In 2010, Pivot came out with the 100mm travel Mach 429, their first full suspension 29er mountain bike. Then, in 2014, they upgraded the carbon layup to create a lighter, stiffer version called the Mach 429 SL. In between, the alloy Mach 4 came out as a 26” mountain bike, eventually morphing into a swoopy, carbon-framed 27.5” XC bike. Now, they’ve combined those models into an all-new, lighter, stiffer and much faster 29er World Cup race bike called the Mach 4 SL.

With the prior model, they wanted to make it lighter, but were limited in how much weight they could take out because the tube shapes needed a certain amount and type of carbon to be strong enough to pass testing. So, they started from scratch, designed new tube shapes with smaller diameters, shortened the chainstays, stretched the top tube and figured out a better way to use the DW-Link suspension. Those changes helped them chop more than 300g off the prior SL, a feat accomplished while also making it a more capable World Cup race bike.

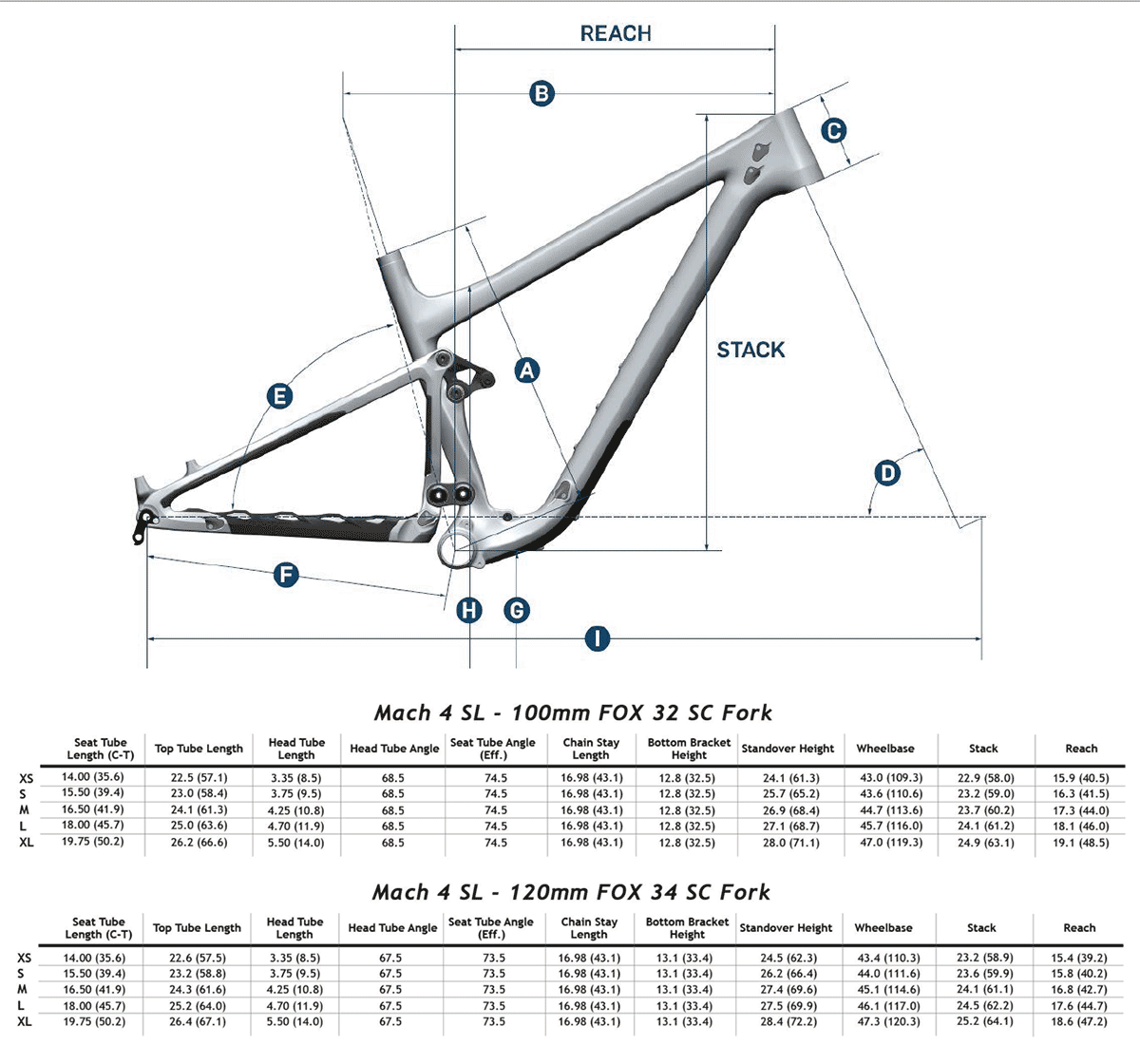

This new Mach 4 SL replaces both the 429SL and Mach 4, and it only comes with 29” wheels. Claimed frame weight is as light as 1,845g (4lb) for an XS frame without shock, and 20.9lb for a complete bike with their top level World Cup Build. It has 100mm rear wheel travel and is designed to work with both 100mm and 120mm forks, but every complete build option except World Cup comes with a 120mm Fox 34 Step Cast fork.

The frame is, in our opinion, one of the best looking Pivots they’ve made yet, with a straight down tube and, actually, pretty much all straight tubes save for the slight curve leading into the bottom bracket shell. This, along with other changes we’ll explain below, means ALL frame sizes fit a large 24oz water bottle, including the XS, and you can get two water bottles inside the XL’s front triangle. Within the size range, they say the bikes will fit riders from 4’10” up to 6’7”.

How did Pivot make the Mach 4 SL so light?

The big things are optimized tube shapes and more hi-mod carbon material, plus a compact front and rear triangle. One of the tricks to using smaller, lighter tubes on the rear end was splitting the upright that connects the front of the chainstays to the seatstays. This created a stronger design that better accommodated the torsion coming from the chain, so they didn’t have to use overbuilt chainstays to compensate for the original single-arm upright.

