Out on the front range of Colorado, there is a thriving pocket of builders who specialize in curvy, Klunker-derived mountain bikes. There is Chris Sulfrain at REEB, Cjell Money, Burnsey of Oddity, and Todd Heath of Moonmen. The bikes coming out of this crew are marked by their complex, three-dimensional forms and enthusiastic experimentation using new standards and technologies.

The Godfather to this talented and creative crew is the one and only James Bleakley, owner of Black Sheep Bikes and all-around nice guy. All of the aforementioned builders have apprenticed at his shop at one time or another (along with that talented up-and-comer, Corbin Brady). When I stopped by his shop, we talked about how he came into his distinctive, windy style as well as his building philosophy.

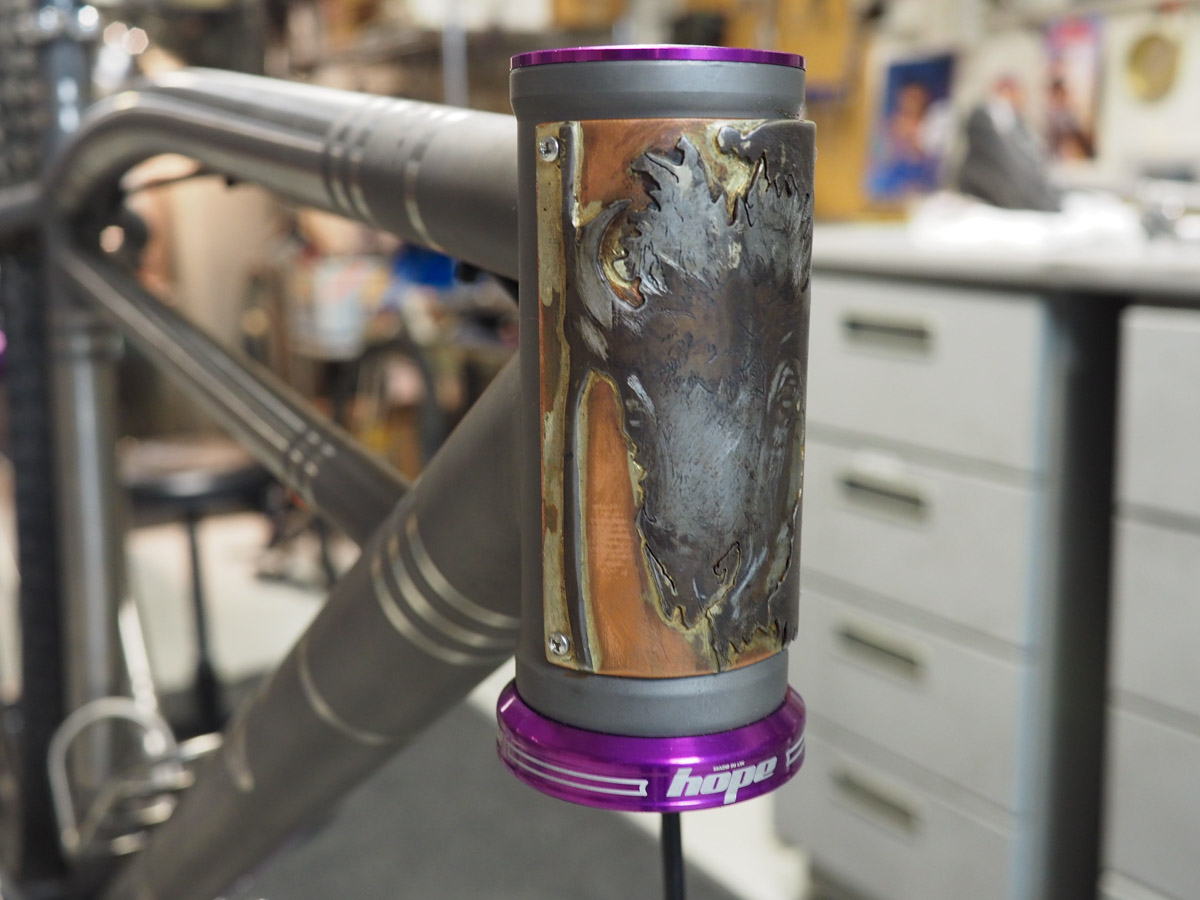

Also, for all those Black Sheep fans out there, James has treated us to a sneak peek of the Deathsplosion he’ll be showing in Salt Lake City.

