own tooling. Those requirements included building around an EPS foam core, allowing us complete control over the layup, a 25mm wide brake track that opens to 27.25mm wide section below it to create a toroidal aerodynamic shape.”

Alto Velo ended up at major Asian rim manufacturer that met those needs, which allowed them to save costs by using an existing mold while they specified the layup, which is what really dictates the ride quality. Sweeting said at some point they’ll likely open up their own tooling, but only to save on production costs and that it’ll keep the same exact shape.

The carbon rims will be offered in 40mm, 56mm and 86mm depths as both clinchers and tubulars. Claimed weights are (wheel / rim):

- 40mm carbon tubular: 1268g / 377g

- 40mm carbon clincher: 1471g / 478g

- 56mm carbon tubular: 1349g / 417g

- 56mm carbon clincher: 1566g / 526g

- 86mm carbon tubular: 1672g / 579g

- 86mm carbon clincher: 1875g / 680g

All wheels have a 20/24 spoke count with Sapim CX Ray. They’ll be laced radially on the drive side and 2-cross for the non-drive side. Retail will be $1,700 to $2,000 depending on model, with logo color options of green, grey, red, blue, yellow or orange.

For alloy rims, they’re using a 24mm wide (18mm internal) and 26mm deep rim that’s clincher and tubeless ready. It’s going to be around 1,402g and come in at $1,150.

Between the public launch and actually cranking up final production, samples have been sent to Germany to be run through the gauntlet of tests, all from the same facility that performs testing for Cannondale and Tour Magazine.

“Late last year we finished the near-final prototypes and took our first rides. Shawn rode them first and was blown away. I’ve never been one to notice minute changes and differences, but during our first ride, when we swapped bikes, my mind was blown, too. It was awesome.”

WHAT’S NEXT

They’re coming out with cyclocross and mountain bike specific wheels in 2015, which means that yes, they’re able to port this design to a disc brake hub. In fact, Sweeting says the models for those are done, they’re just launching the road wheels first.

They’ve also got eyes on cockpit parts, frames and more, all inside a five year plan.

“Just like ENVE started out with a focus on making bad ass rims, we’re starting with a focus on making bad ass hubs. But it’s still a system. This company is about engineering and innovation,” he said, “and wheels are just the start. We will be a product engineering company, not just a wheel brand.”

HOW TO GET THEM

The brand is launching on Kickstarter as this post goes live, check out the campaign here. It features some of their own internal deflection testing against well known wheels. The campaign has the usual schwag for smaller supporters, but it’ll also be your only chance to pick up a hubset on its own. Once the campaign ends, it’s complete wheels only. Hubs start at $500 for the pair, and complete wheels start with a $1,350 pledge.