Moving to a vertical shock placement also allowed for a more compact frame that didn’t require additional material (read: weight) on the top tube to both mount the rear shock and handle its loads. This opened up more opportunities for things like lower standover height, full size water bottle placement, and leaving plenty of room for Fox’s Live Valve. In fact, the standover high on the XS is actually lower than what they could achieve with the old 27.5” wheeled Mach 4 Carbon. Here’s what it looks like with an XL and my 33-34″ inseam:

Then they looked at smaller details like the bearing pockets. On the prior models, they co-molded metal inserts into the frame, then machined those to create bearing sockets and then pressed the bearings in. About two years ago, they started testing Bernard Kerr’s downhill bike with full carbon frames that molded the bearing sockets directly into the carbon fiber. That prototype frame held up for the entire World Cup DH season and the Red Bull Hardline. Pivot was convinced it would work for a production frame. So, the new Mach 4 SL uses almost no metal in the frame, instead pressing the bearings directly into full carbon sockets. Areas that need a thread, like the main linkage pivots, are still co-molded then machined to make the threads.

That means they also went with a full carbon PF92 bottom bracket shell. Founder Chris Cocalis says anytime they can avoid bonding metal parts into place, they can make a better frame. Also, it’s a lot lighter. And, Pivot holds extremely high tolerances for their BB shells, so they say the problems of creaky, poor performing bottom brackets that you might have on other bikes will not be a problem here.

Actually, they hold a higher tolerance standard for their BB’s than they do for headsets, which have long established standards for press-fit performance that no one seems to complain about. And they make their own tooling and measurement tools for the BB shell and send that to their factory, then train their factory on how to use them. Then they reject anything that doesn’t meet their standards. So there’s that. But if you’re still not convinced, you should really listen to our podcast interview with Chris Cocalis…he explains why pressfit bottom brackets are actually the best possible solution.