BIKERUMOR: You started out in BMX. Is that how you got hooked on bicycling?

JAMES: Yeah. As a kid, it did. I was pulling bikes apart and transforming them into other things as a kid. Old Schwinn Stingrays and putting riser bars on them before I got my first true BMX bike. God, that was in Kentucky. I moved to Boulder when I was 13 and my BMX became my ticket to freedom.

Yeah, god, it’s been a long time. That was 32 years ago that I moved to Colorado.

BIKERUMOR: You moved to Boulder from Kentucky. There were other people around. You didn’t have to make your own fun.

JAMES: Right. Exactly. The bike became my transportation. I could get around and see places and wasn’t relying on my parents to get around. It was really awesome to have that kind of freedom. It was really eye opening to go from rural Kentucky to downtown Boulder. Things that I never even suspected existed were at my fingertips.

BIKERUMOR: It was a very different Boulder at the time.

JAMES: It was pre-yuppie. There were local hippies and that was about it. It was a nice place to go to junior high school and high school. I came up here to go to college and I’ve been here ever since. What I like about this town is that it has a lot more of a real feel to it. It’s not so one dimensional. You’ve got some ethnic diversity with a large hispanic population. A large Ag population.

BIKERUMOR: Then you fell into mountain bikes.

JAMES: It was the same thing. There was a lot of freedom to be had in college on a mountain bike. It was a great way to explore the area. A bunch of trails were being created.

That’s when I started at Boulder Bikes. They were making full suspension mountain bikes. I was coming off a hardtail. Who needs suspension? But then I started riding and like, oh wow, all of a sudden going faster than I’ve ever gone. It was a blast too. That bike was heavier, but in a lot of ways it was a lot more efficient. I’ve kind of come full circle a couple years ago and started riding rigid again and, in fact, single speed for ten years now- fat bike for the last four or five. If you had told me in the early 90’s what I’d be riding today, I would have told you you’re crazy. It’s just a fun bike to ride.

BIKERUMOR: That’s awesome. Boulder Bikes, is it still around?

JAMES: Now Boulder Bikes is a different company. It is owned by Mike Kone who does more rando stuff. You know the Rene Herse line? All that really traditional rando stuff. It’s a completely different thing. The Boulder Bikes I worked in- here is one from the early 90’s. Elevated pivot shock in the top tube. I built that thing in probably ’92 or ’93. And then, after I quit, I started tinkering around and these are a couple things that I built.

It was kind of early on in terms of culture. They had just made the first Rock Shox and we were building bikes. It was really ripe. It was just starting to take off. People were exploring suspension and trying to figure out where you put the pivot and how much travel you could get.

BIKERUMOR: Well, people will always be screwing with that.

JAMES: That’s what’s hard about it as a builder. Most of the bikes I build aren’t for suspension. It’s too time intensive to try to keep up on all the design work.

BIKERUMOR: The fashion of it!

JAMES: Yeah, right? It’s almost fickle. It could be a great bike, but if it isn’t seen as new, it’s old school. As much as I harp on road bikers for being stuck in tradition, the exact opposite is true in terms of full suspension bikes. It has to be a new design every year or two or it just isn’t contemporary enough.

You look at how many dropout changes there have been in the past three years.

BIKERUMOR: Oh, and Boost. I remember when I was designing and they gave us the Boost preview, and I was like, “… fuck.”

JAMES: Right! Just when I thought I’d bought my last wheelset for a few years.

BIKERUMOR: Something I’m curious about is: it isn’t like the Midwest where you can get a Bridgeport, cheap and easy peasy. How were you equipped down here? Yeti used to have a difficult time back in the day, but you’re right on the front range. I assume it would be better.

JAMES: At that time, when Yeti was in Durango… I started building tandems for a company in the early 2000’s…

BIKERUMOR: DaVinci?

JAMES: Yeah. That guy had his finger on the pulse of all that kind of equipment. A guy named Mike Barry who did a lot of machining for Avid was around. Another guy locally had a ton of used equipment. I had no problem falling into either the horizontal mill and the lathe that I have now. I went Craigslist to find the other vertical mill. It’s been super easy to get that stuff and we’re only a couple miles from the highway.

