If you’ve ever wondered how bicycle tires are made, our three-part visit to Vee Tire Co. in Thailand will show you how, quite literally, the treads we choose go from Tree to Tire. And it all starts on a rubber farm. Several rubber farms, actually.

Vee Tire is one of the few tire manufacturers that owns its own rubber tree farms. It’s located southeast of their Bangkok headquarters, a bit further than the farm we visited on our trip. This farm pictured here is in Chonburi and is another source of natural rubber latex for Vee, and it’s where their own latex sap comes for processing.

In this part, we’ll show you how it goes from sap to the raw rubber bricks that end up blended with silica, carbon and other materials to create everything from road to gravel to mountain bike tires and more…

It’s a family business

To put the trajectory of Vee Tire Co. into perspective, let’s step back in time a bit. The company is currently run by Bike Sukanjanapong and his father, Vitorn. But the seed was planted by Bike’s grandfather, who came from China, started the rubber tree farm and began his career as a rubber trader.

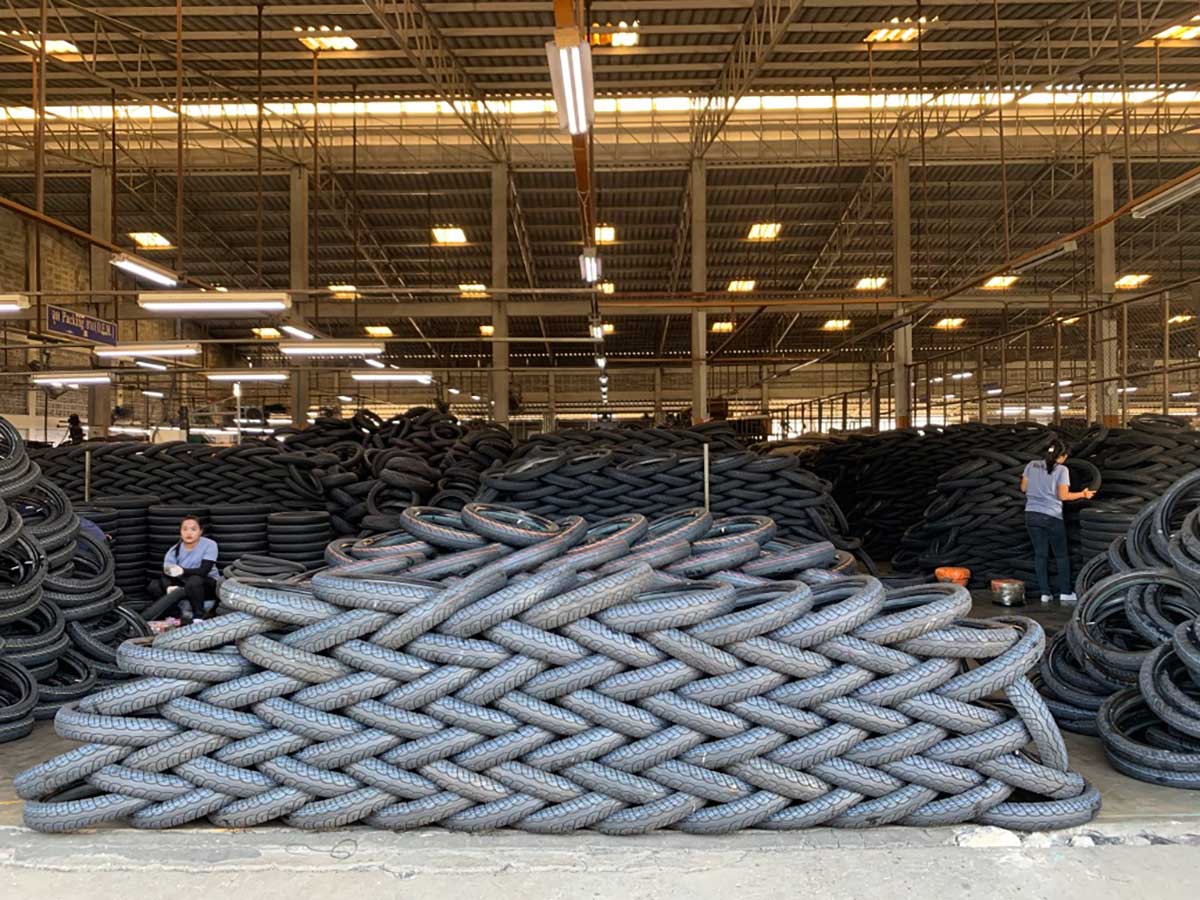

In 1977, Bike’s father launched Vee Rubber, starting with motorcycle and bicycle tires. They were the first rubber company to export bicycle tires to Europe, largely out of necessity – the Thai mafia controlled who could sell bike tires inside the country.

Over the years, their focus has shifted from those to modified racing scooters to go-karts, wherever the volume and interest was. They even dabble in automotive, which they say is a brutal market going up against Chinese brands who sell at ruthlessly aggressive low prices. That’s partly because those designs don’t change often, so their manufacturing is mostly automated.

But bicycle has remained in their line. Since it’s a constantly evolving market (because standards, wants, and needs keep changing) and because the good tires are handmade and labor-intensive to produce, Vee can be competitive.

Besides owning their own rubber source, they also own their own machine shop to cut the molds. This gives them a massive advantage in prototyping and development speed, but now we’re getting ahead of ourselves. First, they have to get the rubber.

How to get latex sap from a rubber tree

On the farm, workers cut the trees first thing in the morning, while it’s still cool and humid so the sap will flow easier. It’s worth noting that “cool” in Thailand means mid- to high 80’s ºF, which is a pleasant winter day there.

