Exept made their formal debut at Eurobike 2018, showing off an impressive collection of race and endurance road bikes. More impressive, though, was their manufacturing method, which allowed for a truly one-piece, monocoque front triangle with custom geometry. This isn’t easy to do, and it took them two years to finalize the process and find a manufacturing partner that could actually make the frames. As if that weren’t enough of a challenge, they wanted their bikes to be among the very best on the planet, utilizing massive amounts of competitive analysis data to help you use your measurements to get an absolutely perfect fit. Here’s how they do it…

Exept’s Headquarters

Tucked just off the coast of Finale Ligure, Italy, Exept’s offices is in close proximity to amazing coastline riding, steep mountains, and gorgeous scenery. It’s where those ocean-vista images from the Milan-San Remo pro road race are taken, and the area is an outdoor sports mecca throughout the spring and summer.

The team is made up of ex-3T and Rotor vets, with various experiences in automotive composites companies, too. From left to right in the photo above is Alessio (former senior designer and project leader at 3T and Rossocarbon), Alessandro (former engineer at Continental Brakes, owner at Rossocarbon), and Wolfgang (former sales manager at Rotor, product manager at 3T). On the far right is their first hire, Corrado, who is a long time friend of theirs that was part owner of a local bike shop before joining them to assemble and tune the bikes full time and deal with component suppliers.

Step inside and you’ll find their latest builds, likely with one built with the top groups from each of Shimano, SRAM and Campagnolo. Their frames are designed specifically for the type of drivetrain you’ll be running: Mechanical, electronic, or wireless. In the back corner is a fitting room, which they can use for visiting customers but is typically operated by an independent fitter working with his own customers.

The second floor is their open office, with a conference room that doubles as their finance/administrator’s office.

On the third floor is their workshop and store room, where bikes are finished and waiting to be finished. The actual manufacturing is done offsite, which I’ll explain in a moment. Here, they do the design and virtual testing, as well as all sales and marketing. When you create your profile and build your bike with their impressive online configurator, that data comes here and they get to work plotting out the angles and creating the build profile their manufacturing partner uses to set the molds’ shapes.

For wheels, they offer DT Swiss or ENVE. If you opt for the ENVE upgrade, the wheels are built by Pippo Wheels, who handles European wheel building and service for that brand. Or, go for a full Italian build and get Campy wheels and group.

Designing the Bikes

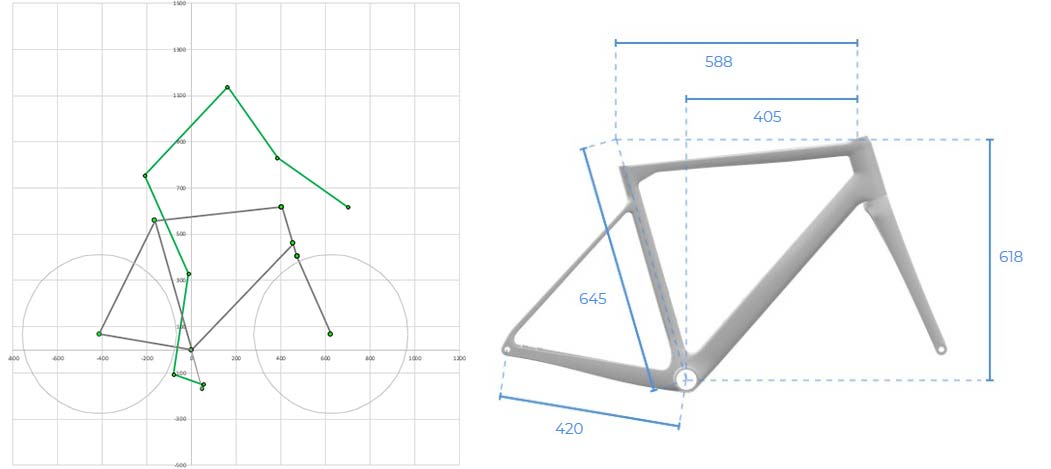

Early on, they started with sketches to create the basic look and feel of the frame. Then the bikes went into CAD design to create parameters like tire clearance, component fit, seatpost standards, etc. It also gave them the overall design aesthetic, which needed to stay the same across all frame sizes. CAD allowed them to see, in real time, how the frame would look as they change the measurements. It’s called Parametric CAD Modeling, and the benefit isn’t just for proving the looks. It lets them check tire and component clearance. This let them set the minimum and maximum parameters that are now used for their production bikes.

