The Rotor INPower is a clever new take on the crank-based power meter that puts all of the electronics inside the axle, which not only protects it, but keeps the rotational mass at the center.

But the location of the electronics is just part of the story. Rotor, which is known mostly for their ovalized chainrings, can show “different” power readings when those chainrings are used on standard spider-based power meters. This happens because the ovalized shape changes the zones of rotational speed at which you’re able to turn the pedals over by making it easier in your dead spots and harder in your power zones. The result, from our own experience, is that the overall pedal stroke is much smoother and the rotational speed seems more consistent to our legs, but they say a spider-based strain gauge may not see it that way.

The design also lets them use the same power meter across their entire range of cranks regardless of the arms, making it perfect for road, triathlon, cyclocross and mountain bikes…

The electronics suite used to measure power output adds only about 60g over the standard Rex cranks, and the arms are the same as their regular cranks.

It uses two opposed strain gauges, sitting in the center spindle positioned 180º of each other. It’s only measuring left side power for now, and here’s why: There are no strain gauges in the arms, it’s all in the spindle, which is measuring torsional flex against the natural resistance to going forward. It can only measure from the left because the force coming from the left crankarm being pedaled has to travel through the spindle to get to the spider. On the driveside, your power is going directly to the spider, which is why so many crank based power meters measure power there. Those measure aggregate power without left or right information. Here, it’s doubling the left side’s number to give you total power.

Angular velocity is measured with an accelerometer. They say most other power meters only measure the speed once or twice per rotation, but speed is never constant. So, INpower measures the exact rotational speed constantly. This last part is particularly important for ovalized rings, which help maintain a more consistent rotational speed compared to a round chainring. This feature also allows it to measure cadence without any additional magnets or sensors.

The cranks stick with Rotor’s UBB (Universal Bottom Bracket) design, which uses a 30mm spindle and their wide range of bottom brackets to let it fit any bike except those with a BB90/92/95 (basically just Trek bikes). The spindle is attached to their left (non-drive) crank arm, so it can be added to any existing Rotor crankset with a 30mm spindle by purchasing just the left side. It’ll also be available as a complete crankset. Like the stealthy looks of it but still not sure about oval rings? They also offer round chainrings.

It knows its position out of the box thanks to factory calibration and the accelerometer. Before your first use, you simply rotate it twice to set it up, and that’s it. It only needs to be done once, but they said even if you just throw it on and go, it’ll still be very accurate.

Because there’s no expansion of a spider or anything due to cold and heat, there’s no temperature compensation necessary either.

It runs off a single AA battery to get approximately 300 hours of use, and will take rechargable batteries, too. Swapping it out is quick and tool free, just twist open the cap.

The only external visual cue that it’s different is the slight extension off the back end of the cranks, which is the antenna to send the ANT+ signal to a cycling computer or your regular computer.

All of the parts are made in Spain. Rotor makes the cranks, spindle, bolts, chainrings and spider all in house. Fellow Spanish company INDRA makes the electronics and installs them in the finished crank arm/spindle assembly.

Their original Rotor Power power meters have the electronics made in Italy and remain in the line. They offer dual sided left/right power measurement, and they’ll still offer the left-side-only version, too…but this new INpower has better electronics and more data points and will eventually just replace the LT. Rotor Power LR also dropped its price to $1,559 in March, down from $2,400. Power LT dropped to $1,079, down from $1,490.

FIRST IMPRESSIONS & USAGE NOTES

While the Rotor Power crankset might still be the top of the line, the INpower brings new metrics to the game, including TE (Torque Effectiveness = positive versus negative torque, which measures how much negative torque your leg is putting on the cranks in the dead zone…if you’re not pulling up on the back of the stroke) and PS (Pedal Smoothness = average power / max power). They say the target for PS is about 35%.

The cranks are sampling at 200Hz (200x per second), which is down a bit from the 500Hz of the top end Rotor Power cranks introduced a couple years ago. That higher res data is available when sending the info directly to INpower software, which is actually read by your computer as 50Hz. A Garmin, in contrast, is only recording at 4Hz.