Each person cuts anywhere from 800 to 1,500 trees per day, between the hours of midnight and 5am. That’s not a typo. They are insanely quick at slicing the trees.

They use a cutting tool that looks a little like a crowbar, but with a razor sharp, L-shaped blade at the end of the hook. It slices the bark away quite easily.

It only took a couple tries for me to get a clean line and start milking the trees!

Each patch of lines will be worked for five years, then they’ll start cutting on another side of that tree. Trees can start producing sap at 6-7 years old, and they’ll live for about 25 years.

Sap runs from the tree, and it’s a milky white mix of latex and water. Like a cut on your skin, it pools in drops until there’s enough mass for it to roll down the cut line to a small tap that’s been hammered into the tree. This forces the flow away from the tree, where it drips into a bucket:

The tree will bleed sap for about four hours, which is enough to fill a 1500cc cup, and they’ll cut another strip 48 hours later.

The time between cuts gives the sap in the bucket time to dry into a small cantaloupe-sized ball of pure latex, which is then thrown into a truck for transport on a very, very bumpy dirt road back to the processing plant.

Once emptied, the dried layer of sap lining the bucket is pulled out and the bucket is rehung from the tree to capture more.

Turning the sap into rubber bricks

The latex balls arrive by dump truck and are dumped into piles. Workers poke through them to remove any rocks, leaves and sticks, then the balls are left outside outside to dry for up to two weeks.

It starts out pure white and gets darker as it dries. Yes, they’re as bouncy as you’d expect. We have video of this entire process that we’ll share in Part 3 of this series.

Once dried, it’s washed and checked again…

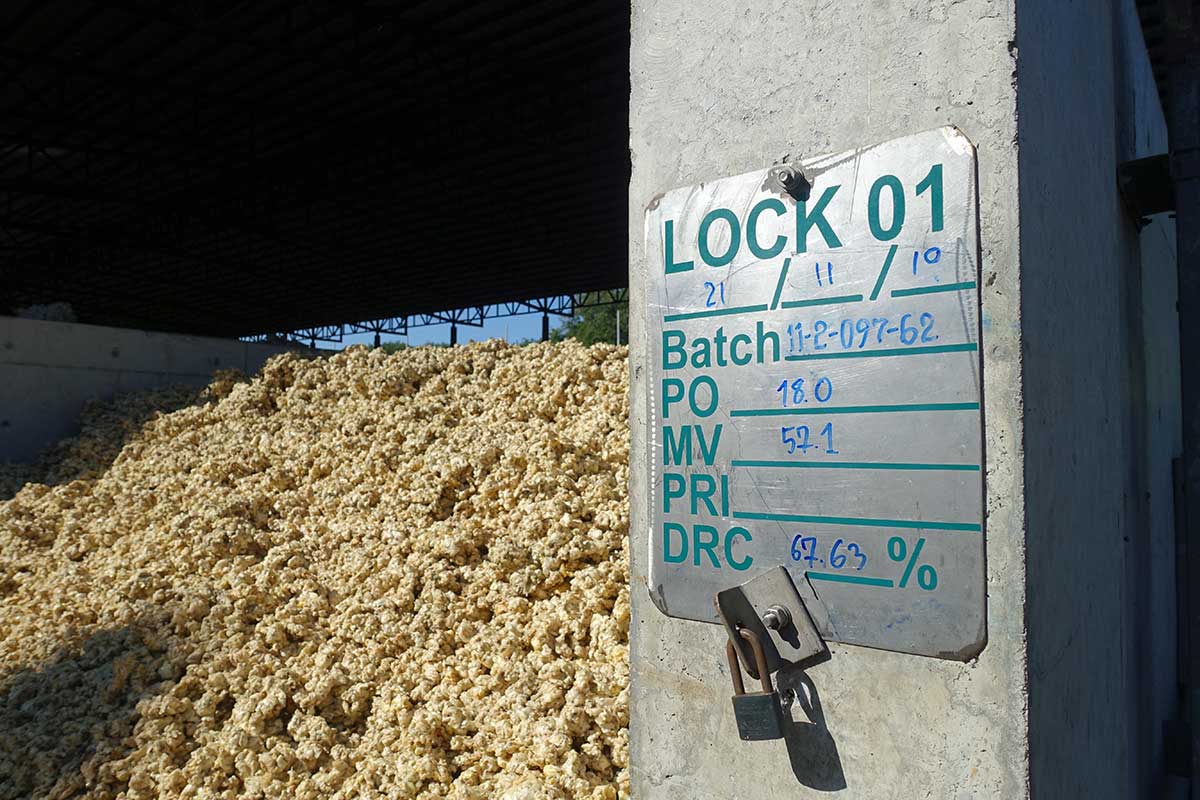

…then graded and sorted. Moisture volume and Dry Rubber Content are the key numbers that indicate quality.

Those batches are then chopped into crumb…

…and pressed into blocks.

Each block is 18-19kg, and by this point they’re basically 100% rubber. They let it sit in the sun for a couple days to dry into a semi-solid block, with a little help by heating and compressing it. The less water in it, the higher quality the rubber.

Then they’re cut into uniform shapes and packed for transport to the manufacturing customer.

Fun fact: This plant captures methane from the waste water from cleaning the rubber, which powers a large part of their facility.

Once packed, it’s loaded into trucks and delivered to Vee Tire Co.’s factory on the eastern edge of Bangkok, where it gets blended into something much more fun. Stay tuned for Part 2, where we show you how it goes from a latex brick into the grippy black rubber that helps us shred the trails!

Disclosure: Vee Tire Co. covered our travel and lodging expenses for this trip, and generally showed us a good time while in Thailand, including a trip to the International Chiang Mai Enduro mountain bike race, which we named one of our top experiences of 2019.