From there, it went through 3D rendering so they could see what it would actually look like without all of CAD’s wire frameworks. Then it went to 3D printed models so they could mount all of the components and double (triple!) check that everything fits like it should. Their first design skipped that 3D printing step and they ended up with a pre-production part that didn’t come out as expected, so now everything goes through the full process.

The first design was their “classic” model, but they wanted to push the boundaries a bit and came up with their integrated design. They can do this because of their modular production method. Their molds are made up of pieces, with separate pieces for each of the main junctions. Because of that, they realized that they could also swap in different designs in any of those mold parts, and so the option of classic and integrated designs came to be.

This also means you could mix and match, getting an integrated cockpit on the front end, but with a standard seatpost.

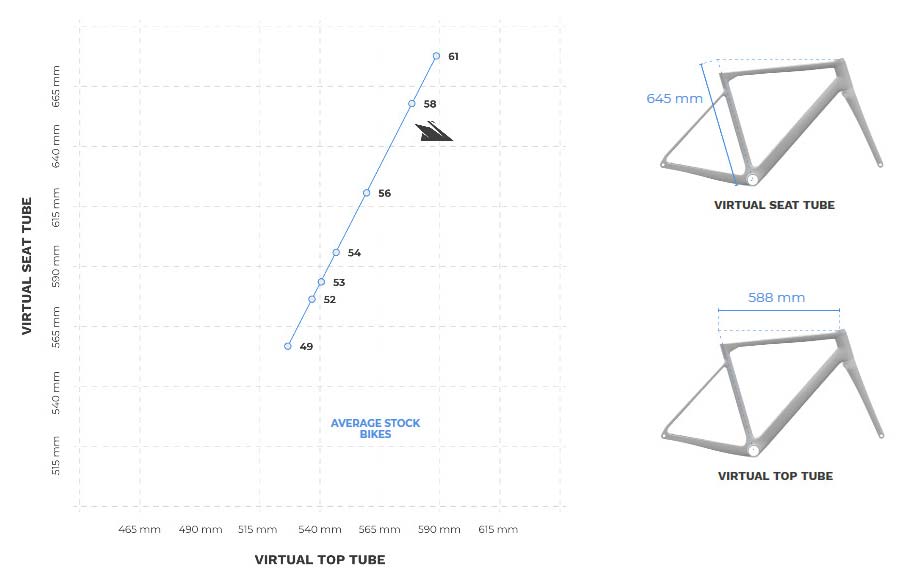

That’s the design. Then came the ride quality, performance and safety parameters. To define the ride quality, they analyzed 18 dimensions across 27 different models of bikes, including both race and endurance designs and men’s and women’s models. These basic geometry numbers showed them the means and averages of what some of the most popular models were using, with particular attention paid to the relationship between reach, wheelbase and trail because that’s what would dictate the overall handling and ride feel.

For stiffness and weight, they looked at Zedler stiffness and weight characteristics for 803 high end carbon frames produced between 2008 and 2017. Those tests measure BB/HT stiffness, Comfort, Weight and Stiffness-to-Weight. All of that was charted, then their targets were set to be in the top 25% of all five categories. That gave them actual numbers to design around. Why only shoot for the 25th percentile? Because the highest numbers aren’t necessarily the best. If the bike is too stiff, it won’t feel good overall. A too-stiff head tube won’t handle well on fast descents.

Safety testing was more straightforward in that there are certain ISO testing standards they needed to pass. Most custom geometry bikes do not undergo ISO testing because, well, each one is unique and made for a specific customer.