BIKERUMOR: Between Boulder and daVinci, you actually left the bike industry for awhile.

JAMES: I did.

BIKERUMOR: Why did you leave?

JAMES: In the beginning at Boulder Bikes I learned such a specific skillset and it didn’t seem relevant to me. I can build bikes, but where do I have to go to do this? There weren’t a ton of companies. There wasn’t a ton of opportunity. I wanted to feel like I could support myself in a real way, and so I got into precision welding and fabrication then. That’s where I learned some of the high tech stuff, doing robotics and the cryogenics and the medical and helicopter stuff. That was all fine tolerance work.

BIKERUMOR: And the alloys, man!

JAMES: Yeah, how to work with all sorts of stainless. I did more Ti exploration. It was just a really cool learning curve to find out how to actually weld something so it would pull towards tolerance rather than away from. We would make these compressor mounts for helicopters and they were supposed to come out flat. You’d weld it, you’d weld ears on here, you’d pull it off and it would look like a potato chip. You’d put it in a press and squish it to try to get it back to square. And then we learned that if we preload this plate by putting it in the fixture and bowing it before we put those ears on, it goes straight rather than having to do massive post weld alignment.

The same thing carries over on bikes, welding in chainstays and seat stay bridges. You put them in and weld them, your dropout face is going to turn in. But if you open up the spacing four to five millimeters before you do that, things are pulling in towards tolerance.

BIKERUMOR: And you’re not trying to align it after the fact.

JAMES: Cold setting is- you can only get so much before you start… it only makes sense that you would try to do it on the front end rather than fix it on the back end.

BIKERUMOR: I kind of think there should be a Rumspringa for frame builders, where they have to leave the industry for five years and then come back. It obviously worked out for you. You came back and gained a reputation as this ultimate contract builder. You worked for a lot of people.

JAMES: Yeah. I did. It teaches you how to really be on your game, and it teaches you how to do a little bit of everything which I think is really important.

BIKERUMOR: Were you going into facilities and working in those facilities as a contract builder?

JAMES: With daVinci, I built their tandems in their factory. I welded DEAN titanium for six or seven years, and that I welded in my shop. They would tack them in their shop and would bring me these frames. I would purge them and weld them. And meet them and hand off ten welded frames and pick up ten more to weld. My son, who is 17 now, on the lathe, he was just a babe. I was out there in the garage welding in the garage with the baby monitor. I remember when I could hold him in the palm of my hand. You do what you have to do.

In order for us to just keep the wheels moving, I took on a lot of contract work. I was busier and busier with- I could cherry pick projects I did well on and slowly weld other projects out.

BIKERUMOR: Vote them off the island.

JAMES: Exactly. I wanted to do my own thing. And there was a point where I was finally able to do that.

BIKERUMOR: You got of out of your biomedical crazy alloy fabrication program. Did you go to school? How did you end up in a facility like that?

JAMES: I got a college degree here in town, at CSU, in construction. When I started at Boulder, they were looking for someone with an industrial technology background to streamline the process from ordering material to get bikes out the door. I was hired under that guise. Initially, I was in shipping and receiving, then went back to assembly, and then went over to machining.

But when I went back to welding I had this “oh shit” moment. This is the coolest thing ever! I started taking everything apart- everything. My alarm clock. Any kind of piece of equipment and tried to put it back together. I figured, now the reason why I do what I do is what they talked so much in college about – it takes a lot to sit there and look at a pile of pieces and tubes and try to envision what you can create with them. That’s probably the most satisfying thing about what I do.

BIKERUMOR: You start Black Sheep in your garage, you’re doing contract work. I’m not familiar with early Black Sheep. Were you always curvy?

JAMES: No!

BIKERUMOR: How did your curvy, cruiser aesthetic come about?

JAMES: I had a friend named John Hubbard who approached me in… must have been almost ‘99 or 2000 about building a copy of a Iver Johnson, a vintage cruiser from the 20’s or 30’s. I said, okay let’s do it. We bought some cromoly. We built it up. 29er wheels- it was the first 29er that I really built. Built this thing that kind of looked like that 36er. It was a scorcher. Single bend top tube. This one had straight seat tube, straight chainstay. It was one of the first cruiser style bikes that I built.

