Over the 21 stages of the Tour de France, riders of the Pro Peloton may ride a number of different models from their frame sponsor. They will switch between the brand’s dedicated aero road bike, time-trial bike, and lightweight climbing bike, making a decision based on what that stage will bring on the day; elevation profile, wind conditions, mileage, terrain, etc., all need to be carefully considered to ensure the rider is optimally equipped. The team looks to control any factor that is controllable.

We recently received a thought-provoking question from a reader on this very topic, a question that was the inspiration for this feature. Not being aerodynamics specialists or engineers ourselves, we have recruited expertise from some of the top road frame manufacturers whose bikes can be seen throughout any Pro Peloton. Specialized, Trek, Cervélo, and Cannondale all bring some interesting and insightful discussion on the topic, ranging from the succinct and easily digestible to the results of some rather revealing virtual simulations.

The Reader’s Question

“The gradient at which it is said that weight begins to trump aero is typically around 8% for pro riders. Obviously, the slower one can ride and climb must affect this transition point in gradient. How does this gradient transition reduce as the available power output reduces for those of us who are not pros?”

The answer to that question is, it depends, as we will soon find out from our team of experts. The discussions offer some insight into bike choice in the Pro Peloton but also deliver some golden nuggets of advice as to what kind of bike we amateur cyclists would go best on.

Our contributors are:

- Marcel Keyser, an engineer with the Specialized Human Performance Team

- The Cervélo Engineering Department

- Trek Senior Aerodynamicist, John Davis

- Dr. Nathan Barry, Cannondale engineer and aerodynamicist

Dr. Nathan Barry, Cannondale Engineer, and Aerodynamicist

The simple answer is that the less power to weight a rider has, the slower they climb, and the lower the gradient of the tipping point between aerodynamic and weight savings. But that only scratches the surface of this phenomenon. To fully address this question, it’s important to go back to the fundamental science that underpins this concept to make sure there are no misconceptions. The statement of one specific gradient where weight trumps aerodynamics is an oversimplification from some arbitrary specific set of parameters.

The underlying mechanics of cycling, described by the cycling power equation, show that aerodynamics is a function of velocity, with no dependence on gradient or mass. Conversely, climbing power is a strong function of mass, gradient, and velocity. Taking the extreme edge cases; on a flat road (0% gradient) a rider expends 0 W of climbing power. At a constant speed, mass has a minimal impact on the power required, thus most of a rider’s power is spent overcoming aerodynamic drag. As the road gets steeper, the rider must expend climbing power, leaving less power to overcome drag, therefore their speed drops. So at some very steep gradients, a rider will have very low velocity such that aerodynamic resistance becomes minimal and the majority of the rider’s power is spent overcoming the gradient.

It stands to reason then, there will be some cross-over point along this gradient spectrum at which the rider expends an equal amount of power overcoming both drag and climbing power. However, this still isn’t the full picture. The question of interest isn’t about the magnitude of power, but rather differences in performance. What we are really interested in is how changes in drag or mass affect performance. A simple example might be a choice of wheels. A shallow wheelset might be lighter but sacrifices aerodynamic efficiency compared to a well-engineered deeper rim. Clearly, on a flat road the deeper, low-drag wheelset is preferable. The question becomes, how steep does the road need to be before the lightweight wheels are faster than the heavier but lower-drag wheels? Often this is referred to as the tipping point.

What becomes clear from this example is that the gradient at which the tipping point occurs will depend on the relative difference in drag and mass. A big drag savings with a small weight penalty will have a much higher tipping point than a change that has a small drag savings but large weight savings. The tipping point is also a function of velocity. Even when climbing, a rider is pushing through the air so there is always a component of aerodynamic drag. While it is reduced at lower speeds while climbing, it never drops to zero, so long as you are moving. As noted in the question statement, this is the reason why the tipping point is higher for professionals. Due to their higher power (and power to weight), they climb faster, and at a given gradient, they are traveling faster than an amateur and so have higher aerodynamic resistance to overcome. Aerodynamic savings have a larger influence on performance.

A second concept to layer on top of this is that these differences in rider performance are related to the system as a whole, not just the component, or the bike. Consider a wheelset upgrade that saves 100 g of weight — ignoring any aerodynamic differences for now. For a high-performance wheelset in the range of 1,600 g, a 100g reduction is a big saving (6.3%). For a complete bike of ~7.5 kg that would be a 1.3% weight reduction. However, cycling performance is determined by the total system mass — including the rider.

