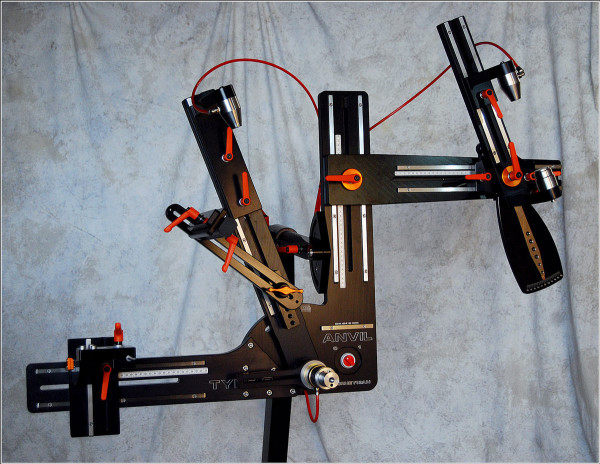

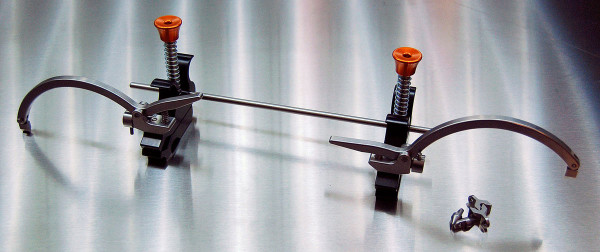

Don Ferris is so pervasive within the frame building community that many take for granted that he exists. His company, Anvil Bikeworks, develops and fabricates the fixtures that help build many of the bikes you’ll see at NAHBS this year. At this point, it is unusual to walk into a frame builder’s shop and not see something of his work.

But knowing how much the fans of the community enjoy the cult of personality, it is a crying shame that Don, due to his customer base of frame builders, is relegated to the background. He is one of the more dynamic members of the industry. Few others have gone from the wrong side of the law, to the Antarctic, to UBI, to giving up a successful career as an esteemed frame builder in order to build the tool that the community uses to do their jobs every day.

When editing, I enjoyed the story so much that I left it a little longer than the others because, hey, this is the internet…

BIKERUMOR: So you started out as a frame builder. But before that, you actually started welding really early – you grew up in a machine shop. Is that correct?

DON: Yeah, I grew up in a shop environment. Actually, I started welding when I was twelve. So by the time I was high school age, I was pretty far advanced as far as welding goes. It’s in my blood, I guess.

BIKERUMOR: Your dad is a machinist right?

DON: He is, yep. Was. Lifelong.

BIKERUMOR: Were you always into bikes?

DON: Yeah, I was always into bikes. You know, kids, growing up in the LA area, you’re always on your bikes. Cypress, California is where we were living. It was a lot more rural than it is today, obviously.

BIKERUMOR: Forgive me, but you’ve got a heck of an accent for LA.

DON: I moved away from California in I think the 3rd grade. We moved out of the LA area when I was younger, we moved to Gustine, CA, which is by Modesto/Merced. I think we left California when I was in the 3rd grade and we moved to Texas. It would have been the Fort Worth/Kennedale/Mansfield area.

BIKERUMOR: That’s an accent that’ll stick to you.

DON: I got out of Texas just as soon as I can, but you can’t ditch some things. I’ve lived in so many different places that it’s amazing that I have any kind of accent at all, or understandable. I just followed my dad around.

BIKERUMOR: What was he doing that he was moving around so much as a machinist?

DON: He had his own shop and when we left California, my dad went to Carnation Can Division. Back in those days, canning companies would build their own canning machines, so what he did is not horribly unlike what I do today, basically, designing tools and fixtures to build another product. Some time in there was an ugly divorce. My mother went one way; my dad and I went another.

My dad was an expert machinist. He’s got patents. He’s got all kinds of designs. When he left Carnation, which was about the time I got out of high school, I’d been on my own since I was about 17. He went and started his own shop up, started working with one of his old partners, a guy by the name of Bill Murphy, who owned ATS Machines, Saginaw Gears, some other machine shop type deals in California. My dad was doing development work for him. I use one of his chucks. He was doing tool holding, designing and developing tool holding chucks and stuff like that for lathes. He had his own shop, that’s what he did right up until the day he died. He was just an old school, old world machinist. There wasn’t anything he couldn’t do.

BIKERUMOR: So you finish off high school. You go off into the world. You join the military. Is that correct?