I thought, oh, you know, this would be a fun bike to ride on the bike path. Now, all of a sudden, I find myself riding it on trails and ditching my full suspension bike and having this moment of wow, there’s really something cool about this. Then I built the first Ti one and realized that the curves actually do something. They give you some compliance and they create the opportunity for something to bend without extra complexity or parts. That was the part that really got me kind of hooked on curves. Then I go from a bike with a point bend to a gradual curve and, oh, that looks so much better.

BIKERUMOR: What was your goal here, your initial goal for your brand?

JAMES: You know, light weight steel bikes. Steel is real. This is a bike that I built, oh gosh, must have been late ‘99 or early 2000, and I used a Columbus tubeset. What I like about it is it’s simple, and yet there was an elegance to it. It kind of played on older looking bikes but using contemporary materials to build it in steel. People at that time were like, “Steel is heavy. Steel is dead.”

BIKERUMOR: It was so “dead” for awhile!

JAMES: Yeah. Until Reynolds came out with 853 which really set the industry on its ear. It’s a single speed road bike with Campy stuff. It’s got chainstays that are really tall and taper really quick at the back end. That’s the first thing I did after I got out of that build- my own full suspension bike from scratch. What I realized is when you build from scratch, geez, I could spend an hour and a half grinding a cable stop or I can buy one for 50 cents. How much of this do I want to do?

There is an orange bike out there where I made every single thing on the frame.

BIKERUMOR: Sheet metal, huh?

JAMES: Yeah, right?

BIKERUMOR: That’s so rad! Was that for personal amusement or a customer?

JAMES: Personal amusement. That was before I started Black Sheep. It was while I was doing the precision welding and fabrication. I didn’t have an in in the bike industry anymore and I didn’t really know if I wanted something anyone else was building. It was an exercise in “can I do this?” So I just started playing around with that. Get this on paper. It was cool to play around with this. Where do I put the pivot? Where do I put the front derailleur if I put the pivot there? All that was really stressful too, because part of when you build something is that you just want to get it right, and I think I let go of that at some point.

I always figured that at some point is that I would build the perfect bike. What I realized is when you’re going to build another bike, you’re never going to build the perfect bike because one, you’ll get so hung up you’ll never build the thing and two, once you build it, something’s going to change and you’re going to want to do something different.

The first cruiser style bike I built in steel was in ‘99 or 2000. It was probably ‘03 before I started doing curvy stuff in Ti. Again, I was getting a ton of welding experience, and I was figuring out how to really weld Titanium. And then it hit me- the bikes that I started building in steel first were copies of cruisers that I rode in college, that handled similarly.

BIKERUMOR: I mean, if you’re doing curvy tubes, you don’t really don’t think of doing that in other materials. Curvy bikes are steel.

JAMES: Yeah. And then when I learned how to build in Ti, now I could make something with contemporary geometry and build something that gives me a ride that I like. That was 2002, 2003. I’ve been doing that now for 12 years. The cruiser style, what I’m still riding now, I built for a guy for Nantucket Island, that was the first bike I curved. I picked it up and was like, “Hey, there’s really something to this material.” Something that looks like a Klunker but is light and fast like a contemporary bike.

BIKERUMOR: You’ve had a bunch of people coming through the shop in a bunch of capacities, which is something else that I think is exciting. There aren’t a lot of workshop places that you can go through anymore, or where you can work with more experienced builders. I was impressed to see Aaron Barcheck at Mosiac doing it also.

JAMES: He was there while I was building for DEAN, cutting and welding and mitering as well. I saw him go from the guy who was really green to good enough to weld their final product. Then he started his own company and he’s doing quite well. I’ve had a handful of people in the industry that I’ve asked about building really early on be super closed about the process, and a handful be really open.

Chris Sulfrain of REEB, he was a metal smith that got credit for interning with me for an intern with me. At first, I thought “I’m training my competition to be my competition.” Maybe that’s true, but I can’t produce everything I can sell anyway. Really, what I’m doing is helping to keep this trade and craft alive in this country. The more people that I can get inspired to do it, the better. I still do mentoring programs with high schools.

BIKERUMOR: You have kids come through here. Burnsey is here.

JAMES: And Corbin Brady, a friend of Burnsey’s.