Typically, the bike is only about 10% of the total system weight. For a 75kg rider on this bike, the 100g weight savings is only a 0.1% reduction in system mass. As such, the climbing performance improvement from such a change will be proportionally small. The same is true of differences in aerodynamic drag. Changes in drag need to be considered as a function of the whole system. However, a 10% reduction in system mass is impossible when considering only the bike, this is not out of the realm of possibility when you consider a bike with no aerodynamic optimisation versus one dedicated to lowering drag.

How does rider power affect the gradient transition? There is no one answer to this; it comes down to those three key variables: change in drag, change in mass, and rider power to weight. For a given configuration (a given difference in drag and mass) you can model a curve for tipping point versus rider power to weight. This will show how your performance with a given setup compares to that of a pro who might have significantly higher power to weight. But that will only apply to that specific equipment configuration. As soon as you change the relative differences in drag and mass, the model will no longer be relevant. It is hard to simplify this since differences can vary widely. Between wheelsets, frames, cockpits, helmets, and clothing, there can be big differences in both drag and mass.

To try and provide some insight to those who don’t want to build all this into a spreadsheet, we can frame some of these principles in a less complex way using a very simple case study. Consider what happens when you add 1 kg of dead mass to your bike, i.e. with no benefit from reduced drag. In the context of high-performance road bikes, this is a big change in bike weight. Certainly, something that a rider will feel when they hold or pick up the bike. Most road riders would consider this to have a dramatic impact on performance. If we take a case study for an amateur rider: a 75kg rider, 7.5kg bike, 7% gradient climb, 15km/h road speed. Climbing at this speed and slope would require ~275 W. An amount sustainable for a fit amateur rider of this size (3.7 W/kg). The addition of the 1kg dead weight would add only 3W resistance under these conditions. This is not nothing, but it is just a little over a 1% increase in resistance. For a rider who isn’t competing at a high level, this difference is not going to make or break their ride. In fact, this equates to less than 0.5-second time loss over a 5km climb. If we reduce that performance to 2.5 W/kg the power difference is 2 W and the time difference is 0.5 seconds to the same significant figures. Basically, less power available reduces road speeds, which reduces the magnitude of power differential but increases the time saved — since the rider’s total time over the segment is proportionally longer.

Weight is not as significant as most riders probably believe. Even with no aerodynamic improvement, a 1 kg difference has a relatively small impact on road speed. Conversely, if you start with a setup that has relatively high drag, a 1kg mass difference could be spent on a huge amount of aerodynamic optimisation. For the same rider and power output you could see at least 20W power savings on a flat road when comparing a classic round tube frame with low-profile wheels to a modern race bike. So perhaps a simpler question to address this phenomenon is how much should a rider care about weight or aerodynamics? While it is much easier to feel and measure the weight of a bike, for almost all riders and scenarios, aerodynamic optimisation will have a much greater impact on your on-road speed than reducing the weight of the bike.

If we revisit the wheel comparison from earlier, we can consider one specific equipment choice and examine the calculation of the tipping point for our 75kg rider at 275 W. Take two wheelsets: the first is lightweight at 1,300 g but has a shallow rim and high drag. The second uses a deep aerodynamic rim with a weight of 1,500 g and a drag reduction of 0.010 m2. This represents a realistic figure based on wind tunnel test results for a pair of wheels on a complete bike.

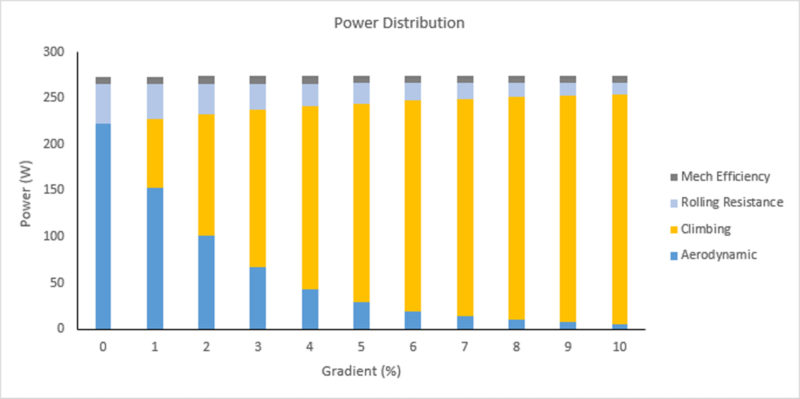

The power distribution as a function of gradient for this rider is plotted below. This model effectively has the rider maintaining a constant power output and redistributes that power based on the requirements at each gradient. From experience, we know that the increase in gradient is coupled with a decrease in speed. At 0% the rider is moving very quickly (~38 km/h), compared to very slowly (~11 km/h) at 10%. This plot highlights how the rider’s power distribution changes as the road becomes steeper. With increasing gradient, there is more power required to overcome the elevation gain, leaving less power available to maintain the speed seen on the flat. As speed drops, so does the aerodynamic power requirement.

