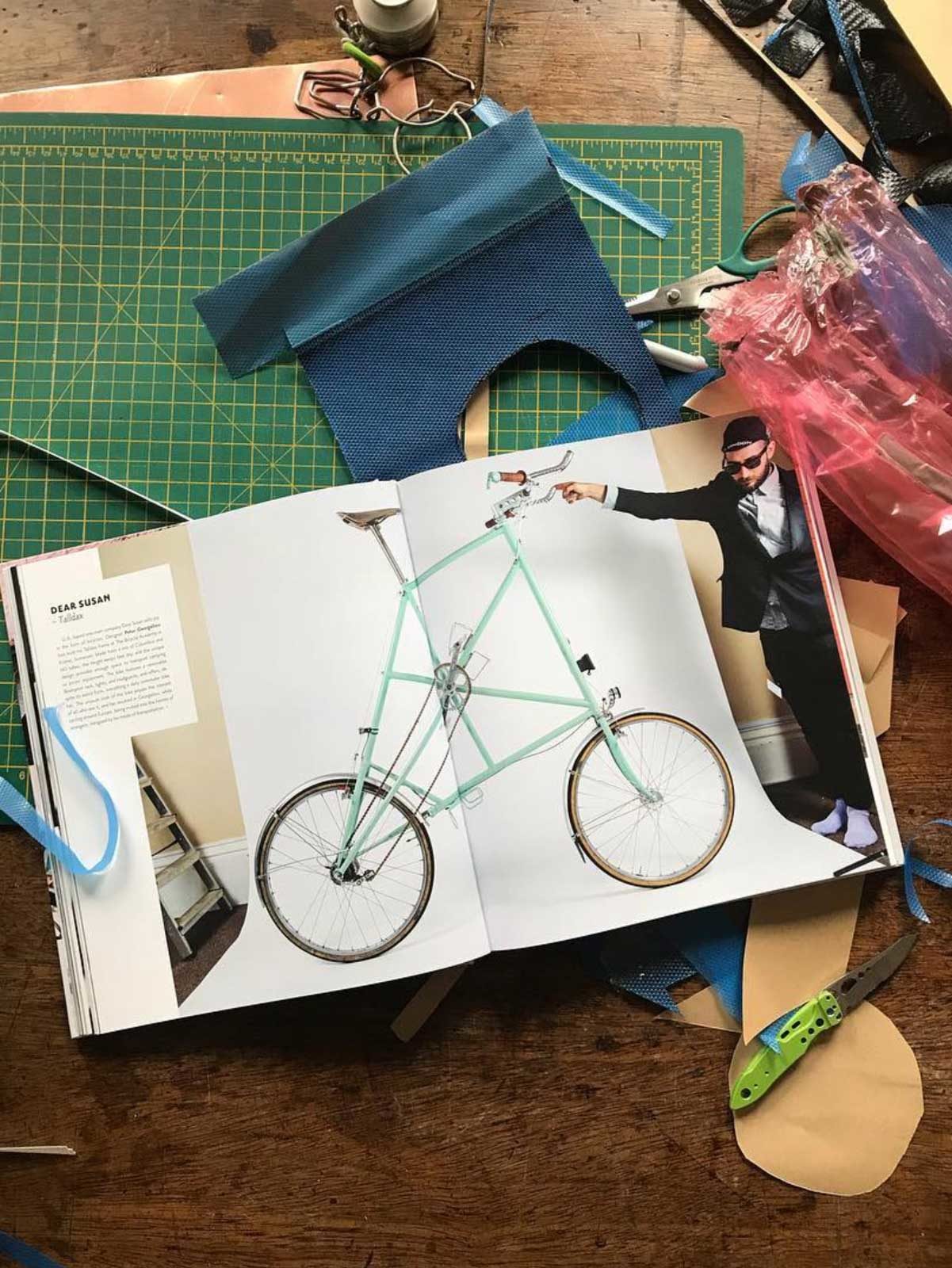

Brace yourself for Petor Georgallou!