DON: Yeah, I mean, there are gaps of time in there. I wasn’t especially bright as a student, nor was I a good citizen back then in those days – on the business side of a few detention centers, you might call ‘em. Jails. In my defense, I’d never stayed in any school too long. I was going to high school in Wisconsin. I didn’t want to leave and start school some place else my senior year, and my Dad moved to Missouri and I wouldn’t go. We’d been having typical father/son type shit, so we came to an agreement that maybe I should leave. And so I did. He moved to Missouri and I got legally emancipated.

It was interesting. I kept going to school, but I was working full time. My last day of school was right after my 17th birthday. I thought I wanted to be a car mechanic. I was working at a machine shop at night. And I got to where I had to leave Wisconsin in a hurry…

BIKERUMOR: No kidding.

DON: You know how it is when you’re young like that, and you have no parents around. I went to school in Oconomowoc. We weren’t far from Milwaukee, and we weren’t far from Chicago. That’s a whole other story. But when I got back out West, I took up welding again, and I was doing alright. In the early ‘80’s, the Reagan recession hit and the bottom fell out of everything. Heavy industry in Texas – all the big jobs dried up in the Reagan recession. And my past was haunting me, every time it seemed like I turned around I was having to revisit past issues.

So the way that it goes down is that I was in jail in Cleburne County, Texas, and my sister came down there and bailed me out. Bailed me out and then left me there. Cleburne County was a dry county. I was about 25-30 miles from home. Didn’t have anybody I could call to come and get me.

BIKERUMOR: Long walk?

DON: So I started walking out of Claiborne and I passed the enlistment office. You know, they had in those days, Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine corps, they would always be together, just in one little building. You just went in to any door you were interested in.

BIKERUMOR: So you could shop?

DON: Yeah. My dad always told me, he was ex-military, he always told me to not go in the Army. My dad was a Green Beret in the Army, Special Forces before Vietnam. Always told me never go in the Army, whatever you do if you go in the service, go in the Air Force. And so I went in the Air Force recruiter and they were, “No, you have a police record.” I went to the Marine Corps, they said, “Nah. It’s a few good men, that doesn’t mean people who just got out of jail with a police record.” And I was all, “This was victimless stuff. This was rowdy, drinking, that kind of debauchery.” I didn’t want to be in the Navy because I didn’t want to be a squid.

So in front of the Army recruiters’ office there was a chopper. I was like, “Well, this has potential.” I walk in there, and this guy had the longest hair of any guy I’d ever seen in the military. I told him what my deal was and what had happened to me and what I was looking at. “Oh man, that ain’t no problem. We’re going to get this squared away.” Great guy. Gave me a ride home. It took awhile, but I finally got cleared depositions on everything. It took about six months, but by the time I got everything done, he was true to his word. I went into the Army and just never looked back. It was exactly what I needed for me, I wouldn’t recommend it for everybody. But for me at that time in my history and for my life, I’ve never had so much fun.

BIKERUMOR: What were you doing in the Army?

DON: Well, I went in and joined to be special forces, so Green Beret. You could sign up and you wouldn’t be Green Beret – you would go through phase training to get there. I got to basic training, got the AIT, got to jump school to be a paratrooper, and they called me in the first sergeant’s office and said they couldn’t honor my contract anymore because you could not allow civilians to get attached to a Special Forces unit. That’s the way it was up until I think 9-11. So I transferred over, eventually became an Airborne Ranger.

When it came to my first enlistment, which was a four year enlistment, I signed up for what was called the BEAR program. Once you got done with your training, you’d reenlist with your new military occupational specialty, and if it was a BEAR program MOS, it had huge reenlistment bonuses. But there were too many people. I was bumped out based on how long I’d been in.

So I got bumped out and my wife at that time told me if I reenlisted that she would divorce me. And I still cared.

BIKERUMOR: Your “wife at that time…”

DON: So I got out, and they let you get out and stay out, it’s like a month, two months, three months. You go out there, play around, live your life a little bit. And if you come back in, you get a mulligan, you get right back in where you left off. And since I couldn’t get into the BEAR program, my options were pretty limited.

I got out, decided, “Well, shit, if I re-enlist, she’s gonna divorce me and I’ve got a kid.” She’d already left and separated, moved back to Texas. So I went down to Texas and I knew I had that 30 day or 60 day deal in my back pocket, so I had a backup plan – very important to have a backup plan.

So I was sitting there and I pick up the Dallas Morning Newspaper, when people bought newspapers, and they had this big ad in there from a company called Holmes and Arbor. When I was in the Middle East, Holmes and Arbor was a contractor that ran the camps in the Sinai Peninsula, behind the scenes for the military. I called them up and they were looking for ex-military folks with secret, top secret security clearances.