For the two wheels, we can calculate these power distributions for each configuration. Comparing the two sets we can derive the tipping point to occur at a gradient of 6%. Remember that this is the inflection point. At any gradient up to 6%, the heavier, lower-drag wheelset is faster. Only once the gradient exceeds 6% is there any advantage for the lighter wheelset. Note, in the above graph, that at a gradient of 6% significantly more of the rider’s power is distributed to climbing compared to air resistance, and yet the performance of the two configurations is equal at this gradient. This comes down to the relative impact of those differences on the performance balance. As described earlier, changing rider power, drag savings, or weight savings will change the value of the tipping point.

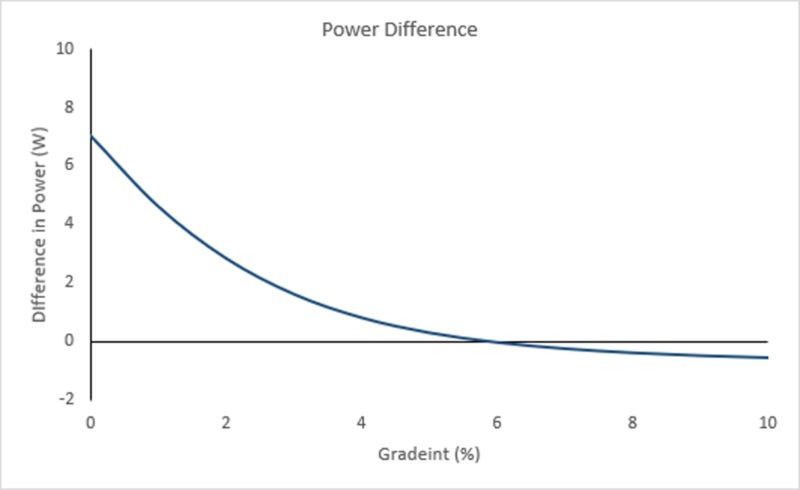

The figure above shows the power difference based on a fixed velocity (as calculated for the first configuration with the heavier, lower drag setup). In this case, positive values indicate the additional power required by the lighter wheelset, negative values indicate where the lighter wheelset is saving power over the heavier wheelset. The horizontal intercept at 6% indicates the tipping point. Note that the magnitude of power difference between the two configurations is not equivalent. Whilst the lighter wheelset is faster above 6% the power saved is an order of magnitude smaller than the savings seen with the low drag wheelset on low gradients.

Cervélo Engineering Department

Aerodynamic impact grows non-linearly as speed increases. Pro riders produce more watts and weigh less, which results in a faster average speed — which also means the absolute aerodynamic impact is greater.

Relatively speaking, on flat ground, an amateur rider will benefit more from an aerodynamic frame than the pro rider because they produce less power and typically weigh more, and the aerodynamic reduction in drag is a greater percentage of their total power output.

Once the road goes uphill, though, weight becomes the determining factor, and speeds drop. A pro rider will still produce more power and weigh less than an amateur rider, so they will maintain a higher speed, which maintains aerodynamic performance. An amateur rider will weigh more and produce less power, so their speed will drop more quickly than a pro, also reducing the aerodynamic impact of the bike.

Assuming bike weights are the same, along with the assumptions stated above regarding power output and rider weight, the weight versus aero tipping point for the average rider is likely around a 4-5% gradient versus approximately 8% for the pro rider.