The UK builder making his North American Handmade Bicycle Show debut this week is sure to be a breath of fresh air for even the most cynical and furrowed-browed cycling enthusiast. Petor comes at cycling from a place of fun, experimentation, and sometimes radical self-expression. But with his personal preference being for tall bikes, he’s had to work, through testing and expert advisement, to gain a deeper understanding “proper” bicycle handling, functionality, and geometry than frame builders who stay within a typical double diamond format. Meaning his bicycles aren’t just visually and functionally striking, but they are designed for a whole new world of riding experiences.

It’s all very exciting.

Petor is joining us in the U.S. due in large part to a collaboration with BicyclePubes, cycling industry critic and Instagram tycoon. In this, part one of our interview with Petor, we allow the builder to introduce himself and talk about how he came to be Dear Susan.

ANNA: How did you get into bikes?

PETOR: I was a really clever, really awkward kid. I didn’t really speak to anyone or have any friends. So bikes are a good solo activity.

ANNA: Ha! I think you said bluntly the same thing a lot of other people dance around.

PETOR: I got a scholarship to go to a really good school. I kinda wanted to go there really bad because it was in the woods and it had a pump track. But when you’re eleven, it’s like “Oh my god! This is the raddest thing I’ve seen in my life!”

Then I got into school, so my parents bought me a bike for getting in. It was my first okay bike. It was a Specialized Rockhopper

That was really fun for a year. And then some teacher had the pump track bulldozed, and that was kind of the end. I didn’t really cycle for the whole time I was at school. When I left school, it was like, what do you do in life now?

So I was like: I guess I’ll just go for a bike ride. And I did that all the time. I got into racing a little bit.

ANNA: What kind?

PETOR: Time trials.

ANNA: Really?!

PETOR: Yeah, I joined a road racing club. It was really cute! I really liked it. It was the best cycling club I can imagine. It was Twickenham. They meet in a church hall. You might have a cup of tea, go out for a ride, have another cup of tea and some cakes that the older people who run the club have made. Then you go to the pub and you have, like, one pint and you’re really drunk and you wobble home. It’s perfect. Really, really great.

I don’t know, it’s like everyone who races always breaks their collarbone. I really like my collarbone, so I mostly just did time trials. That way you die cycling into a tree or you don’t. And I probably won’t, so cool.

ANNA: Wow. I did not take you as a time-trialist.

PETOR: Time trialing is great because it is all you. You know? You’re not dependent on anyone else. There’s no tactics. Some people are like “you gotta think about your heart rate at this point” but for me, it was about going as fast as you can for a little bit, and then it’s the end.

ANNA: And then tea, cakes, and a beer.

PETOR: Yes. Perfect!

ANNA: How did you start building? How did that come about?

PETOR: I went to art school twice.

ANNA: Twice, not just once.

PETOR: Well, three times, pretty much.

ANNA: Why three times?

PETOR: I did an art foundation. Then I did a BA. Then I did an MA.

ANNA: Where did you go?

PETOR: The first two times were at Kingston, which was absolutely amazing. It’s on the Hogsmill [River], which is a tributary to the Thames. It’s where the painting of “Ophelia in the Rushes” was made. We were fucking about in the river and, you know, people would be tickling for eels, genuinely. That happened.

ANNA: “… tickling for eels?”

PETOR: You know, when you catch an eel with your hands?

ANNA: What does that entail?

PETOR: I didn’t do it. There was just a guy named Terrance who did it.

ANNA: You didn’t check that out?

PETOR: We did lots of fun things in the river. It’s really shallow and really, really clean, because it’s a really fast flowing river, which is why there are eels in it. But if it’s ever dry for a really long time, and then it rains really heavily, they empty all the sewage treatment water in there. It goes from this beautiful super clear nice stream – it just becomes this torrent of shit.