Modern race-ready geometry

The new, more compact frame sizes allowed for shorter seat tubes, which made room for real dropper seat posts. That seat tube is also steeper, putting the rider’s weight more centered in the bike. The reach stretched out a bit (it’s the same as their longer travel 429 Trail model), and the head tube got slacker, which is where most new bikes are headed. This combination, along with a shorter 44mm fork offset, lets them provide good control and stability on both the climbs and descents.

The chainstays got a bit shorter, too, and they run straight toward the BB, making the actual stay length as short as possible. Not only does this save weight, but it’s much stiffer than a dropped design.

The rear end is standard 148 Boost spacing. Pivot’s been pushing Super Boost on several of their longer travel bikes so that they can increase tire clearance. Here, that wasn’t necessary, and weight savings was a much higher priority. As was Q-factor…their racers like a narrow Q-factor. And a big 38-tooth chainring. This one will still clear a Maxxis Minion DHF 29×2.5 if you really wanted it (and still have 8mm of clearance on either side!), but more importantly it’ll clear the narrowest Shimano Q-factor cranks. So, no “plus” tires, but for XC, it’ll run just about anything you’re actually likely to put on it. Especially the 2.2” tires they ship with.

Let’s talk suspension

The biggest change for this model is the move to a fixed upper rocker. All of their other models are now driving the rear shock off of an upper rocker, whether directly or with a clevis wrapped around the seat tube to reach the shock. Now, the Mach 4 has that, too, which opened up the ability to change the shock’s orientation because it no longer relied on the seatstays to push it. And, perhaps as a little teaser of things to come, none of their recently introduced bikes use a clevis anymore, too…only the Mach 6 and Switchblade still have it. Any guesses on what’s coming next?

For standard suspension models, by which we mean those without Fox Live Valve, the rear shocks get size-specific tunes – M/L/XL frames have a firmer compression setting than the XS and Small, which should suit larger and therefore usually heavier riders better than if they put the same tune across the board.

And they tuned the non-Live rear shocks to have slightly firmer compression damping than those with Live Valve. Why? Because the Live Valve works so much faster and more frequently to maximize the rider’s efficiency, that when it’s Open, it can really be Open because as soon as you don’t need it, it’ll be closed again. Conversely, with a remote that you control, you’re probably going to end up in the Open mode for longer stretches of time, even when you’d be better off in a firmer mode. So, they kept it just a bit firmer to help you out a little.

That’s great, but wasn’t Pivot’s DW-Link suspension already pretty efficient? Why does it need this? I asked Cocalis this very question, to which he responded: “Well, it doesn’t need it, but it allows us to open up the usable range of the bike. With manually operated shocks, you have to choose which end of the range you’re going to go with. With the Live Valve, we can go to the softer side of what an XC bike would normally be and have more of a trail bike feel on the descents, but still be extremely efficient when you need it to be.”

Sounds cool, tell me more about Fox Live Valve

Live Valve will be a $1,900 upgrade, which they say is a better choice if you’re waffling between that or the otherwise very popular carbon wheel upgrade. Why? Because, first of all, the aftermarket price for Live Valve is more than $3,000. Second, they say their racers still like having a lockout, but the Fox system will open and close the system in real time hundreds if not thousands of times during a race. It adds just under a half a pound to the bike, though…so maybe you do want that carbon wheel upgrade, too.

Side note: The reason it costs so much more to add on aftermarket is because you’re buying a new fork and shock, too. The Fox Live stuff isn’t retrofittable to existing forks and shocks. But obviously, Pivot already builds the cost of a fork and shock into the complete bike price, so you’re only paying more for the actual Live Valve stuff.