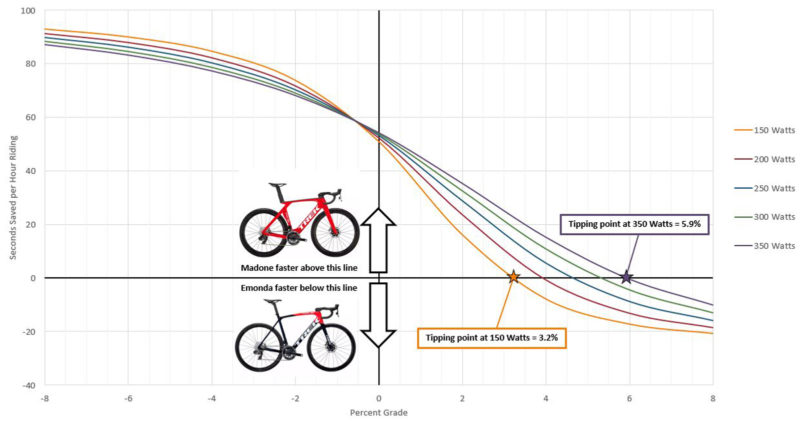

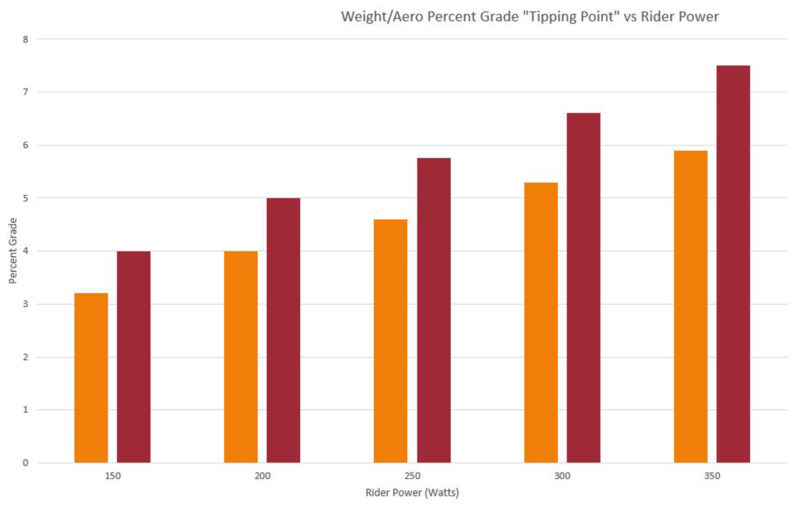

John Davis, Trek Senior Aerodynamicist

The reader’s 8% tipping point was accurate several years ago for the trade-off between typical aero and lightweight bikes at pro speeds. However, with most race bikes receiving aero treatment nowadays, that tipping point has been reduced.

(Assumptions: no wind, 73kg rider, equal rolling resistance for both bikes, baseline CdA of 0.3, hands at same hood width for both bikes.)

Keep in mind that on a loop course, you must descend what you climb. Factoring in descending, the Emonda versus Madone tipping point for an out-and-back climb and descent changes from ~3% to ~6% for the 150W rider (this simplistic calculation neglects braking losses).

Now, almost all race bikes receive some aerodynamic treatment, which has reduced the tipping point from the ~8% level the reader asked about. This example compares our 2018 Emonda versus our 2021 Emonda, but the same trend is often seen across the industry.

Other factors that come into play:

- I assumed no wind; headwinds and most crosswinds will push the tipping point in favor of the aero bike while tailwinds will push the tipping point in favor of the climbing bike

- Increasing rider weight will push the tipping point in favor of the climbing bike and decreasing weight will push the tipping point in favor of the aero bike (roughly by 0.2% grade for every 10 kg in this example)

Marcel Keyser, Engineer With the Specialized Human Performance Team

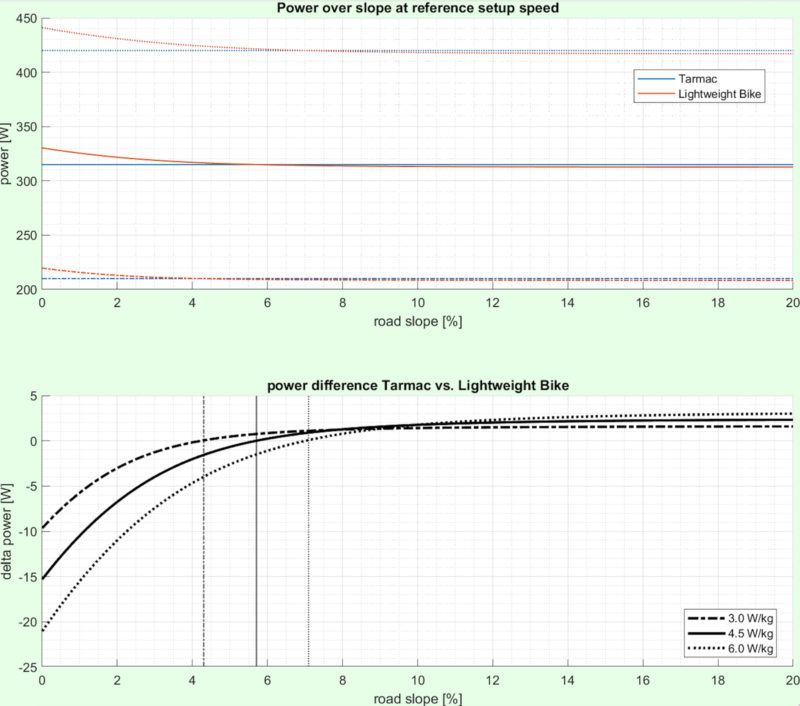

For the simulation, we created three “virtual” bikes — weight, CdA (coefficient of aerodynamic drag), and a consistent rolling resistance — and ran them in a number of scenarios. We used our Tarmac SL7, the Aethos, and then a “pure” aero bike based on what we know from many dedicated aero road platforms from a variety of manufacturers.

