At the start of this year, I was still not entirely convinced that electronic wireless mountain bike groups were something that I really wanted, or needed on my bikes. In my experience, they tend to be heavier, more expensive, less robust, harder to repair, easier to scuttle a ride by forgetting a battery, and seemingly slower to shift – all for the sake of getting rid of cables, which seem to function perfectly fine as long as you do a little maintenance every once in a while.

But with SRAM pumping out the AXS groups, and most recently ‘ending the mountain bike drivetrain‘ with Transmission, the writing was on the wall. Shimano’s hand was seemingly forced to create a wireless competitor, and like the launch of the first XTR 12-speed group, they were already well behind.

Just like that first XTR mechanical 12-speed group, though, the new XTR Di2 group is worth the wait. More importantly, it finally makes a solid argument in favor of the wireless MTB group with more adjustability, increased durability, and features you won’t find on mechanical.

Like most of you, my first impression of the new group came from those leaked photos that surfaced around the same time we dug up the most recent Shimano patents which turned out to reveal a lot about the new group. I’ll admit that I was a bit underwhelmed by the leaked photos, but I tried to keep an open mind as we were invited out to Tucson, AZ to see the new group. In person, the new XTR looks way better than in those poorly lit photos, and once you learn about all the reasons behind each design feature, you gain a much better appreciation for why it looks the way it does.

A Stronger (and Smarter) Rear Derailleur

One of the biggest design features of the new group is increased durability and the ability for the derailleur to essentially keep itself out of harm’s way. As soon as you add electronics to your rear derailleur, a broken unit becomes a much bigger issue. Worse, when that broken derailleur happens out on the trail far from home.

SRAM’s answer was the implementation of the Universal Derailleur Hanger and the Full Mount direct mount standard for their Transmission derailleurs. Full Mount makes the derailleur’s attachment to the frame strong enough so you can stand on it, but that then threatens to make the rest of the derailleur the weak link.

Traditional Hanger For the Win

Shimano took a different approach, which had to be at least partially inspired by avoiding SRAM’s patents. Instead of using a direct mount approach, Shimano is sticking with the traditional derailleur hanger. Why? Because in their eyes, the derailleur body should always be stronger than the hanger. When engineered correctly, a derailleur hanger will absorb the kind of impact where a derailleur lands on top of a rock. The hanger will bend or break, and you can replace it trail-side with minimal damage to the derailleur itself, so you can pedal home.

The introduction of SRAM’s UDH actually helps here, since it’s easier than ever to find the right derailleur hanger to keep as a spare. Shimano does recommend a premium CNC-machined aluminum derailleur hanger like those from Wolf Tooth Components, North Shore Billet, Wheels Manufacturing, etc, which offer the most precise shifting, but any will work.

I can already hear the “but it’s not direct mount,” comments, but I am not sad to see Shimano using a traditional derailleur hanger here. I can appreciate the thought behind the Full Mount, but in my experience, for it to work properly, that interface between the Full Mount and the frame has to be perfect (which in my experience seems to be about a 50% chance). I also won’t miss having to lug around a torque wrench and an 8mm bit when traveling, if you have to remove the derailleur to pack your bike, to make sure that Full Mount bolt gets to 35Nm. Theoretically, you shouldn’t have to touch the Full Mount bolt on a ride, but that hasn’t been my experience either, which means even if your multi-tool has an 8mm Allen wrench fitting, the tool probably won’t offer enough leverage to properly tighten that bolt.

Not all that long ago, derailleur hangers were the Wild West. Everyone had a slightly different model from bike to bike, and it was impossible to track down a replacement quickly. They were also noodly, and made from flimsy metals in an effort to make them bend before equally flimsy rear derailleurs would bend or break. Credit to SRAM for finally pioneering a truly universal derailleur hanger and getting us past those dark times. But now, Shimano is stepping in with a derailleur that is stronger than that UDH hanger, which brings us into derailluer/hanger harmony and adds another layer of protection to keep you rolling on your ride, and it makes the bike easier to set up.

In addition to the derailleur hanger offering protection against derailleur damage, the derailleur itself is designed to get out of the rock’s way. The Shadow ES wedge shape to the body is intended to shrug off impact to the outside of the body, and if you hit something really hard, the automatic impact recovery feature allows the motor to absorb the shock of the impact and move the derailleur inboard. It then moves automatically back into the gear you were riding in.