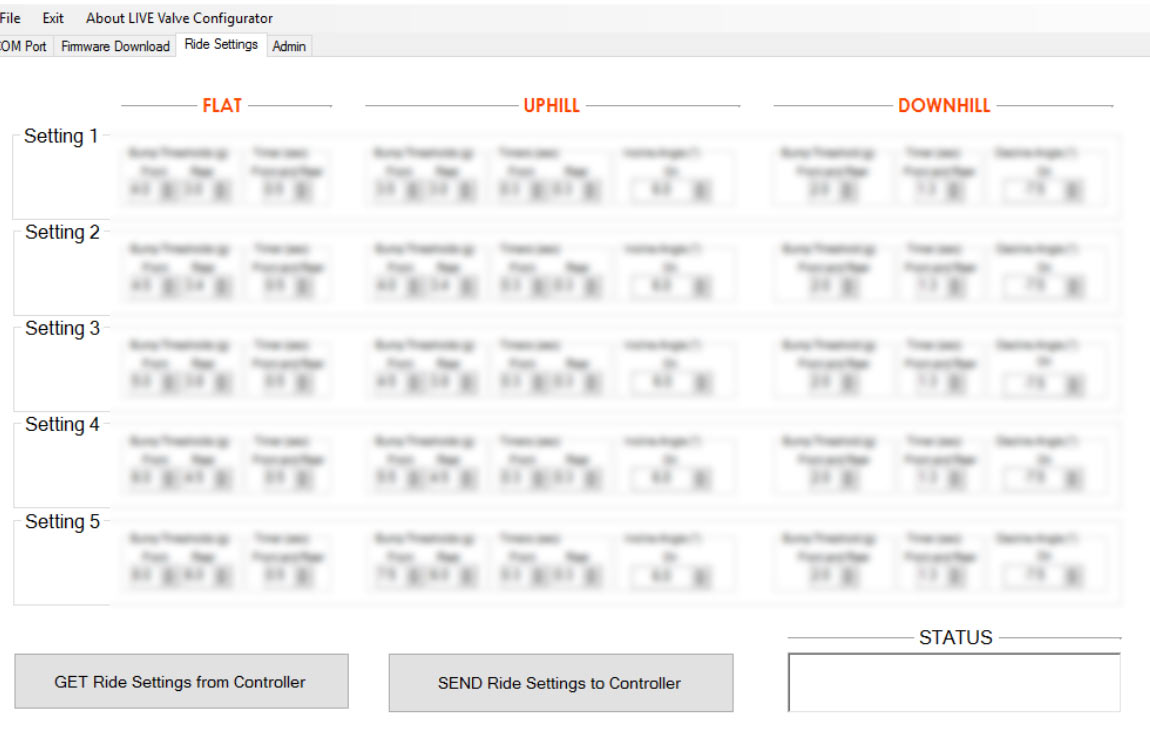

OK, but what is Fox Live? We covered that really well in this post, but the gist of it is this: It’s a pair of sensors that detect movement at 1000 times per second and can open and close the compression damping valve in 3ms, which is faster than you’ll ever notice. About 4x faster, actually. So you won’t notice it working, except you’ll notice how much more efficient you are. The battery will last for a week’s worth of rides, and if it does die on a ride, it’ll simply open up the suspension so you can finish the ride with working suspension. You also still have an external Open Mode compression adjustment (they recommend running full open so the suspension can do what it’s supposed to) and the regular full range external rebound adjustment.

The actual algorithm that controls the fork and shock’s behavior is set by Pivot. Which is why they could make the Open Mode’s valving a little lighter. For the Firm mode, they didn’t go full lockout because they wanted the bike to still sag a proper amount. Fox’s engineer was on hand and explained: If it were a complete lock out, the shock would top out because the rebound circuit would keep popping it up, but the electronic circuit wouldn’t open on smooth terrain, so you’d end up with no sag and then, when it did open, it would feel like a “trap door” with a bigger-than-ideal amount of movement. Basically it would feel weird. So, they left a little bit of bleed in the system, which translates into a really firm but not quite locked out system that’s still able to move with your pedal stroke just slightly.

