If you’re looking for the fastest aero wheels in the world, keep your scanners peeled for pro triathlete Heather Jackson aboard her new Knight Composites carbon fiber hoops this year.

Who’s Knight Composites? Oh, only the new brand intent on making the fastest bicycle wheels ever. Considering the massive interest in improved aerodynamics leading the development cycle at major brands like Mavic, Reynolds and ENVE (among many, many more), that’s a tall order.

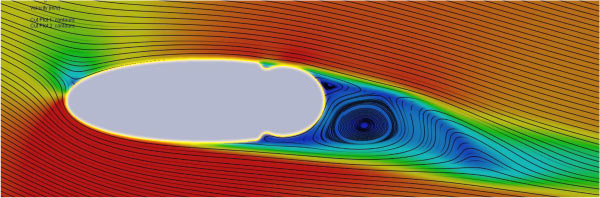

So, they began by looking at the wheel as part of the whole bike because, well, you can’t have one without the other. Their testing revealed that the trailing edge had a more profound impact on overall aerodynamics than the leading edge…and by “trailing edge”, they’re mainly talking about the back half of the front wheel. So, they developed what they call Trailing Edge Aerodynamic Manipulation (TEAM) Tech.

But first, they had to assemble their team…

After stints at Cobra making composite golf club shafts and starting Reynolds composites, Jim Pfeil was working at ENVE (when it was still EDGE) as operations manager and thought the company needed a global expert to come in and help the company grow. So Beverly Lucas interviewed and ended up becoming their global sales and marketing manager. She helped them make the name switch to ENVE to facilitate sales in other markets and have more ownership of their brand trademarks. She also helped start them down the road to developing an aero wheel by borrowing a little wind tunnel time from Felt while they were testing the DA tri bike. Then, while watching Grand Prix racing, she was inspired to reach out to that industry, which led to ENVE’s collaboration with Simon Smart.

From ENVE, Beverly moved to Australia work on different projects and learn that market, and Jim went on to work for Neilpryde. Fast forward a few years and she was back in Jim’s hometown of Bend, OR. They had coffee and decided that they should make an even faster wheel under a new brand. Thus, Knight Composites was born.

To round out the team, Kevin Quan (who’s worked on projects for Neilpryde, Diamondback, Parlee and others) is their lead engineer and company director. He oversees all designs and ensures their products are both accomplishing their own internal goals and meeting market demand.

Testing them under real world conditions will be Chris Horner, pictured above, and the rest of the Airgas Safeway development team, as well as pro triathlete Heather Jackson.

That’s a good team, but what makes the wheels special?

“Basically, every wheel company in the past has looked at the leading edge of the rim as the most important part of the structure,” said Lucas. “That’s why some of them have even gone into tire production, so they could control that front-most leading edge. What Quan did was look at the trailing edge, which we could control much better.”

The primary business of Quan’s studio thus far has been designing and engineering frames, the largest customer being Diamondback. They have a small wind tunnel in house that lets them test individual tubes, and it just so happens to fit a wheel. So, they started putting some of the best rated wheels in there to see what they could learn.

“(One brand) started with a two dimensional airfoil section onscreen, then converted to a full three-dimensional shape,” Quan said. “That let us get the full visualization of the airflow over a particular wheel section. We also reverse engineered a lot of our competitors’ products and threw things into CFD to figure out why others products were working or not.

“On the front half of the wheel, the tire really messes things up despite wheel engineers’ best efforts. What it comes down to is that the round shape of a tire just isn’t a good airfoil. When the air hits that tire, it’s going to separate, so you’d see more turbulence coming off the the front part of the wheel than on the rear. And that’s at even very low angles of yaw, around 5º wind angle.”

“We never saw a lot of drag reduction at the front of the wheel,” he continued. “But when we flipped it around, we saw much better airflow.