Anyway, I started building bikes at art school.

ANNA: For art school?

PETOR: Well, everything is for art school while you’re there.

I guess it never really occurred to me that people make bikes. I always made tall bikes and shit because it was fun.

ANNA: So your early bike experience was taking early bikes, cutting them apart, and experimenting with them…

PETOR: I remember racing a time trial and this guy – I remember him on rollers at the beginning, warming up. I was already like “pfft! Who is this prick on the rollers? Ride to the time trial to warm up!”

He was doing the best aero tuck I’ve ever seen. And he had these really mental handlebars. I was like “Wow, that is such a good idea! You can go so much faster with those crazy handlebars!”

“Where did you get those handlebars from?”

“I just made them.”

“What? Is that safe?”

“Is anything else safe?”

“What the hell is going on here?”

“I just glued them together out of some other handlebars.”

“You’re racing on something held together with glue?”

“Yeah! It’s awesome!”

I guess that was when I realized you could actually make a bike and do it well. “I guess I should try to make bikes well.”

I had been making tall bikes, bikes for carrying tesla coils. Stupid shit. We had a band and we didn’t know what to call our band. We were cycling in Spain and were like “We will see a sign and then we will know.” Basically after we said that we ran over a little metal sign that said “vado permanente.”

We were like, “This is it, that’s the name of our band.”

“But what does it mean?”

“I don’t know. Permanent Vagina.”

ANNA: You called your band “Permanent Vagina?”

PETOR: We called it “Vado Permanente” and when people asked us what it meant, we said “Permanent Vagina,” not knowing that it meant “No Parking Ever.” Some Spanish dude told us.

I made a bike for our band to do a gig on. We were all at Kingston, so we cycled up on this horrible three wheeled trailer where someone had to be on it steering, kind of cobbled together. It was me at the front with two other people pushing on a tandem. It was absolutely horrible. We came all the way to Hackney Wick to Kingston on this horrible thing, like a Halloween party, with all our instruments, battery amps, and synths, and drum kit – all dressed up in ridiculous Halloween outfits.

ANNA: For 30 miles!

PETOR: 30 miles, yeah. And then we got to the party and people would ask “What are you dressed up as?”

And we’d say, “Art school.”

ANNA: When did you decide to take it from a hobby to something more professional?

PETOR: I guess through all the bikes I made. They worked, but not properly.

It’s very frustrating having an idea and not be able to realize it, just through lack of technical knowledge. I would always try to do a thing… a lot of times it would work out but sometimes it wouldn’t. I’d do something and I’d change it a bit and I’d change it a bit and I’d change it a bit… until it did work, at which point it was so chopped up and messed around with that it wasn’t as good as it could be if I had just done it right to begin with.

I just got tired of the process of learning being so slow and so expensive. It was that and finding out what The Bicycle Academy was, that there was someone teaching this.

ANNA: What is The Bicycle Academy, for those who don’t know?

PETOR: The Bicycle Academy is really nice. It’s a frame building course where you go and build a bicycle frame. I think because I did my course very early on before anything was really settled, when The Bicycle Academy was new, I think their lack of experience meant that they were so much more generous with their time than they should have been, really.

I looked at the courses they did, but nothing was quite what I wanted. I ended up doing a custom course designed around me for what I wanted to do.

ANNA: Why? Was it so custom it required its own course?

PETOR: It was complicated because the course is not set up for building tall bikes.

There haven’t been enough people building tall bikes with actual, serious intention for there to be any rules or knowledge or understanding about handling and geometry and how they really work. I actually did a lot of research, but I didn’t know what I was doing. My research combined with The Bicycle Academy, which is a pretty broad spectrum of people.

ANNA: The obvious interview questions: what are the unique challenges of designing and building a tall bike? How did you solve those unique challenges?

PETOR: I took all the mistakes from previous tall bikes and tried to rectify them all in one bike. Tall bikes wheelie because the back end is too short. So I made it longer. Tall bikes are quite twitchy as well, so I sorted that out and had a bit more trail.