BIKERUMOR: Mitering tubes for you?

JAMES: Mitering tubes. Lots of stuff. I get to do the stuff I want- the really intricate stuff. You know, Corbin has gotten so good at things that I can turn him loose, so rather than being out there holding his hand, I’ll say, “We’re doing a truss fork to go on an Erikson,” and turn him loose.

It’s nice to be small and a one person deal, but sometimes you can’t get done everything you want to do.

BIKERUMOR: You’re going to keep on taking on people?

JAMES: I will. It’s very rewarding to see people step in here without much skill, start them on the smallest of operations on a lathe, and see them progress over the years.

BIKERUMOR: And then they are down the street with their own shops.

JAMES: Yeah.

BIKERUMOR: You started with a road bike, but you don’t do a lot of road product now.

JAMES: No. The market really found me for 29 single speed. Now I’m probably 10 to 20 percent road, 10 to 20 percent gravel. The rest is a mix of mostly trail, fat bikes. I got the reputation as the guys who builds curvy single speeds and I’ll take it. It is a market that I can’t saturate. It’s the way that I ride. I started riding 29 single speed ten years ago. It’s the bike that I would ride around on the trail. Then I started riding like that on technical trails. I think I put my energy into bikes that I want to ride. I have no problem with road bikes and road bikers, I just don’t like being on the road with traffic. I figured if I’m riding on trail and I wreck out on a trail, it’s my fault.

BIKERUMOR: Or a bear’s fault. And then you’re attacked by a freaking bear and not an SUV, you know?

JAMES: Right. It’s probably much less likely for that bear attack than SUV attack.

BIKERUMOR: You’re comfortable with your product blend now?

JAMES: I am. And you have to be flexible. One thing I’ve learned is that you have to go with the flow.

BIKERUMOR: So 36ers, huh?

JAMES: Yeah. The first year one we built was maybe six years ago?

BIKERUMOR: An early adopter for that too, right?

JAMES: Yeah, it was mostly to satisfy my curiosity on how to make these things handle. 29ers were going more offset on the fork. How do you do that with a big wheel? Someone approached me about building a 36er. It was the perfect opportunity to make it steer right. So we built it and it was a hoot. Some of these early bikes 36ers that Coaker built in the 80’s actually wore the front tires faster than the rear tires. They didn’t have brakes, it was because the contact patch would get dragged across the ground. So I knew that wasn’t the right number. In playing around with these forks, we have 108mm offset fork, whereas the first one was 105mm.

BIKERUMOR: So that fork is perfect for this type of bike- to have that extreme offset.

JAMES: To handle all the extra mass in the wheel and that offset- you could see the front end deflect away from you initially on the early one. And we built it with a unicrown fork. Okay, we’re going to add a bolt on truss. And then we started making the two piece with the push through steerer to get the added rigidity it really needed. From bike two on, it’s had a truss fork. We’re playing around with these shapes to fit smaller and smaller people.

BIKERUMOR: Are you still excited about the stuff you’re doing today? What’s exciting to you?

JAMES: You know, I built my last personal bike in 2012. I built that one back there a matter of weeks ago. I thought, here I am. I’ve got a clean slate. I can build anything I want. An ultimately, I built something very similar to the bike I built myself in 2012. Still a fat bike. Still a single speed. But something’s changed. That passive front suspension is huge for me.

BIKERUMOR: It looks awesome.

JAMES: It rides well from the little bit that I’ve ridden it and it did what I wanted it to. That’s the thing about doing what I do and that’s what excites me. I get to dream this crazy stuff up, and then I get to make it an see if it works. If it doesn’t, I redesign it. If it does, then I build more. I love that I can work this stuff out in my head and see it come to fruition.

* * *

Bonus NAHBS 2017 Preview

For Salt Lake City, James will be showing off the latest refinements of his passive suspension Deathsplosion forks, including this one developed for his personal 29+ klunker, dubbed “Klunksplosion.” As shown in steel, the fork is 875 grams and has no “tuck” under hard braking. It can be built in steel or Ti, in tapered or straight 1-1/8″ steerer.

The passive suspension is designed to facilitate damping in high frequency scenarios and to not “tuck” under hard braking.

For more information about the North American Handmade Bike Show, check out HandmadeBicycleShow.com