Tucson Has a Lot of Rocks

This whole concept seems to be the main reason we were invited out to Tucson – in hopes of us smashing the shiny new derailleurs on one of the millions of rocks in the desert. One of the odd things about this concept is that if it works correctly, you probably won’t even know you hit something. The Shimano team excitedly showed off some light scuffs on the prototypes as a result of their test riders purposely crashing into rocks, which was all that was left from encounters that would normally render a derailleur worthless. I think Shimano would have been happy to see some of us recreate those tests in Tucson, but years of training our lizard brains to avoid blunt objects with the expensive dangly bits overpowered our motivation to purposely damage brand new derailleurs.

It is highly likely that we did actually kiss some rocks out there with the Di2 derailleurs, but Shimano purposely used resin materials for the P-Body, battery door, and bottom of the parallelogram cover since the material has the ability to hide repeated impacts, unlike raw aluminum. Those pieces are also replaceable, so if they get too beat up, you can make it look like new. That’s why a good chunk of the derailleur body has that matte-black, plasticy look to it – polished aluminum might look better initially, but give it a few rock strikes, and the resin materials will look better in the long run.

After our time in Tucson, we returned home with the bikes in hopes of giving ourselves plenty of time before the launch for a proper review. I was pretty sure that my impressions were already fully formed, but I jumped at the chance to pedal around a new XTR build without making it too obvious that I was riding an unreleased groupset, particularly a bike like the Ibis Ripmo. I’ve already spent a lot of time on this bike as the Ibis Ripley, but with longer suspension travel and a few different links, the bike transforms into the Ripmo, and it was a perfect choice for Tucson.

This is How an Electronic Group Should Shift

If I had to pick one feature that stood out the most on the new group, it would be a tie between shifting speed, and shifting feel. Simply put, if you’re used to the shift speed of SRAM Transmission, the new XTR group will feel impossibly quick. I had the chance to demonstrate the XTR Di2 group shift speed against SRAM XX Transmission to a friend who had never seen either of them in person, and when he saw how much slower the SRAM group was, he thought I was pulling his leg and deliberately shifting it slowly.

Shimano wouldn’t provide us specific speed info on the shifts, but by stopwatch you can shift up or down the full cassette in under three seconds. The same task on the Transmission group takes about seven seconds. You can shift up and then back down the XTR cassette in the same amount of time it takes to shift one direction on Transmission.

That shift speed absolutely comes into play on the trail when you need to quickly bail yourself out on a tech section, or jump to a much harder gear in a race. More importantly to me, you’re never left waiting for the derailleur to catch up to your shifts. On Transmission, I find times where I need to drop multiple gears and you push the button multiple times, but you’re pushing the button faster than the derailleur moves gears, so you end up getting ahead of it and then forget how many times you’ve pushed the button and often end up over or under shifting.

I’ve not had that experience with wireless Di2. Partially because of the incredibly fast shifting, but also due to the shift options themselves. The ‘wireless shift switch’ is styled after a traditional two-lever Shimano MTB shifter, and the two paddles function similarly. But while a single click nets you one gear, there is also a double-click feature that jumps two gears. Hitting the double click multiple times seems to be the fastest way up or down the cassette, but you can also just hold down either shift lever to let the multi-shift work its way up or down automatically. To make the single or double click easier to use, the single click is a light touch (think mouse click) while the double click is heavier (more like a mechanical shifter).

Multi-Shift can also be tuned in the E-Tube app, allowing you to change the shift speed, what section of the cassette can be used, and you can limit the gears to 2 or 3 at a time (no limit is the default).

With three different ways to shift and blazing speed, you’re always in the right gear without any frustrating delays. There’s also a third shifter button that can be programmed to do different things, including on-the-fly trim adjustment for the rear derailleur. Shimano had a racer that wanted the ability to trim a derailleur out mid-run if they bent the hanger and wanted to adjust it into a certain gear. That’s a pretty specific use case, but it can also be reprogrammed to do things like control your Garmin.

Shifter Ergonomics are the Best

The ergonomics of the Shimano XTR Di2 shifter are another huge win for the Blue team. In testing, Shimano tried a number of button-style electronic shifters, but inevitably, testers wanted to try it with something that felt more like a traditional shifter.

But compared to a mechanical Shimano shifter, the wireless shift switch is far more adjustable with individual shift paddles that can be adjusted in multiple axes, as well as inboard/outboard and rotational shifter adjustment. It almost borders on too many adjustments, but I’m happy to have the ability to position the shift paddles exactly where I want them. You’ll likely need to spend some time playing with the adjustments, but once you’re dialed in, it feels so good.