I tweaked the geometry from what I learned from my previous builds, but I had a lot of help from Tony Corke, who is Torke Cycling, who does bike fit. For me, I’ve done a couple bike fits – he’s done the best bike fit I’ve ever had. He’s got a good approach to it. He helped me a lot with the design. I wanted to design it around super long distance riding because you’re not going to win any races on a tall bike. So what’s the next most ridiculous thing you can do?

I used it as a touring bike –

ANNA: You used this as a touring bike?!

PETOR: Oh god yeah. Yeah yeah yeah, loads! That’s what bikes are for!

ANNA: Well, all your bikes are rideable bikes.

PETOR: There’s no point otherwise.

ANNA: You build a lot of tall bikes – but the thing that makes me interested in what you do is that you have this highly technical and experimental repertoire.

Bespoked 2016, where I met you, you had a modular triple that could become a tandem. You had the righty Pinion carbon mountain bike. You had the real tree mountain bike. You had a reverse brake polo bike, and a compact. All in one booth.

I walked up and I thought it was a collection of several builders at first. Then I wondered if it was a prank… because in the middle of Bespoked, in the middle of a sea of perfect, polished, road and randonneur bikes.

Functionally. Thematically. Visually. It is an overwhelming portfolio, but it’s a space you’ve really owned.

Did you go into it deliberately to be a wide ranging builder? What motivates you to be so broad?

PETOR: Some people are clever and can just dial down exactly what they want to do and do it, but how can you just do A thing? Imagine building all those bikes you saw there in two or three months and –

ANNA: I saw, and I can’t imagine!

PETOR: – and then thinking “I’ve got to pick one of those bikes and that will represent what I do.” How do you pick?

ANNA: Well you didn’t.

PETOR: Yeah, exactly. A sensible person would have chosen one or two and then had a small booth. But I was like, “I can’t choose! So instead, find a way to pay for a bigger booth.”

ANNA: The following year, you brought this Cleland-themed bike. We should talk about that.

PETOR: Oh god, I love that bike so much. It’s broken. I’m happy it’s broken! It’s good. It should be break. I rode it in the sea!

ANNA: For our viewers, please explain what a Cleland is.

PETOR: Cleland makes a bike designed by Geoff Apps, who was a motorbike trials rider. This was in the 60’s. Mountain bikes didn’t exist in the UK at the time. Not even clunkers. You had racing bikes or a roadster or a touring bike, or a Moulton, but it would have been an F-Frame Moulton. That’s all you had in the country. You didn’t have BMX. Specialist touring parts had only just started popping up.

Geoff wanted something that was really stable and solid but that shared a similar geometry with a 50’s trials motorbike. Super stable where you can ride over anything without getting stuck – just in silence. Imaging going through some really beautiful woods – woods in England are really muddy and boggy. In the UK, it’s all bogs.

ANNA: Just one big bog.

PETOR: Pretty much. The difference between a Cleland and a mountain bike, which kind of came to pass at similar sort of times. Geoff Apps has loads of really good letters between him and Gary Fisher about, like, tires.

He took the geometry of the trials motorbike and used what touring bike parts existed and made a few of his own things, like drum brakes. He wanted to make something that was as sealed as possible from the elements, that protected the chain from the inside so that mud from the rear tire doesn’t go on the chain rather than stop chain grease from getting on your leg… because that doesn’t matter.

That’s the best bit of the bike. That and this very British way of looking at design, like “if rubber bands will work, use rubber bands!” It almost fetishes how little you can get away with rather than make something last. I don’t need the best bearing ever, I need a bearing that will keep the mud out and, when mud does get in, I can service. I don’t need the best chain, I just need mud to not get onto it so it will stay clean and will continue to work.