“A lot of companies try to create symmetrical airfoils, making the leading edge the same as the rear. That makes the leading and trailing edge of the rims rather blunt. But we put a lot heavier emphasis on how the air hits the back half of the rim. We wanted to ensure that when the air left the trailing edge of the front wheel that it didn’t mess up the air hitting the frame. When the downtube is behind the tire, the rim/tire/frame acts as one giant airfoil.”

That thinking is what sets Knight Composite’s designs apart from the rest. Think of the fork bisecting the wheel. Everything behind it is what’s creating most of the drag. On the trailing edge (back half) of the wheel, the tire plays a much less disruptive role, especially since the wind transitions immediately onto the downtube.

They’re using the same rim profile front and rear, though they’ll offer three different depths so you could run a deeper section rear if you want. As for aerodynamics improvements, though, Quan says you’re still getting the biggest bang for your buck by improving that trailing edge front transition into the frame. The rear wheel acts similarly, but plays a lesser role in overall aerodynamics. In most cases the front of the rear wheel is somewhat shielded by the seat tube, particularly on a TT/tri bike. But the exposed rear half of the wheel will perform better because of the design.

The other half of any aero wheel’s story is its stability in a cross wind, and Quan says their design also creates a much more stable wheel.

He says with almost any wheel, the air on the side facing the wind is going to remain attached. The trick is keeping the air attached on the other side of the rim, and that’s where stability comes in. Compared to many other aero rims, Knight’s profiles have a more of a gentle progression of shape from the front of the rim all the way to the tire.

“The wind hitting your body and your frame is going to try to push you to the side,” he says. “You’re still going to be blown sideways and the wheel can’t fix that. But, when the wind hits your wheel and fork and wants to wrench your steering, that’s where we can do something.

“The back half of the wheel has lift, and the front is pretty much stalled in anything past a 5º wind angle. Because of that, it wants to turn the handlebars into the wind, which helps keep you riding in a straight line.”

The end result for their 65mm depth wheels was about a 30g reduction in drag at 25-30mph across a wide range of crosswind angles from 0º all the way to 20º (tested front wheel only, corrected for atmosphere, etc.).

The line kicks off with three different rim depths: 35, 65 and 95 millimeters. Specs are:

Retail is $2,599 per set for the 35 and 65, and $2,899 for the 95mm, all with DT Swiss 240 hubs. They can also be built with DT 180 hubs, and they’re building the wheels with Aivee hubs for Horner’s team.

While Lucas’ former employer ENVE prides itself on making their carbon wheels domestically, she says they went to Taiwan because they found it to be a competitive advantage since they’re doing things a bit differently.

“There are some people out there that assume we’re going to Taiwan because it’s cheap,” she said, “but the factory we’re using, it’s not cheap at all. We wanted to make our wheels as strong and light as possible by using the same technologies at the same places that make the top Pro Tour level frames. We can honestly say we’re a third generation wheel company, using the best and latest technology and techniques to make wheels better and differently than anyone else.”

Quan expanded on that, adding “We use the same double tooling method that has an EPS foam mandrel on the inside and a metal mold on the outside. The same process as high end carbon bike frames.”

That higher compaction lets them use less material, which results in a rim that they say is about 20-30g lighter than the competition. Because there is less carbon needed on the walls, Quan puts a little extra material on the brake track to thicken them up to help better dissipate heat. He says their brake track is up to twice as thick as the competition at 3+ millimeters thick.

At the moment, they do not recommend running them tubeless. Quan says they’re talking with a major tire manufacturer, but the issue remains compatibility and the lack of a road tubeless standard. They have gone through the development process for tubeless mountain bike wheels, though…

WHAT’S NEXT?

“We’re starting with wheels and we’re sticking to what we know,” says Lucas. “We have clinchers now, and in late spring we’ll introduce tubulars. Around Sea Otter we should have our mountain bike wheels, and then eventually our disc brake wheels for cyclocross in time for the start of next season.

“Will we go into components in the future? Probably, but at the end of the day we didn’t want to make (a part) just to make a buck. I told Jim when we started, if it’s not going to be ours and be proprietary, I’m not interested. And that’s what we’ve done with the mountain bike wheels and the tubulars.”