Simple suspension isn’t limited to leaf spring forks, elastomer-equipped stems & double-decker flexing handlebars. Builders have been putting undamped suspension into bike frames for decades. More than meets the eye, we chatted with Moots about their iconic YBB design. And we found out that how their design deals with suspension damping takes a lot more factors into consideration.

How does undamped suspension work in a frame?

For the last couple of weeks we have been looking into what undamped suspension really is, plus why it makes sense in short travel forks and cockpit components, especially with growing gravel & adventure road disciplines that take on comparatively aggressive terrain. But undamped, or rather non-actively damped suspension isn’t limited to forks. We talked with Moots’ product development and production specialist Nate Bradley to get a look at the more complicated interactions that come into play in their YBB frame design.

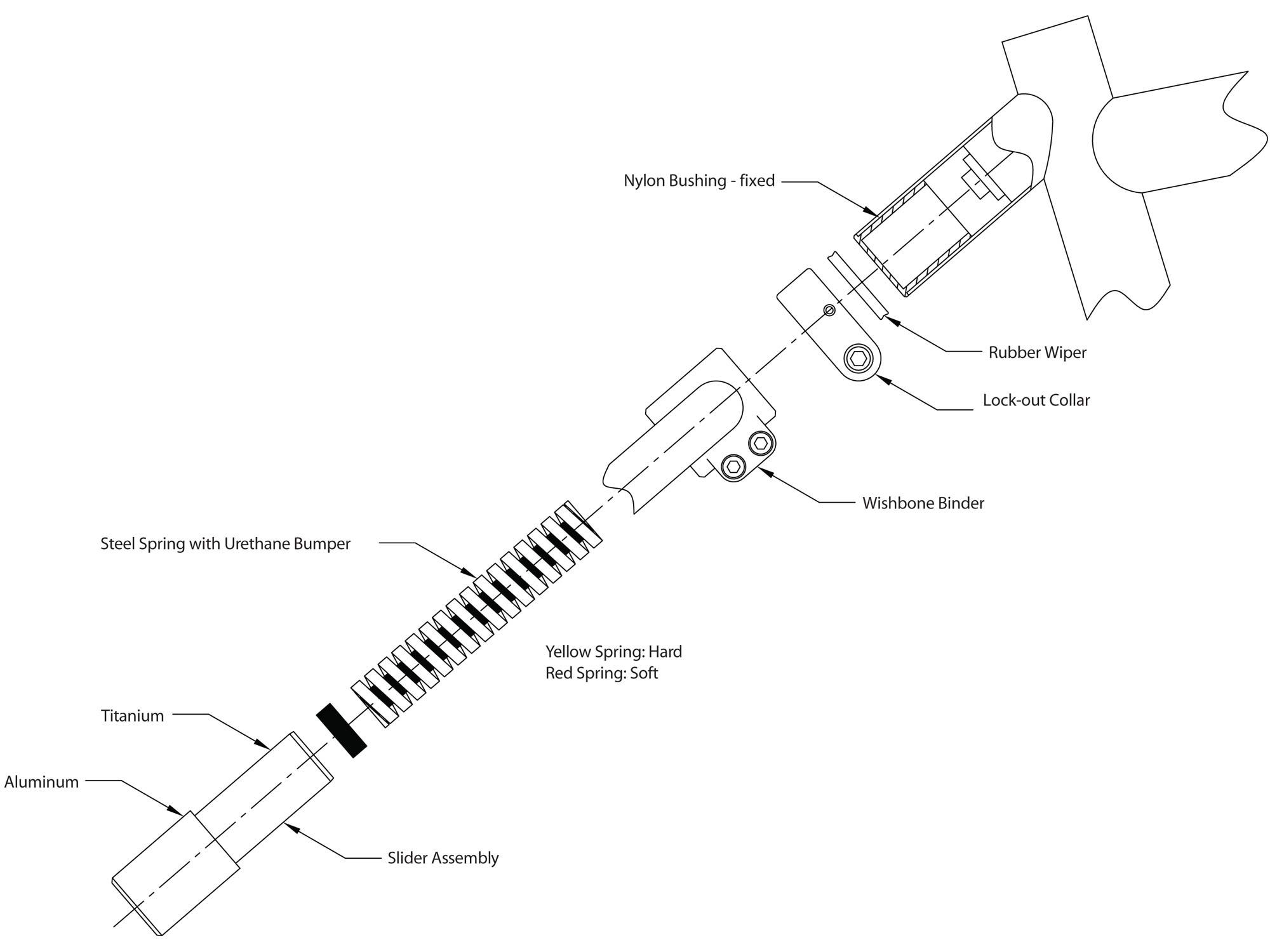

The same idea as in forks is here – controlling the energy of an impact that hits the wheel, before it gets to the rider. What’s unique in Moots’ YBB frame design is that even though we see a small slider with a concealed spring in the monostay just above the rear wheel, it is actually the frame itself – the titanium tubes of the chainstays from bottom bracket to rear axle – that act as the spring in the suspension. Just think if you took that YBB assembly in the monostay away, the frame wouldn’t fall apart, it would just become overly flexible since the chainstays’ spring is effectively undersized. (Take the leaf springs out of the Lauf on the other hand and there is nothing to support the fork to the front axle.)