One more cool thing: They, and maybe eventually you, can update the suspension’s performance via firmware update. In fact, Pivot says they’re constantly evaluating the performance of the system on their World Cup racers, and if they learn something new, they may push that out to everyone.

The Fox Live Valve only controls the low speed compression circuit. The high speed circuit is still tuned in partnership with Fox to get the bike’s performance where Pivot wants it. One more thing: You want to set your air pressure and rebound with the system turned off.

Surprisingly, the new Mach 4 SL is not quite as Di2 compatible as some of their prior bikes. You can still do it, but the battery containment designs from yore are not here, so you’ll have to get a little creative with internal battery placement…or use the old external battery. But it’s just fine with the new SRAM Eagle AXS, as most any frame would be, and they say it will hopefully work well with whatever the next generation

Do I have to run a 120mm fork?

No, the bike was designed to run both that and a 100mm fork. But technically, the geometry was specifically designed around a 120mm fork, and the bike will have a 67.5º head tube angle with a 120mm fork and 68.5º with a 100mm fork. Why put a 120mm on a pure XC race bike? Well, they (and a lot of other brands) started spec’ing their 100m travel XC bikes with 120mm forks years ago because everybody wanted to use them as trail bikes. And they sold quite well like that. Dealers liked it, riders liked, and so Pivot liked it. And it’s fun, and it makes the bike more capable and more appropriate for things like Marathon races, all day epics, etc.

Other geeky details

They spec a custom Enduro Max bottom bracket with Mobile 1 waterproof grease on their bikes. There’s no ISCG mounts for a bash guard or chain guide, but there is a rubberized protective bit on the lower section of the downtube.There’s also a custom rubberized chainstay protector with fins to keep the chain quieter and more controlled when it does hit…and it’ll hit more frequently because they raised the chainstay so much higher than the prior model. Those fins work by interrupting the wave that forms when the chain is allowed to bounce uncontrollably, which still happens even with clutched rear derailleurs. It’ll pair a Race Face dropper lever with the Fox Transfer dropper posts. Different frame sizes get different travel dropper seat posts, which is laid out in the build spec charts.

Why no 27.5” wheels?

Simply put, 29ers are faster. They did build some test mules and put them under Chloe Woodruff, but as much as she liked the playfulness of her 27.5” bikes, she was faster on the 29er prototypes. That’s one reason. The other is product development beyond their bikes. Fork selection, tire selection and other cross-country specific technologies and parts are all slowing down for 27.5” wheels. So, if their racers wanted to keep using the best parts for World Cup racing, they needed to be on a 29er.