The rider has 70 kg + 1 kg of gear. Rolling resistance is similar to a nice Turbo tire.

| Virtual Bike | CdA | CdA Delta | Bike Weight |

| Tarmac | 0.2950 m² | 0 m² | 7.05 kg |

| “Pure” Aero | 0.2935 m² | – 0.0015 m² | 7.6 kg |

| Aethos (Lightweight) | 0.3120 m² | + 0.0170 m² | 6.45 kg |

Conclusions

A. General

- The stronger a rider is, the steeper the road needs to be to hit the break-even between aero and weight.

- Stronger riders work more against aero due to higher average speeds.

B. Tarmac SL7 vs. Aethos (Lightweight)

- Climbs need to be steeper than approximately 5% to see the advantage of the lower weight.

- It’s interesting to see how different rider speeds play a big role in when the Aethos versus the Tarmac choice delivers an advantage.

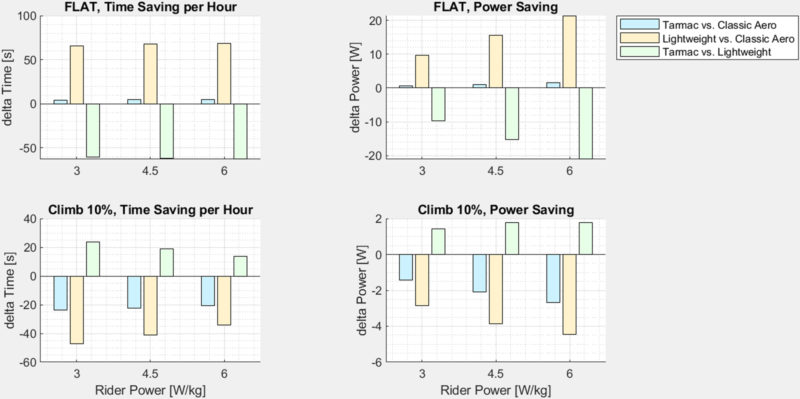

Based on 3 W/kg, 4.5 W/kg, and 6 W/kg, representing amateur, strong amateur, and pro riders, respectively — we know it starts to matter beyond 5% grade for all riders, but the big-time gaps don’t occur until steeper slopes, so we calculated the time delta (change) over an hour of riding a 10% slope on a Tarmac versus an Aethos for each of these riders. Essentially, how much faster the Aethos covers the distance that a Tarmac SL7 does in an hour. You’ll see that, and watts saved, in the below summary graphs.

- At 3 W/kg, the Aethos is 25 seconds ahead after an hour over the Tarmac SL7 on a 10% slope.

- At 4.5 W/kg, the Aethos is 19 seconds ahead after an hour over the Tarmac SL7 on a 10% slope.

- At 6 W/kg the Aethos is 14 seconds ahead after an hour over the Tarmac SL7 on a 10% slope.

It’s important to note that with today’s races, the aero advantage over an entire day and the rarity of any race with sustained 10% slopes, combined with the need to add ballast to make an Aethos UCI legal, make the Tarmac SL7 the undeniable race choice for our riders.

We did the Tarmac SL7 versus a “Classic” aero road bike for fun too. The results were pretty incredible. The Tarmac SL7 gives up almost nothing on the flats and gains 4X that time back on a climb.

C. Tarmac vs. “Classic” Aero Bike

- There is almost no disadvantage on FLAT road.

- The delta power plot shows approx. 1 W disadvantage on flat and 2 W advantage on climbs for the Tarmac. This sounds like 50%/100%.

- BUT! Look at the TIME savings per hour bar graphs in the summary plots above:

- The Tarmac loses 5 seconds in 1 hour on the FLAT and wins 20-25 seconds in 1 hour on a CLIMB versus the “Classic” Aero Bike.

- This delta is huge, validating the incredible combination of lightweight and aero that the Tarmac delivers.

Thank you again to Specialized Bicycles, Trek Bikes, Cervélo, and Cannondale for contributing to this feature.