They were looking for folks just like me. So I called them up, talked to this guy named Pat Haggerty, he’s like, “Well, I’m going to come out to Dallas. You come out at 9 o’clock and we’ll see what we can come up with.” I was still basically in the military. I drove out there and I brushed this guy in the lobby and he had two cups of coffee and his eyes looked like two piss holes in the snow. He walked right by me. Got in the elevator together, starts walking down the hall. I’m looking at room numbers. Turns out to be him.

“You must be Don.”

“You must be Pat.”

“Hold these coffees.”

And he takes me in there, we talk for awhile. He offers me a job.

Next thing I know, I’m working the US Embassy in Mexico City. We were doing construction. I went to work welding, iron working, pipefitting. And so I worked down there for a year and a half. Went from that job to another outfit working in N’Djamena, Chad. It was right after the Toyota War, and so the US embassy there in N’Djamena had been sacked, so I went to work at the US embassy in N’Djamena. I get back to the states. By now, I’m divorced. My wife hates me. Pretty normal affair really. So I come back to the states and I know Pat really well. Pat was always talking about how he used to used to work on the ice for Holmes and Arbor, and they had the contract to do construction, logistics, maintenance stuff at McMurdo, South Pole, Palmer stations in the 70’s.

Pat says, “Come to Denver, I have a job in the office for you in Denver for the ASA.”

And so, I was like, “Yeah, you know, I’d like to do that, but -”

I had a two year contract to live behind the Iron Curtain and live in Pall, Belgium and I really wanted to do that because you’d get to go to Russia and Czechoslovakia. So I came to Denver, and I sat in the office, and they sent me to an intermediate DOS class – I couldn’t even spell computer. This was 1989, 1990, I guess. And then my deployment for this other job I was lined up for got delayed.

So he was like, “Come down to the ice and we’ll get you familiarized. You can work one season, then you can go on your deployment.”

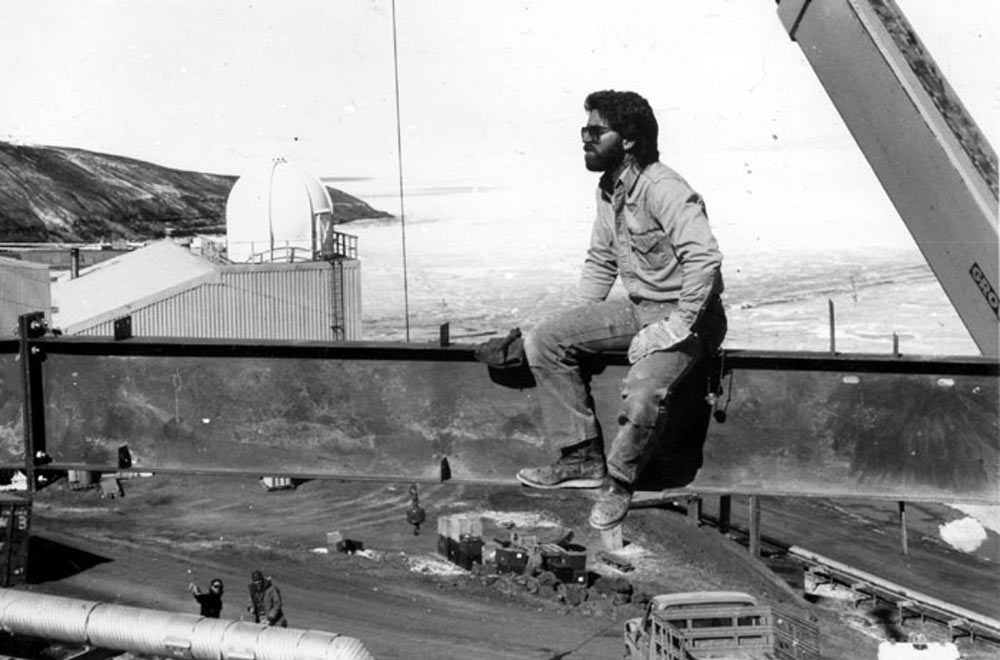

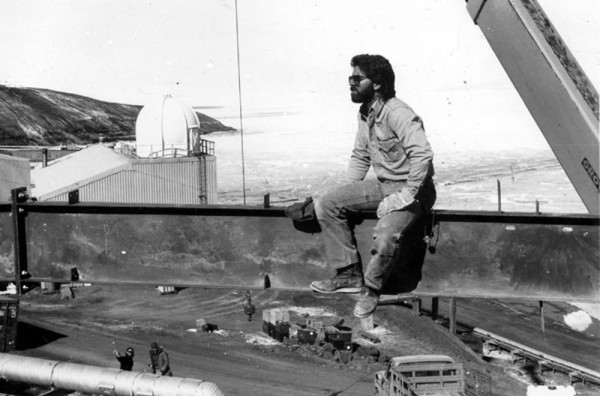

So I left Chad, it was 120 degrees. I walk out on Williams Field, Antarctica and was 50 below zero.