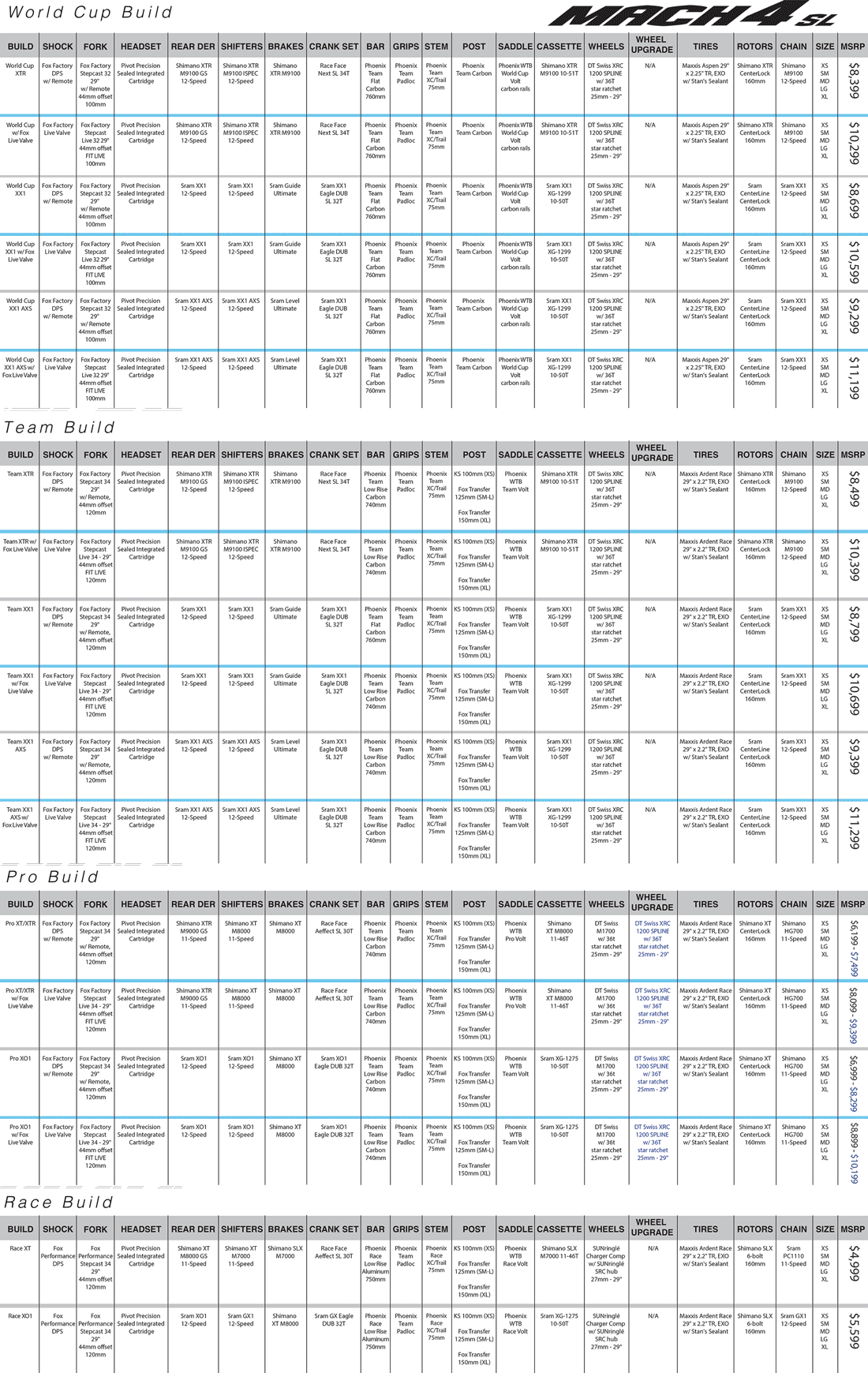

Mach 4 SL actual weights, specs, geometry & pricing

The bikes are light, and achieve their lightest complete bike weight of just 20.9lb (actually, just 20.88lb on our scale, size small) with the World Cup model. Shown top-left in the photo above, it gets a flat bar, standard seatpost, and is the only model to come with the 100mm travel Fox 32 Step Cast fork.

Top-right is a size small Pro XT/XTR build, which gets alloy Race Face Aeffect SL cranks, DT Swiss M1700 alloy wheels, and mechanical-remote suspension lockouts. This one weighed in at 26.15lb. On the bottom-left is the XL size of that same bike, which comes in 26.63lb. So, all else being equal, figure about half a pound gain going from Small to XL frame sizes.

On the bottom-right was my test bike, an XL Team XTR build with Fox Live Valve, DT Swiss carbon wheels, and the Race Face Next SL carbon cranks. Even with a little dust on it and the extra electronics and battery, it came in more than a pound lighter than the Pro XT/XTR model. It’s worth noting that lower end builds get smaller 30- and 32-tooth chainrings, and the racier top end builds use 34-tooth chainrings. Here’s the complete spec chart for all models, with pricing, click to enlarge:

And here’s the geometry chart…

The bikes are already shipping to dealers, so talk to your local bike shop if this is the bike for you. Curious how it rides? Check out our full review, coming soon.