Whereas mountain biking took a very different approach, like “I can make it better by making it lighter/stiffer/stronger/better/mad,” there was none of that with the Cleland. There was just “this is better because it does the thing, and nothing else does the thing.” He couldn’t even get tires for those things. The Cleland I have is 650b when nothing was 650b, because the only tires he could get were ice tires from Sweden. They were knobbly tires with spikes on them that would go on Swedish town bikes on the winter when everything froze over.

ANNA: You had this actual Cleland bike on loan from a shop. Why did you want to build your own riff on it?

PETOR: Because it’s amazing for all those reasons, but it is absolutely terrible for a lot of other reasons. It’s much too flimsy. They used [Reynolds] 531 tubes but really small diameter 531 tubes – which kinds of makes it amazing because the whole thing noodles around. You hit a rock and the whole thing noodles around it. Actually, that’s something the bike I built didn’t have – I did build it to be noodly, but it wasn’t as noodly as the Cleland and there was something lost in that.

ANNA: It’s stiffer and a little more robust. It has a Pinion drivetrain, and a matching special PAUL Components kit. The bike has a swampy theme to it with curvy tubes and patinated copper like it just crawled out of the sea. Can you talk about how you developed this theme?

PETOR: The curves were referencing James Black Sheep, Moonmen, and Oddity, who are all American builders I’m just super fascinated with because they build awesome bikes… that seem to be better than anything else in my opinion. But, you know, what do I know? Not a lot.

ANNA: They are pretty fabulous. You’ve met James Bleakley.

PETOR: He’s a legend. He shows up to an English bike show, no one knows who he was. I’m like “OH MY GOD YOU ARE SO AMAZING.” He wasn’t a massive dick about it. He’s just a nerdy dude that builds awesome bikes. I guess that’s all you really want from a person.

And PAUL stuff – I really love PAUL stuff. It’s just simple enough for my brain to understand it. I feel like modern bicycle parts are standards for standards’ sake. Sure, hydraulic brakes feel better, but if you break a seal on a Hope brake, you’re fucked. Especially if you’re me! I don’t think I’ve ever successfully bled a non-Shimano brake.

With a cable disc brake, you know where you’re at. It does what it needs to do and nothing more. And they are simple enough to completely disassemble them and anodize them how I like. You can just look at it and see how it goes together and in my head, that’s very good design.

Aside from that, those very expensive components, which are a lot more expensive here than they are in America, but everything is expensive here because our economy is shit, are the cheapest parts I’ve ever bought in that they look really really fancy and they are really really fancy – they were the same parts I used the year before on a different bike.

My bikes – I basically ride until they break. And then I make a new one. And that’s kind of the same with components. I just run them until they are completely dysfunctional.

ANNA: What was the response to your Cleland-themed bike? Was there any kind of pride around it being this English mountain bike?

PETOR: The response was amazing. I was actually really surprised by the response to the cultural reference I was bringing to the show. That was really rewarding. The other thing is that this isn’t a mountain bike, and that’s what it was about for me. It’s a completely different evolutionary path of off-road bicycle riding. It’s like a bicycle for dog-walkers, like, “I’m going to go hang out in the woods. I’m going to go for a gentle potter!” or, “I’m going to go walk my dog except I’m going to ride my bike.”

Mountain bikes I feel are so much more performance-based. There isn’t Cleland racing – you wouldn’t win anything on a Cleland. Mountain bikes are designed for going up and down mountains and racing across country, whereas Clelands are for going to visit your granny for a cup of tea.

ANNA: The next bike I think of with you is the “Princess Freedom” bicycle you did with Grayson Perry. How did that come about?

PETOR: Grayson Perry is to BBC in terms of fine art what David Attenborough is to the BBC in terms of wildlife. He’s kind of an institution.

ANNA: Grayson Perry finds you to build this bike.

PETOR: He’s a mountain bike racer. He races them very seriously. He’s a lot faster than I am. He’s a speedy, gnarly dude.