That YBB assembly has a “coil die spring that controls compression and dictates rebound along with an elastomer that helps minimize the bounce of the coil spring.” Inside of the YBB wishbone at the top of the seatstays is a free floating (not fixed on either end) coil spring, which has the urethane elastomer fixed to each of its ends. Together, the coil-over-elastomer combo helps control the rate at which the chainstays flex. They are supplementary to the main springs, which are the titanium chainstays themselves.

The elastomer also prevents the coil spring from bouncing back too quickly. In the end, this allows Moots to engineer a fixed amount of rebound damping into the rear wheel suspension system, in a simple and lightweight way.

Does a passively damped frame only work for short travel?

As with undamped front suspension, the goal is the same in the frame – to distribute peak impacts over a longer period of time and allow the wheel to move up and down independent of the rider. “The goal is that the YBB takes the edge off the impact, separating the vibrations/impacts from the rider’s rear end and what the rear wheel faces along the trail.” The chainstays flex, the YBB compresses & rebounds, and the tire stays planted on the trail.

Moots acknowledges this solution reaches a limit pretty quickly. It’s easy for these types of designs and materials to get overwhelmed, at which point the YBB loses its simple comfort & compliance benefits. Nate says “the longer the travel gets, the more progressive the system would need to be to avoid unwanted bounce” or on the contrary they would have to build an “overly stiff and robust” frame to make it work.

Why not chose an actively damped design in the first place?

Moots has built YBB softail bikes since the late 1980s, and when they transitioned to titanium the material spring characteristics worked even better. Moots has also built a number of traditional pivoting & actively damped suspension frames over the years. But they stand by the YBB softail as a simple, serviceable solution that adds comfort without sacrificing much in terms of weight, pedaling efficiency, durability, or even aesthetics over a hardtail. A Moots YBB adds only a couple hundred grams over their comparable rigid hardtails, much less than a full suspension design. And while it does require some maintenance in the roughly bi-annual replacement of the titanium slider and its rubber seal, that is much less than suspension designs with hydraulic dampers, pivots & bushings. (And as you can see with this YBB and its neoprene boot to keep mud off the slider, if protected that service interval can be extended even further.)

And it doesn’t necessarily need to be limited just just to titanium (Moots themselves developed and built the YBB in steel first.) Plenty of other bikes incorporate flexing stays, like the old Castellano designed Fango in aluminum (that grew into a Ti Potts version more recently) and scores of modern bikes in carbon from the cobble-crushing Pinarello K8s to the XC & trail-riding Cannondale Scalpels that helped popularize carbon flex stays. In these shorter travel applications it seems like building the desired spring rate into the material of the chainstays is the only limiting factor.

How do you tune the passively damped suspension for each rider?

To design their passively damped suspension, Moots can size the chainstays to achieve the base spring rate they want – with six different spring rates generally available to start, and then varying tubing wall thickness to get the spring/flex they’re looking for. Then they can even preload the spring of the frame, so the YBB unit itself is effectively in its neutral state with the rider sitting on the bike.

Varying spring rates for the coil spring in the YBB allows Moots to control or damp the speed at which the suspension compresses. And lastly by choosing the urethane composition of the elastomer bumper Moots can determine how quickly the coil spring rebounds, kicking back through the chainstay spring.

Final thoughts on undamped travel in frame, fork & component design?

Nate tells us Moots isn’t “moving away from using undamped suspension in our frames anytime soon”. While you will find plenty of people “on both sides of the fence that like/dislike undamped suspension in forks and frames” there are certainly good arguments and applications for it. And those may even be expanding with the growth of gravel and adventure riding. While Nate has seen bars, stems, seatposts, wheels, grips, pedals & more try in some capacity to add simplified suspension “besides a frame, fork, and maybe a properly executed seatpost – a decent set of tires with the correct air pressure will have a greater effect for comfort for the rider than the marginal gains of other components.”

So that’s where we’ll leave it for undamped suspension design…for now. You aren’t likely to get a long travel downhill bike anytime soon that relies solely of flexing leaf springs in the fork or flexing chainstays in the frame. But if you are riding less technical terrain like cobbles, gravel and smooth-ish trails you may be able to find a simplified, undamped suspension setup that works for you where you won’t have to worry about maintaining hydraulic damping circuits.

The fun never ends. Stay tuned for a new post each week that explores one small suspension tech, tuning or product topic. Check out past posts here. Got a question you want answered? Email us. Want your brand or product featured? We can do that too.