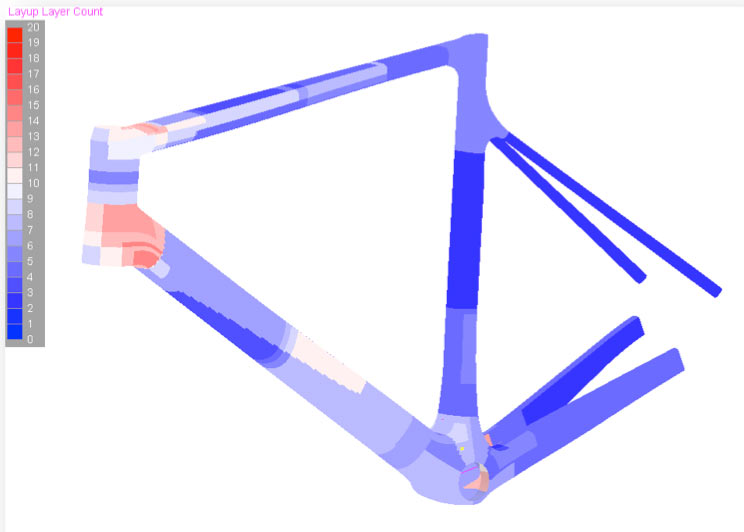

All that info was put into the CAD model, then that was run through FEM (aka FEA) to get the tube cross section shapes in the right place first. Once that was in the right ballpark, they moved on to layup to fine tune it. They define the number, shape, orientation and layering of every piece of carbon…more than 200 pieces per frame. They use a blend of T800 (stronger) and M46J (stiffer, but more brittle) unidirectional fibers. Once all of that is laid up inside the program, they would run stiffness and impact safety testing.

These test cycles were run 87 times before they came to the final layup. The original prototype came in at just 750g but wasn’t nearly stiff enough. The final layup schedule yielded a frame that could come out at 887g, but improved both head tube stiffness and the stiffness-to-weight ratio by 74%. All for only an 18% increase in weight, which was still below their 890g target. The key to all of this, they say, is to know what you’re doing when creating the simulated layups. Without experience, they’d have to make actual physical models and actually physically test them. Which is not only extremely time consuming, but also very expensive.

Then it came time to make actual frames and do testing. Which is where their prior experience paid off…the margin of difference between the simulated results and real world results was just 4% overall. The measured result, if plotted into the Zedler test results, would end up at #10. Out of 803. Not bad for a startup. And a pretty good starting point, but then it gets better. It gets custom.

Making a Custom Carbon Monocoque Bike

The team at Exept wanted to create a full carbon monocoque bike on par with the best in the world. Not the lightest, not the stiffest, but the best performing. While they have all of those numbers to back up such claims, the story they really want to tell is about the process.

The layup is the same across frame sizes, which is what allows them to optimize production efficiencies and offer custom geometry. They stop short of full custom tube layups for different size riders, but they do offer a base layup for most riders and a heavy duty layup for really big riders. This puts them in a middle ground between mass produced bike and something from a private custom builder that might vary the layup based on rider weight and personal preferences, but who doesn’t have to worry about passing ISO testing. Which is not a knock against any of the amazing handmade bike builders we know, just stated to illustrate the difference in requirements when you’re looking to make something at scale.

This is why Exept uses this method: Their frames are designed to perform at the levels they wanted, all the time, every time. Which means they can provide a specific, repeatable layup schedule to their manufacturing partner. They know it will be made the same every time, and pass testing every time.

Where the customization comes in is with the geometry. Their team takes your measurements and plots them against that database of frames and desired handling characteristics, then creates an ideal geometry for you. From there, those numbers are sent to the manufacturing plant in Veneto, Italy, which is not a typical bike manufacturer. They make aerospace parts and armed military drones. And parts for Lamborghinis and F1 teams. Which means they have some seriously advanced equipment. Where small carbon bicycle builders typically have a standard heat press, Exept has access to an Autoclave.

An Autoclave is a larger oven that fits the entire molds and vacuum system inside it. They say it’s the aerospace standard, and that it has far greater control over temperature and pressure than the typical small heat press.

Top-, seat- and down tubes are all preshaped and “soft cured” (my words, not theirs) to hold their dimensions. For now, all of the tubes are made to the maximum length, then cut to size for whatever frame they’re going to be making.

Junctions are laid up directly into the molds, then the tubes are cut to length and placed into the jig with the junctions.

It’s kind of like co-molding, but really more of a monocoque design. It’s not really being over wrapped like in a tube-to-tube construction, because the sheets of carbon that make up the junctions are laid into the interior of the tube and the exterior as it’s all fitted together. Because the tubes are only partially cured, their resin is still soft so that when it’s all put into the oven, everything melts and blends together to create a true one-piece structure. No bonding or gluing, just a one-piece front triangle.

To finish the bike, they make three different size rear triangles. Because they have a predefined chainstay length for both the “race” and “endurance” bikes, this lets them have different sizes to fit onto the full custom front and create a bike that ends up having geometry based solely on your measurements.