When he was starting out, he was part of a really punk scene. He doesn’t often commission other artists to make his work – working with him was amazing and terrifying.

ANNA: What was the ask exactly? Because the bike is bananas.

PETOR: It was to design and build a big little girls bike that he could ride around town. He wanted it to handle like a bike but be as big a possible, so he would be the scale of a little girl riding a bigger bike. A big part of the brief was making it as physically large as possible while still being normal while you’re riding it.

ANNA: Is that something he’s riding?

PETOR: I know that when I first dropped it off, he was riding it from his studio to the gallery for the first showing of it, which for me is just so cool. I thought, “I’m such a cool dude, I’m just riding this bike from my studio to his studio, look how cool I am.”

And then he was like, “Yeah, that’s just how you get bikes around. You ride them.”

ANNA: In addition to this Grayson bike, you’ve done some really cool adaptive technology projects.

PETOR: That’s my favorite thing. That’s what it was all meant to be about to start with. Then, I could make sculptures – I did a sculpture MA and I was making films and sculptures. “I can trick people into buying an artwork by thinking its a bicycle, because why would anyone buy an art when they could build a bicycle?“

That was the plan but that was absolute lunacy. I thought quite seriously about why people even need a custom bicycle and adaptive technology is basically the only reason. For mobility bikes, there is quite a lot of funding out there for people to have them made, and they work best on a one-to-one scale of the person who needs the technology working with the builder.

If they can get funding to do it, it is completely different than someone saving up money and paying you for something, because they want something that’s going to work and change their lives in terms of functionality. That’s much more interesting to me – it’s a much more exciting way to work because you’re solving a problem and there’s a clear right and wrong in terms of design. It does the thing it’s meant to do or it doesn’t do the thing it’s meant to do.

There’s definitely bikes, especially like something like Grayson’s, where I was given creative freedom. The bike I’m building at the moment does have a lot of creative freedom. There’s a huge amount – 80% of the work I do I don’t show because it’s just, what is there to show? It’s frame repairs and normal bikes for normal people.

I have nightmare projects all the time. The Grayson thing was a nightmare project but it was incredibly valuable and gratifying. That three person tandem that broke apart and became a two person tandem when the kid outgrew riding with his parents – that was a nightmare project but the guy was really nice about it, and we worked together on a project. It came together and he liked it. It did what it was meant to do.

That’s why I really love doing adaptive technology projects because the customers are appreciative that I’ve made something happen to them that wasn’t going to happen otherwise. That’s what custom, at the core of it, is really for. Art bikes fit into that category also because in a sense they are subversive. It’s like going to an art show dressed up as a clown because it all really is a big circus.

ANNA: That seems like a good segue to NAHBS. Have you been to The States before?

PETOR: I’ve been two times. I went to Disney World with my parents when I was five. The only thing I cared about doing was going on a hovercraft into a swamp to see alligators. The day came for going into the hovercraft into the swamp, and there was a massive lightning storm. We couldn’t go in the swamp. We sat on a bus and watched Sister Act.

ANNA: What?! That’s the opposite of alligators!

PETOR: That *IS the opposite of alligators! I love Whoopi Goldberg as much as the next person, but not as much as alligators.

The other time was when I was 21 and my sister was 18. It was my parents wedding anniversary. We went to Las Vegas and Hawaii.

ANNA: As you are right now, what is your perception of NAHBs or of the U.S. independent builder community? What makes a U.S. builder a U.S. builder?

PETOR: My perception of American builders is – if I were an American builder, instead of having a four meter by six meter room with no light or no ceiling or no heating and only one working plug circuit, I’d have space five times that size. I’d have a milling machine set up for mitering front triangles. Another milling machine set up for mitering chainstays. And another milling machine set up for mitering seat stays.

[As Petor speaks, loud quacking begins in the background.]

Hold on, I have to deal with a duck.

[There is scuffing and more quacking. Then, quiet quacking in the distance. A pause.]

Okay. Continue.