So far, the Garmin 510, 810 and 1000 will all capture and show the Torque Effectiveness and upload that to Connect and Golden Cheetah, too. They’re working with other cycling computer brands to get that data incorporated into their computers, and it’s already on OSynce, too. They say Lezyne should have it soon, too, for their new GPS cycling computers launched in March but not shipping yet. Pioneer’s computer should read it, too, but won’t display the Torque Effectiveness as it would with that brand’s meter.

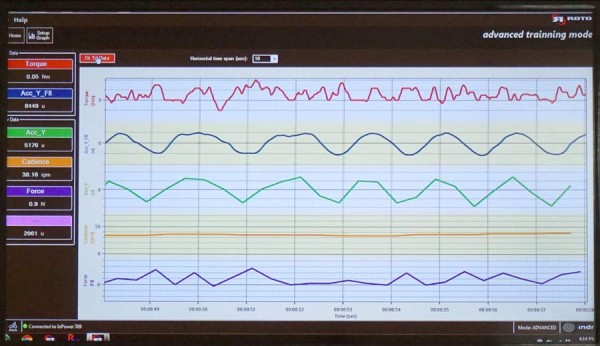

On your laptop or desktop computer, the crankset sends data in real time to their software, which shows the info in either Basic (above) and Advanced modes. Basic shows power, cadence, TE and PS, plus averages for 3, 10 and 30 seconds.

The advanced has more than 30 metrics it’ll show, including battery state. Only about 10 or so are useful for most of us, the rest are really getting into the realm of lab analysis.

The software Torque 360 shows a graph of your complete pedal stroke and lets you see where maximum power is located. Note how the green arrow corresponds to the angle of the crank…it follows along in real time and shows three full rotations worth torque at a time. It also shows your OCA (Optiminum Chainring Angle), letting you clock your oval chainring at the right orientation to maximize your own efficiency. For fans of oval rings, this is a huge help in getting hard data about which chainring position is best in a much easier way than running back to back to back tests at different positions.

There’s an Android smartphone app in development that’ll show the same numbers, just without the graphics of the INpower software. That’s being driven by the MTN Qhubeka pro team, which also sponsored by Samsung, so they can watch the data from the team car on a phone while the athletes simultaneously see it on their cycling computers.

In fact, their team sponsorships are what has driven them to make a mountain bike power meter in the first place. They admit that it’s mostly roadies and triathletes that use power at present, but they made some convincing arguments for using it on mountain bikes, too. We’ll get those those in a second, but given that it’s being driven by professional cyclists’ wants and needs, that means more precise dual leg measurement is in the works, too.

Besides the trails around Santa Cruz being amazing, that’s probably why they chose to introduce it to us out on the trail. After the ride, Rotor-sponsored rider and former champ 24 hour racer Cameron Chambers was on hand to help explain the numbers and some of the benefits of riding with power on a mountain bike. He’s also a coach and founder of Podium Performance out of Colorado Springs.

On the dirt, power gives you a number that shows your real effort so you’re not relying on perceived effort. The difference from a road bike is that there are so many spikes above LT, with trail undulations and obstacles making it very hard to use a 3 or 10 second average to truly see what we’re putting out. Chambers recommends setting one of the screen sections on your cycling computer to Lap Average, which is pretty close to showing something like normalized power.

And Normalized Power is what Chambers says you want to evaluate after the ride. By nature, the power profile of a mountain bike ride is chaotic, spiking and dipping all over the place. So normalized power and above threshold power are more useful measurements. The difference between looking at that and average power is normalized power shows the real toll a ride took on your body and will typically be higher than your average power because it weights the time spent above FTP more heavily.

But that’s just the training aspect.

Power also gives you a firm metric against which to test things like tire pressure, tread patterns, suspension settings and rider position. And the better you can dial those to maximize your own efficiency, the better you’ll be able to perform on the trail.

PRICING & TECH SPECS

While their launch had a mountain bike focus with the Rex cranks, it’s being offered on their 3D, 3D+ and Flow TT road cranks, too. Because everything’s hidden from the wind, they say in testing it can save about 6 seconds on a 40k TT, technically making it the first aero-advantageous crank based power meter.