Getting to the Right Numbers

Let’s back up a bit. Before they can mold your custom bike, they have to get your numbers. These can come from a professional bike fit, or you can have a friend measure you using Exept’s video guide to ensure you capture what you need. You plug those numbers into their online configurator, choose whether you want Race or Endurance geometry, and add any notes that may help them get to know you. You can also pick the parts you want and see your bike being built up in real time. And watch the price go up in real time. Base price for the frameset starts at €4,500 for the Classic, and €5,500 for the Integrated model (you can see all the differences between the two here and here).

For my fit, they measured me while I visited their Eurobike booth this summer and gave me the numbers to plug into the configurator once home. I also mentioned to them that I really liked the ride of the Cannondale Synapse, that it had become my go-to road bike on most days, so I was curious how their algorithm would interpret my numbers. Would it be similar?

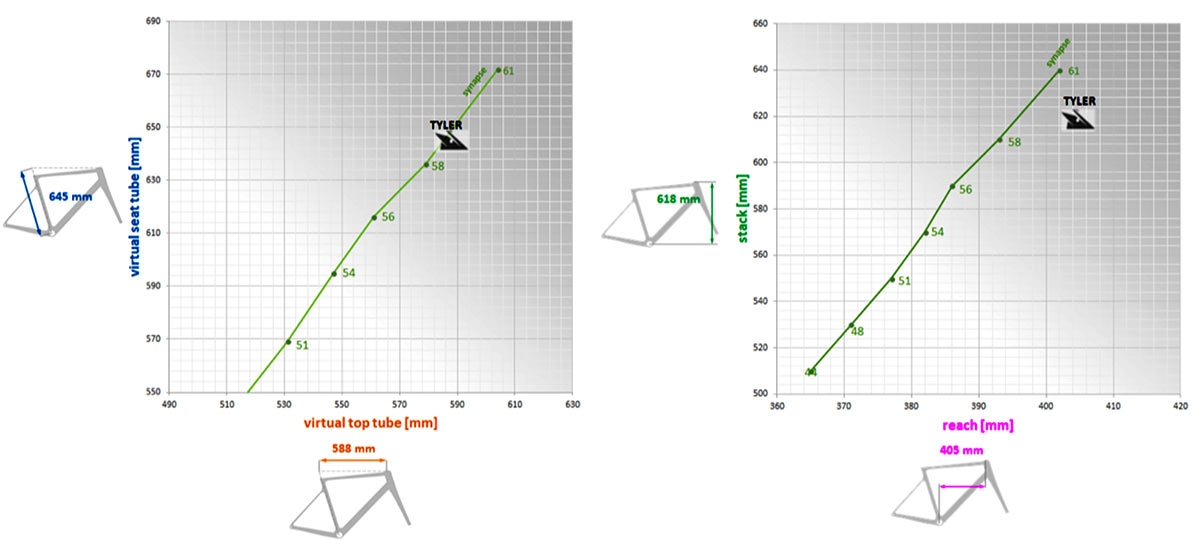

Exept plotted the 2018 Cannondale Synapse’s geometry and stack/reach onto a graph for me, then showed where my measurements would put me. Based on seat tube and top tube measurements, I’d be somewhere around a 59, which Cannondale doesn’t offer. For Stack and Reach, which are arguably the most important measurements for fit, I’m nowhere near matching theirs. And I consider myself to have fairly normal proportions, with perhaps ever-so-slightly longer legs than torso, but certainly not weird. But, assuming you trust their algorithm (and I’d say you should), these graphs show why custom bikes are worth considering.

Each bike’s Stack, Reach, Model Type and actual frame weight are handpainted onto the frame.

You also get to pick which color you want the accents to be, which can go on this matte black base, or a semi-gloss white or glossy Nardo gray.

I opted for the ENVE cockpit, which doesn’t allow for integrated wiring to run through the stem and steerer, so the Di2 junction cover is here, but currently unused. Someday…

OK, back to the geometry. To test how their calculations translated, we rolled out of their office, along the Finale coast, and directly into the hills. Curved switchbacks, rolling connectors, and a fiercely windy descent gave me a good first impression and suggested they’d nailed it. But it was back at home on familiar roads (and without 20mph sideways gusts) that I could tell they’d cracked the code.

The bike felt like an old friend from my very first pedal. Is it the same as the Synapse? No. Exept’s system puts their own personality into the bike, and it shows. It handles differently, but rides supremely. But it’s also still very early in my testing, so I’ll save my long-form opinions for a full review in a few months. In the meantime, they’re worth looking into. Not only does their method and product seem great, they’re also a really great bunch of guys who are passionate about what they’re doing.