If the recent silent freehub design we found is any indication, Shimano is looking at ways to reduce noise, friction and drag in some creative ways. And perhaps this chainring design, which we found in yet another patent application from the drivetrain giant, is even more creative despite its utter simplicity.

Want to reduce weight? Cut drag and friction? Easy, just remove every other tooth. But not just any teeth, only the narrow ones from a narrow/wide design. Which is even more odd coming from Shimano since they don’t currently offer a narrow/wide chainring, though they have patented shiftable narrow/wide ring designs. And, we’ve heard from one source (but can’t verify) that Mr. Shimano was the first to patent a narrow wide chainring design all the way back in 1978, albeit for agricultural purposes. Yes, you read that correctly: Shimano may have been the first to patent a narrow/wide chainring design, and they did it almost 40 years ago.

Here’s how this could work…

The patent application states the design could be used to reduce the weight of the chainring and reduce the likelihood of missed shifts. The weight savings is obvious, but there are a few tricks to save more than just the weight of the missing teeth. Images below show cut-outs on the teeth as an option, and the filing mentions a sandwiched design of using a hard candy shell (iron, titanium) over a lighter (alloy or resin) interior.

Beyond weight, the focus is on performance, with mention that fewer teeth could improve shifting performance. There’s not a deep dive into why or how it would improve shifting, and not all iterations are even designed to accommodate shifting. Figure 3 shows a non-shifting design with square edged tooth shapes.

The teeth are, however, shaped to facilitate the chain gliding on and off the teeth. But for shifting, the teeth get chamfers (222) on the leading and trailing edge, top to bottom. That’s shown in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6.

It’s particularly interesting that this seems to be the focus of the design. Specifically, the filing reads: “Further, the bicycle chain is less likely to fail to engage the sprocket teeth due to less number of the sprocket teeth in comparison with a conventional sprocket.” Perhaps this primarily refers making it easier for the chain to lift off of a ring and start towards the other one.

For settling onto the big ring when shifting up, there are a few additional features shown that either claim to or we suspect will aid in helping the chain settle into place. Fig.7 shows an intermediate tooth (317) that would be narrower than the others and designed to catch the inner chain links, and it would all be timed with pins to encourage the wide links to settle onto the wide teeth.

Fig. 11 shows a cutout, which they note can take any shape, at the base of the tooth intended to reduce shock by allowing it to flex (Imagine a fish’s tail. Not a dolphin, a fish.). We interpret this as shock from a chain shifting onto it under load.

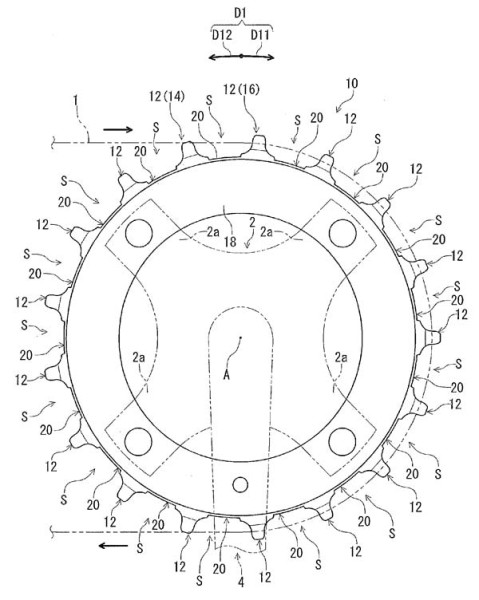

Switching back to what we presume are single ring applications found on so many modern mountain and cyclocross bikes, another iteration shows a support platform (960a) at the base of the tooth. The chain’s outer link plates would rest on it as it settles onto the tooth, providing additional stability. This could mean a proprietary chain-and-chainring design meant to work together. A recess (20, shown on all images) presumably allows a straighter path and plenty of mud clearance for the inner links.

So, could this work? Well, Shimano’s not known for putting out any product that hasn’t been dialed to near perfection. But, we reached out to several other chainring manufacturers to get their input.

Brendan from Wolf Tooth Components said “The narrow teeth definitely help. They’re less critical to chainring retention, but they do help, particularly on smaller chainrings where you have fewer teeth engaged at any given time. And they’re particularly more important on smaller chainrings for driving a load. Because smaller rings have fewer teeth engaged at any given point, each tooth is handling exponentially more load. So, the narrow teeth would improve chainring durability.”

I spoke with another brand that wished to remain anonymous but concurred, adding that it would also likely cause faster chain wear because only the outer (wider) chain links are being used, so they’re pulling double duty.

Regarding durability comparisons, most aftermarket narrow wide chainrings are machined from alloy, which wears faster. This includes virtually every aftermarket ring from Wolf Tooth, Race Face, OneUp, etc. Shimano’s high end chainrings’ teeth are hardened steel, titanium, or cold-forged aluminum, all of which are much more durable.

The patent application mentions multiple materials molded together, using steel or titanium for the outer tooth profiles (430, 434) for long term durability and an inner part (432) of the ring from either alloy or a resin material, the latter suggesting a carbon fiber or composite spider is in the works…similar to what’s used in their high end cassette cluster or XTR single chainrings.

That dual material layering could make this design durable enough, particularly if it’s reserved for road applications that don’t need as aggressive chain retention but could really benefit from reduced friction.

And that’s the missing part of the conversation. The patent filing has no mention of reduced friction, and friction creates drag and robs power. Fewer teeth theoretically mean less friction, and that could end up being the real benefit of such “toothless” designs. Add that to the new rear hub design we spotted and you could have a dramatically more efficient road transmission.

One concern discussed with a competing brand was chainline and derailment issues when the chain is on the upper or lower extremes of the cassette. The further from 0º the chain rolls onto the chainring, the larger the lateral displacement in relation to the wide teeth, which could lead to an increased likelihood of dropped chains.

Regardless, it’s a very interesting concept that shows how the venerable bicycle continues to evolve and advance.