BIKERUMOR: I… I can’t even imagine the acclimation!

DON: You know, it was a life of adventure. The one thing I really liked from being in the military is that your situation was always fluid and everything was always changing. You might be in garrison one day, and then in Egypt the next. And then living and working overseas – when you come back to the US, everything kind of slows down.

BIKERUMOR: You get fidgety.

DON: Yeah. So I went down there and worked that summer in McMurdo and then I finished the projects I was in charge of. I’d been hired as a construction coordinator, I ended up finishing up my projects and I was getting ready to leave to go to Belgium for this new job.

Before I go, Haggerty tells me, “I want you to go to South Pole to get a feel for the place, we’re going to be building down there. Go down there, walk around a little bit, see what it’s like.”

I say “Pat, I can’t do it. I gotta get out of here.”

“If you don’t go, I’ll send you home and you won’t get your completion bonus.”

So I go to South pole and the weather comes in and I get stuck there. I had to call on the radio to my new employer that I was stuck – it was almost like they didn’t believe me.

“I’m stuck at South pole. I’m gonna be a little late.”

“Well you’re going to have to leave at the next deployment schedule.”

I was pretty pissed off. And so this guy – I’m sitting next to this guy on a C1-30 at the south pole, he’s like, “You’re that guy who built the fire protection system under McMurdo.”

“Yeah, that was my project.”

“What are you doing at South Pole?”

“I don’t know. No goddamned reason. Now I got a job in the real world I’m late for.” Turns out the guy is the vice president for the company. Jim Chambers, turns out to be VP of ASA. That was the wrong thing to say to that cat. He laughed it off when I was talking to him but Haggerty got in trouble for it.

I became construction manager in 1993 for all three stations. In 1993 I wintered over as a station manager in McMurdo. After I finished my winter over in McMurdo I became Senior Manager for South Pole and Palmer stations. Basically, I had operational oversight for all three United States Antarctic stations. And I did that right up until 1998.

BIKERUMOR: Wow, for five years you were doing that?

DON: The longest time I spent down there was 16 months straight. You know, as I got further and further up the food chain, and in charge, I got less and less happy. That’s the way things go. At first, it’s a big fun adventure. You’re doing shit. You’re being hardcore. And eventually you’re polishing the seat and all you’re doing is signing shit all day long.

BIKERUMOR: And it’s routine.

DON: Yeah, the people ruin it for you. You’d think that in the Antarctic you’d have a different breed of people, and you do in many respects, but you have the same problems you have anywhere in corporate America.

It got to the point where I had less and less patience for my job, and less and less patience for people’s bullshit – it’s a problem I’ve had my whole life. So I quit. By this time, I was married to Jill, my last wife.

BIKERUMOR: That’s smart terminology right there.

DON: I wish I had met her sooner. We’re just a really really good match and always have been.

So I called her up, and I said, “Guess what I did today?”

“You quit your job.”

“I did. I quit my job.”

“What are you gonna do now?”

“I think I’m gonna go to UBI and take a frame building class.”

BIKERUMOR: No shit! That’s amazing.

DON: When I quit my job I loaded up my bike in my truck and went to Moab. “Yeah, this is really cool just hanging out in the desert trying to get my mind right.” It’s really funny, I had at some point prior to this, I had picked up a magazine and it was a cycling magazine. At the very back end of it, they would do a custom frame builder article or interview. And I already knew a couple custom frame builders by this time because I was so into cycling, and I kind of left all that out.

BIKERUMOR: Yeah, I noticed that. We really haven’t talked about bikes so far.

DON: I had bikes. And I can tell you a funny story about that because Antarctica had a lot to do with it. What happened in 1992-93, they had a problem with shipping due to fuel resupply and so the stations had a fuel shortage. They were running out of gasoline. You had to walk everywhere and you couldn’t drive anymore. I knew I had seen a bike sitting underneath the MEC, Mechanical Equipment Center, it belonged to a man named Kirk Kyoto.

I asked Kirk, “Hey man, can I use that bike?”

“Well, that’s my bike, but yeah. I don’t ride it.” And it was a bike on the ice at McMurdo. So I started riding that bike around.

BIKERUMOR: Was there anything special about the bike for that environment?

DON: No, no. Piece of shit mountain bike. Probably been down there ten years already.

BIKERUMOR: Bet you were glad to have it.