ANNA: How many milling machines do you have?

PETOR: Hold on, let me count… hmm… None.

ANNA: You have some electricity… it’s just not extensive. In your neck of the world, space is expensive, machines are expensive and they take up space so they are doubly expensive. Also, builders in that part of the world learn how to build with a file and a hand saw – that’s what The Bicycle Academy is big on.

PETOR: That is correct. I think that’s a really good way to learn, the first few frames you build, because it forces you to work slowly. That’s a good thing. It means you don’t wind up wasting loads of material, you understand what you’re doing better. In terms of running a course, it’s nice because the workshop is quiet and you talk about stuff. There is so much learning to be done through talking about stuff outside of the physical making, which you just wouldn’t get in a machine-based course.

Also, for a course to be machine based – it would have to be months or something. There is so much more to learn.

I guess my perception of American builders is that they have more machines and come from more of a precision machining background, and more geared up for manufacture than builders in the UK.

ANNA: What about NAHBS in particular? Bespoked, for context, is quite a bit smaller, in a smaller venue with all this natural light. Builders are from all over the world – far more international than NAHBS. What are you expecting from NAHBS?

PETOR: I feel like you’ve shattered a lot of my expectations already. For one thing… is there not going to be any natural light in there?

ANNA: Oh, oh no.

PETOR: You’re fucking kidding me! It’s in California!

In my head, Bespoked is like when you have a, I don’t know if this exists in American, but a village fete.

ANNA: What is a “village fete?” It sounds precious. I’ve been watching a lot of the Great British Baking Show lately.

PETOR: That’s the vibe! A village fete is when everyone in a small town or village gets together and has a fun day of celebration. They have egg and spoon races or three leg race or a bake off.

ANNA: I feel like I’ve seen this on Jeeves and Wooster.

PETOR: Yes! They do exist! And the vicar is there just, I don’t know, doing something vicarish and there’s some stupid game that doesn’t have any outcome but is somehow competitive like, I don’t know, throwing a sponge at a duck. I don’t know. “Of course! It’s the annual throw the sponge at the duck competition!”

In Molesey where I grew up, we have the Molesey Carnival. A bunch of local businesses each make a float, which is themed, and then there is a guy dressed up as a mole playing a big drum and he just marches through the town with the floats. At the end, you’ll meet on the village green and you have to judge the floats. Someone wins “best float” and someone wins “best costume” but there will also be “who can hit this thing with the hammer the hardest?” or “who is the best at throwing a pie into a bush?” How do you get good at it?! You’re literally running on your natural talent of how well you throw a pie into a bush! You don’t practice throwing pies into bushes!

ANNA: Is that what you’re so upset about? That there isn’t a way to train for it in the off season?

PETOR: My frustration is that people are competing about throwing pies into bushes or sponges at ducks. They are such arbitrary yardsticks of a person’s worth.

And that’s Bespoked.

And then the vicar’s going around telling you off like a naughty school child for spray painting a SILCA frame pump in the car park. Then the fucking school bully comes along who is some other frame builder who I don’t even know his name is like “Why aren’t you listening to what the vicar is telling you?” and you’re like, “Who the fuck are you and what difference does that make in your life?!”

That’s Bespoked.

For me, at NAHBS, I will be the kid that’s used to going to that weird village fete every year from conception then going to a house party full of teenagers, but then expecting there to be a duck sponge contest.

People are just like, “No, it’s not about the duck sponge. It’s about how many weird red cups of low quality ale you can consume in a minute.”

And you’re like, “No! I’m not set-up for this!”

It’ll be like village fete to frat party. That’s how I see this going. I will do what I do in a frat party situation… which is probably to pace up and down chanting my mantra:

“I’m Louis Theroux.”

Tune in tomorrow for the thrilling second half of this interview wherein Petor talks about his collaboration with Bicycle Tiberius Pubes, world famous cycling culture critic and social media darling, The PUBESMOBILE.