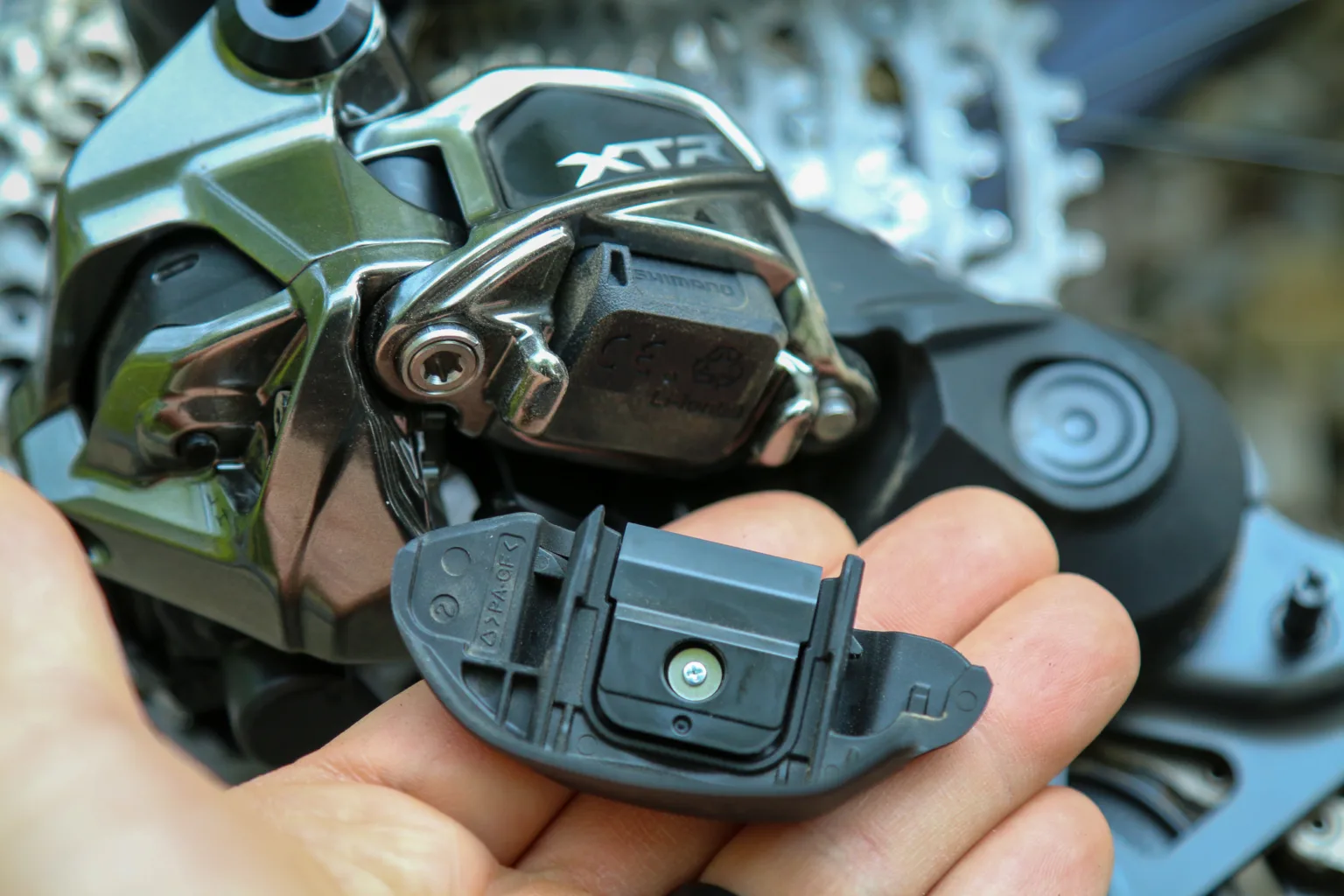

Battery protection & performance

Anyone who’s ever had issues with AXS batteries making good contact with the derailleur will appreciate the battery protection built into the Di2 derailleur. With the battery tucked inside the body, and under a protective door with a breakaway function designed to keep the battery in place, the Di2 derailleur should have very few issues with battery contact. It also places the terminals facing up, and surrounded by a tight seal to keep dirt and water out of the contacts. I would avoid pressure washing the derailleur, but it’s impressive to see how clean the terminals have stayed so far.

Shimano claims you can expect around 210 miles of range, but it all depends on how you’re shifting, and likely weather and riding conditions. If you live in hilly areas where the topography frequently shifts, you may see a bit less than that, but again, it all depends on your riding style.

Battery life can be checked on the derailleur by hitting the program button and checking the status of the LED, or you can open the E-Tube app and get the battery life of both the derailleur and shifter.