DON: Hell yeah! It was way better than walking from one end of the station to the other. So I was riding again, now. Until the next year when we got off the ice for that year, I talked to Eric Chang, who was the head officer of programs for the National Science Foundation. And Eric was also a cyclist. I said “You know what we gotta do is we keep on this curb of not driving vehicles around McMurdo by riding bikes.” It’s at the foot of the southernmost active volcano in the world. The hills tend to be steep and long and everything is uphill from where you’re going. So we did a test program. There were already some walking trails set up. So I took Eric Chang on a mountain bike ride around McMurdo and he authorized us to buy five mountain bikes as a test program. So we did. We bought five Diamondbacks here in Denver.

BIKERUMOR: When a Diamondback was a Diamondback.

DON: Yeah, when a Diamondback was a Diamondback. This was the early 90’s. So yeah, we took bikes down there as a test program, people started riding them. Now they have fat bikes and everything else, but back then it was a big deal. It was hard to get people involved in it. We had a cycling club down there called the McMurdo Mountain Bike and Drinking Organization. But that whole thing down there really reignited my passion for cycling.

So when I got of the ice that year, I did a big bike tour around New Zealand. When you get off the ice in February, it’s still good summer weather in the south.

BIKERUMOR: And New Zealand is gorgeous.

DON: Oh yeah. You know, everything just kind of took over, like anything cycling. The more and more you do it, the deeper you get into it, the more it kind of takes over your life. So I was entertaining these thoughts anyways and Todd Shusterman of da Vinci Designs, and John Hargadon – I would go in there and watch those guys building bikes and I went “I can do that.” ‘Cause everybody when they look at frame building assumes that they can do it. It’s a lot harder than it looks. I had that crawling around in the back of my mind. And then when I was in Moab, Road Bike Review – I open it to the back page and there’s Margo Conover, the force behind Luna Cycles. She doesn’t do it anymore. I was looking at that and was like, “Man, that’s gotta be the coolest thing ever. I gotta do that.”

I started looking at it and I called UBI because they had a frame building class and they were in Ashland Oregon. They had a class starting in five days. And I was like, “I’ll be there, man.” Loaded up my Grand Wagoneer with all my camping gear and drove up there.

I met Jim Kish, he was the class instructor. Met Mike DeSalvo – was out there at the same time. Ron Sutphin. We all kind of became friends, went riding together and stuff. Going to UBI was probably the most fun I’ve ever had in my life over a two week period. I went out there, I felt really clear-headed about the whole thing. I felt like I was making the right decision. I camped out at Emigrant Lake, right outside of Ashland. It was wintertime and so there was nobody else there. It was just me. I would ride down, and take a frame building class, and ride back. I just kind of rediscovered myself, and maybe reinvented myself, I don’t know. But yeah, it was just a life-changing event.

I tell everybody to go to a frame building class before they buy tools from us because everybody makes the assumption that frame building is really an easy thing to do. It’s probably one of the more difficult things to do from a fabrication point of view, and do it well. Obviously, you can go to UBI and hack together a frame in two weeks. But really, it’s much harder than it seems to do well. You can tell when you get down to the last few days that the stress of it starts to take the toll on students. And, I mean, grown men crying because you’re so stressed because it’s not going well. What UBI excels at in my opinion is one, you’re not a frame builder when you come out of there, what you are is you’ve been exposed to the process and you have seen a frame built. And you really have to build on that immediately because it’s really human nature to forget a lot of the subtleties that you witnessed.

You’re kind of a frame builder-shaped object when you get out of there. What’s really important though is when you finish UBI, you’ll know if you ever want to build another frame again. And you may not. I think the vast majority don’t ever build another frame again. They go in with these aspirations and then they realize how hard it is and how hard it is to do well. The welding – it’s a little demoralizing.

It’s rare that you do many things that require that kind of three dimensional coordination. It’s one thing to walk and chew gum. But when you have to use three of your extremities at different rates at the same time, you have your torch hand, you have your filler metal hand, and you got your foot pedal – it can be hard for people to get that coordinated. There’s just a lot of things going on there. And when someone comes into a two-week class and they’ve never TIG welded before, it rarely results in good results.

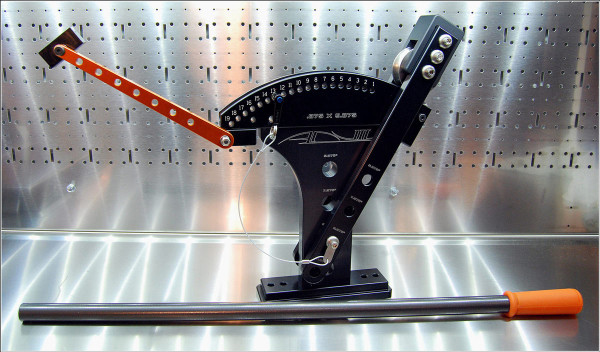

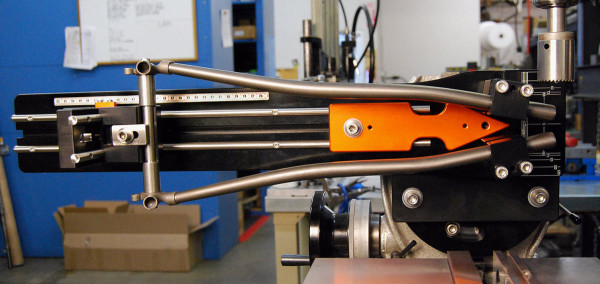

But when I left UBI, because of my previous welding fabrication background, I was more excited. My wife wasn’t too excited. “You just quit a six-figure a year job.” We’d talked for so long about me leaving the program that it was a big deal, but it wasn’t a big deal. The first thing I did when I got done was I drove out to my dad’s place because he still had a shop. Sketched out some ideas that I had for making frame fixtures because you couldn’t really… I mean there were some frame fixtures that you could buy, but it wasn’t like today. They were still pretty pointed towards lugged building or fillet brazing. I just wanted to make my own stuff.

BIKERUMOR: Wow. So you came back from UBI and you were thinking about fixtures right away.

DON: You had to have a fixture to start building frames.

BIKERUMOR: I mean you, you particularly – different things happen when you leave UBI or whatever apprenticeship. You weren’t just thinking about bikes, you were thinking about both fixtures AND bikes.

DON: Yeah, in order to make my first bike, I needed to make the tools to make them with.

BIKERUMOR: And you right off the bat didn’t like what was out there?

DON: I don’t want to get into casting stones. Then, the Bike Machinery Hydra was $11,000-13,000. And they were designed during the lug era. The concepts were the same. The joinery process was different and some of the demands were different. Other fixtures – from using them, they seemed clunky to me. But they were a product of that day. This was 17 years ago.

BIKERUMOR: People don’t necessarily do things just because everything else sucks, you know. You have to respect your competition, which you clearly do. There was a necessity in your mind. You recognized the necessity for yourself for a tool that you could make, so you started sketching.

DON: That’s exactly – you say it better than I do. Basically what happened was “I’m going to put this thing together. This is what I think I need to have.” So that’s the way I approached it. And then I drew some stuff out and then I started talking to my dad.

BIKERUMOR: You were friends again by this point?

DON: Oh yeah. The day I went into the service, my dad thought the sun rose and shone on me once again.

BIKERUMOR: In Denver?

DON: No, this was New Mexico. You know, we just kinda figured out what I wanted to do and we made the first fixture that I had right there in the shop. I think I stayed down there for about a week. We made all the fixtures I thought I would need. It was a re-familiarization with me and I was surprised how much I had learned from my dad just through osmosis. I worked for my Dad’s shop but I hated it. I didn’t like machining. It was just, you know, it just seemed boring. And I didn’t really have any appreciation for it because I didn’t understand all that was involved.

I came back to Denver, brought my new tools with me, set them up in the garage at my house, and started building frames. And actually, it went really well right from the get go.

BIKERUMOR: I like how hard you talk about how hard it is for everybody else.

DON: I understand the realities of the craft and the trade and I had a huge advantage going into it because of my background. That’s a lot different than a lot of guys who have never been in the fabrication industry who really like bikes and decide to make bikes. It’s a giant step for them. For me, it was more a lateral move. And there was still tons to learn. I went into it “Oh shit, I’ve done way harder. I’ve done nuclear welds. I’m a certified welding instructor. I’m a blah blah blah. I can do this in my sleep.” But when you start welding together tubes that are less than 30 thousandths thick, and sometimes down to 15 or 16 thousandths thick with the expectation for the industry has for weld quality and appearance, that’s a whole other circus right there. That’s a whole different show.

If I would have been to UBI without my background, I would have been one of those guys crying on the – not really, I don’t cry. I don’t have feelings. But if I had tear ducts, I would have been crying on the last day if I didn’t already have ten years of experience. I already had a lot of experience going into it. I understood the process. And I understood tooling. And I understood fabrication. And I understood the properties of materials which is really really important. What materials do when you heat them and cool them.

BIKERUMOR: People don’t get that, even after a time building. It’s crazy.

DON: What’s crazy is people have done it for 20 years and don’t understand it. There’s a lot of one trick ponies out there.

BIKERUMOR: And you interface with all of them.

DON: A lot of them I do. There’s a few I don’t… You can’t be this opinionated and have everyone love you.

BIKERUMOR: Oh, I know. It’s okay.