Stabilizer performance

I wasn’t sure how to feel about the loss of the clutch. The introduction of the clutch seems like such a pivotal moment in mountain bike derailleur design, it’s hard not to feel like we aren’t going a bit backwards here. But Shimano’s arguments against the clutch seem sound (see our tech story for the explanation), and the dual-spring slim stabilizer seems to be doing the job.

Every so often, I hear a bit of chain slap on a big impact, but otherwise, the drivetrain stays nice and quiet. Any noise from the derailleur seems to stem from large repeated impacts when the bike is at high speed. The chain has never derailed, and I haven’t experienced the chain slapping my ankles as I have in the past with even some clutched derailleurs.

If it really requires no maintenance in the future, and maintains this level of performance, it seems like a worthwhile trade-off.

Metal Cranks Deliver

For ultimate reliability, it seems like you would want metal crank arms rather than carbon. Ironically, it was Shimano’s Hollowtech II aluminum cranks on the road side that used a two-piece bonded design that were part of a massive recall due to delamination of the two halves. Shimano didn’t have that issue on the MTB side, but they also wanted to offer the most reliable cranks they could make. That led to the metallurgical wizards creating an even lighter hollow-forged arm. They’re impressively light for an enduro-rated aluminum crankset, and the all-metal construction should make them a popular choice.

Initially, I felt the bold two-tone graphics seemed a bit NASCAR, but I think it’s growing on me. I think.

Shimano has kept with the 24mm Hollowtech II spindle, so existing bottom brackets should all be compatible with the new cranks.

Brake Performance

Outside of the wireless shifting, Shimano also has a big launch here with the brakes. The levers are completely redesigned with a pull-master cylinder, and a new lever pivot placement and upward angle. The calipers and brake pads have been updated to reduce noise, and the brake fluid has been changed to a Low Viscosity Oil.

It’s a completely new brake, and it feels it on the trail. It still has that characteristic Shimano feel, but it’s more refined. I found myself having to relearn how to brake especially around technical switchbacks since the brakes have so much modulation, and quick but consistent ramp up to impressive stopping power. At first I was braking too early, and finding myself drifting to the inside of the apex too early. Once I learned to trust the power and the feel of the front brake especially (this has always been a struggle for me since the nerve injury in my left arm), I was diving deeper into corners, braking later and harder, and getting on the power sooner.

I don’t know if these have quite the same amount of power as SRAM Mavens, but they’re close – and with better modulation. On my bike, Shimano has definitely fixed the pad rattle issue, so as long as the LV Oil solves any wandering bite point issues, it seems like Shimano is back on top of the brake game as well.

I’ll point out that at first, I wasn’t sure about the new brake lever angle and positioning. But after tilting my levers farther down toward the ground than usual, I found them very comfortable and easy to pull.

Wheels

On top of all that, Shimano has new wheels for both XC and Enduro as well. Our test bikes were all fitted with the M9220 Enduro wheels, which are built with 30mm internal width asymmetric carbon rims, steel j-bend spokes, and the new Low Drag M9210 hubs. This Direct Engagement freehub design offers 3.5º of engagement, which definitely isn’t Hydra 2 level, but it seems plenty fast for most situations.

The hub does seem to roll and coast quite well, with a quiet but distinct buzz. Again the XTR graphics are pretty bold, but they’re positioned in a way that it’s hard to really pick up on the fact that it says XTR on the rim until you’re looking down on top of it.

The wheels aren’t too flashy, but they seem very well built (and easily repaired) with a competitive weight and a decent price tag. If these prove to be as durable and reliable as other Shimano wheels, they should become a popular option.

Riding Away

I have a love/hate relationship with battery-powered things. I love the convenience and power that they provide, but I also hate the countless chargers, cables, and the need to always make sure you have the right battery for the right equipment (and that it’s properly charged).

We had gotten to a point where mechanical MTB drivetrains were really good. Now, it seems like wireless electronic drivetrains are catching up. There have been multiple times recently where I’ve specifically requested review bikes without electronic drivetrains because I didn’t want the drivetrain eccentricities to bog down my opinion of the bike as a whole. That will not be happening with any new Di2-equipped bikes.

Yes, Shimano took their time with the group, but it shows in the final product. XTR Di2 wireless feels like a drivetrain that you want to upgrade to because it’s actually better, not just because it’s the cool new thing.

Don’t get me wrong – I still love a good mechanical group. But I would not hesitate to buy this group for my own bike. Which is a first for me and electronic MTB groups.

Further Reading on Shimano Di2

Complete breakdown of weights and pricing for XT Di2