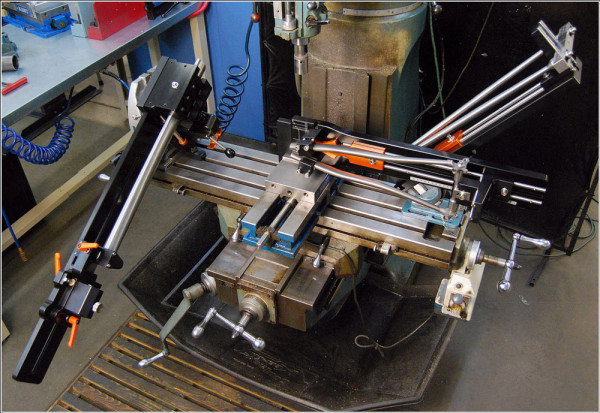

DON: Yeah, so what happened was I went to a bike show. I think it was one of the early VeloSwaps. VeloSwap would bring people in from all around Colorado and the surrounding states. All the big racing teams would be in there getting rid of their old gear. Shops would be dumping stock. It was big. I had a booth. I thought, “This’ll be a great place for people to learn about me as a new frame builder.” I had four or five frames that I had built and I was using all my frame building tools as my backdrops.

My bike frames could have been made out of Plexiglas

Every builder that was there at my booth. “Where did you get this? Where did you get that?” All these frame builders, yeah. And I sold my first frame fixture at that show. When I left there, when I left that show, I was like, “Man, there’s a lot of people who want frame building tools.” And in my naivete, I was like, “You know what I could do, I could build bikes in the summertime and tools in the wintertime when demand slows down.” I didn’t understand the bike industry.

I started making fixtures the way my dad made fixtures on manual machines, and people were buying them. “This is really odd that people want this shit.” I think my first batch of frame fixtures, I built ten of them. They were these huge things, they were taking hours and hours, but they would sell just as fast as I could make them. My bikes were going out the door like crazy. And I began to understand that I couldn’t schedule worth a shit – and I was a construction manager whose job was all about scheduling.

That’s the first lesson you learn, and when I give seminars or whatever, there’s this idealized, romanticized vision of what people have of frame builders, and then there is reality. The reality is that you are in the critical path of every activity that you have. When the phone rings, you are the labor allocated to answer the phone. If there is a knock at the door, you are the labor allocated to answer the door. Packing it up, dealing with it, brazing it on – you are on the critical path.

The old thing about frame builders that, “They tell you six months, gonna take a year. They tell you three months, it takes six months. They are always late.” There are builders who don’t do that, but there are a lot of ‘em who do. And you’ll start to learn that more customers, and I can feel myself slipping into a rant that’s going to piss a lot of builders off.

There is a basic economic lesson to be learned here. One is, there this whole thing about frame builders and their wait list. And frankly, it’s total bullshit. If you have a ten year wait list, you don’t understand economics. Boom. If your demand is so high and the turnaround period is so far out there then you need to raise your prices and cut down demand until you find your own angle of repose. It’s really hard for frame builders to get their mind around that concept.

Early on in the internet period, early 2000’s late 90’s, wait lists became a dick measuring contest. It truly did. You’d have some guy “My wait list is 3 years long.” “Well mine’s 5.” Well mine’s 9!”

BIKERUMOR: “Mine’s 30 years!”

DON: It doesn’t even make sense at a certain point. If your demand is so high that you can’t meet demand, then you raise your price. If your wait list is a year, I’m not talking to you. If you’re charging x amount per frame and people are lined up out the door and around the block three times, you’re not charging enough. And that goes hand in hand with people pounding the drum that you can’t make money frame building. If you look at the numbers, I mean, we live in the age of the five thousand dollar wheelset. When you start off, you’re going to start off low because the one thing you can offer the public within your first year or so is low cost. You can’t offer them experience. You can’t offer exclusivity. You can’t offer them the cult of personality. You can’t offer them a lot of these things that a lot of custom frame customers are looking for. So you hit them on price.

When you’ve got a guy who’s done this for fifteen years, does this for his full-time job. His job is building frames. If he’s doing one frame a week, the math is so simple that once you figure out overhead and materials, you have to charge enough to match your workload plus give you the quality of life that you need to pay your expenses and maybe retire. Hard to do. Hard to do. But people are doing it. And that’s the one thing that people talk about. “There are too many frame builders.” Maybe, but there are never too many good frame builders.

I like Ron Sutphin’s comment when I asked him, “Can you really make a living at this?” “There’s always room for one more.” And that’s really the case.

But what you’ll see is some established frame builders trying to discourage some younger frame builders. Without putting too fine a point on it, there is a reason why that occurs. I’m in the bike industry and I know it happens in the bike industry, but I know it happens elsewhere.

BIKERUMOR: Some people don’t like competition.

DON: Boom. It’s about managing the competition. It’s tough. I’m not saying it’s not. You have to have your shit together. You gotta bring your ‘A’ game every day. And you’re only as good as the last son of a bitch who said something shitty about you on the internet. You can’t have bad days, at least not public bad days. If you have a bad day, you want to stay on top of it with your customers.

And there are guys out there that excel at doing it. You look at guys named Carl Strong, the pro’s pro. Kent Erikson and Steve Potts. They’ve figured out that the way you don’t have problems is that you deal with it up front. If you tell your customer three months, it’s there in three months.

BIKERUMOR: Or two and a half.

DON: Under promise, over deliver. When I started until 2004, I was learning that I was in the critical path of everything. But now I had two major products. I was providing custom frames for custom frame customers and I was making fixtures for frame builders. I was inexcusably late. I had way more work than I could really deal with.

BIKERUMOR: What did you enjoy doing more?

DON: If you’d ask me when I was building frames, I would have told you frame fixtures. If you’d ask me when I was building frame fixtures I would tell you building frames. But over the period of time where I transitioned to building frame fixtures full time, I could read the writing on the wall but I didn’t want to admit it.

BIKERUMOR: When did you know?

DON: There came a point early on where “If I’m gonna keep doing this, I can’t keep doing it on the manual machines, I have to get a CNC.” So I got my first CNC mill. And then I hired people. But I just kept moving farther and farther behind. I didn’t want to lose my identity so hard fought and won as a frame builder. I didn’t want to let that go.

Finally, I had to make a decision that I had to do one or the other. My wife and I talked about it and I had, by this time in 2004, I had a pretty sizable investment in the tooling side of the business. Thousands and thousands of dollars. And that’s how it was, I was too far down that road to go back. And I had too many customers and too much product out there to turn my back on it, where anyone who didn’t get a custom frame just wouldn’t get one.

I made the announcement that I was no longer making custom frames, that I was moving to tooling full time. And I fought the stigma for a long time, “why would I buy frame fixtures from Don when he’s my competitor with custom frames.”

BIKERUMOR: Huh, I didn’t even think about that.

DON: I had some interesting conversations with people about all that. So I gave it all up. And we went to building frame tooling full time in 2004, 2005. And It’s been great ever since. I don’t have any way of verifying it, but as far as I know, certainly in sales volume and what not, we are the largest manufacturer of frame building tools in the US.

BIKERUMOR: It’s rare for me when traveling to a frame shop to not see one of yours in the shop. It’s the Journeyman or the Feng Shui, your IS tool.

DON: Yeah. Yeah, we have a little game we play here at the shop when we see frame builder interviews to see how many Anvil fixtures we can see in the background. We joke about it here, but I’ve built more frame fixtures than some builders have built frames. Frame fixtures, just frame fixtures, I’m closing in on a thousand of them. That’s a lot of frame fixtures. People ask “Where do they go?” Shit, they go everywhere. All over Europe. All over the US. I’ve shipped fixtures to Antarctica. Specialized uses one of our fixtures at their prototyping facility. We’re still a very small shop. This whole thing fits within four thousand square foot. There’s four of us.

BIKERUMOR: What’s it like to have had this kind of impact? To be this pervasive entity within this industry that you love – it is a very interesting relationship to have with it. You’re everywhere!

DON: It’s interesting. Yeah, I don’t even know how to address it. It’s kind of like always being the bridesmaid, never being the bride. You’re kind of like a wall flower. You’re kind back in the corner, watching what’s going on out on the dance floor. And with my personality and ego – I struggle with that sometimes.

Our customers have changed, I guess that’s the biggest thing. I get a little wistful about that. I probably should be careful… used to be, and I’ve said this before so I can repeat it, but it used to be when we made a tool, they would get that tool and they would go, “Oh my god, you freaking rock. You walk on water. I have done this for so long with such a piece of shit tool, it’s just better!” And you can send that exact same tool to someone who has been frame building for six minutes and he’ll go, “How come it doesn’t do this? How come it doesn’t do that? How come it doesn’t sweep up after me when I’m done?” And you kind of sit back and go, “Ehhh.” I’m not saying that they are all like that, but we get our fair share.

BIKERUMOR: You’ve become the default when you used to be the white knight, you know?

DON: It’s kind of that way. No one appreciates a refrigerator until their meat is rotting. We’re kind of like the… Roomba. Occasionally we jut out from underneath the chest of drawers or you see us skittering across the room. And then you forget that we exist.

BIKERUMOR: So the last thing I’m asking everybody: there’s a kid walking around the show at NAHBS. The kid wants to grow up to be the next Don Ferris. What advice do you give?

DON: Stay in school.