Suspension isn’t limited to undamped leaf spring forks of the more mechanically complex YBB softail frames like we’ve dug deep into over the past weeks. If you have a full-suspension bike, it needs to move smoothly & freely to get the most out of its rear wheel travel. So how does your bike pivot?

How does the suspension move in your bike frame?

Breaking it down to the basics, if your bike frame has a suspension system to allow the rear wheel to move and absorb impacts, you are going to end up with some moving parts. No matter what material the frame is made of, we generally want to limit rear wheel movement to the vertical plane, while maintaining horizontal stiffness. To do that frames generally rely on one of three methods to allow for rear wheel movement – controlled material flex, pivoting elements with bushings, or pivoting elements with bearings.

So which is which? How can we identify each and what are their benefits?

Engineered Material Flex

The most basic way to allow for wheel movement is to allow the rear end of a frame to flex. That’s what it going on in the titanium chainstays that act like the spring on the Moots YBB softail design. But this isn’t limited to titanium. We are seeing more and more carbon frames that engineer in flex to the rear end, since the material lends itself well to reinforcing a frame against flex on one direction, while allowing it in another through careful material layup.

The complication in building flex into your bike is to allow vertical movement at the rear axle to absorb impacts, but preventing any horizontal movement (side-to-side flex) or twist in the rear end that would both sap precious energy from your pedaling inputs and make the bike difficult to keep in a straight line, especially when riding rough terrain. Carbon hardtails like the Silverback Superspeed (above) with its flattened seatstays that bypass the seattube are a good example of engineered material flex for limited rear wheel movement.

BMC’s carbon softail Teamelite takes it a bit further like the Moots, offering 15mm of elastomer controlled travel via engineered carbon flex in the rear end.

But you don’t need to eliminate all of the pivot points to get the benefits of engineered frame flex. The reason to eliminate pivots and replace them with flex is generally weight reduction and simplicity. With fewer components, the frame can be built lighter. With fewer mechanically rotating parts, the frame will require less maintenance to keep running smoothly.

Single pivot or four-bar suspension designs traditionally relied on a pivot either located on the seatstay or chainstay to allow the frame to cycle through its rear wheel travel. But bikes like the Cannondale Scalpel have long used flex in the seatstays to permit rear axle movement. You still need the main pivot, and often some pivots in a linkage driven shock like the Scalpel. But the solution can still often be lighter and easier to keep running smoothly.

What is a bushing, and why are they in my frame.

A bushing is essentially just a sleeve of a low-friction material that is inserted into a frame at a pivot to allow rotation around the pivot’s axle. If you just had a steel or aluminum axle rotating inside of a steel or aluminum hole there would be a ton of friction, and dirt & regular corrosion would make it even worse. But by adding a slippery, low-wear material like some advanced plastics like Delrin, most of the friction goes away.

So why use bushings at all? Bushings are relatively cheap, have few moving parts, and are lightweight. But they do get a bad rap. There has been a general trend to move away from bushings to replace them with bearings. But in situations where you only have limited rotation – like a short-link suspension bike – and relatively heavy loading, bushings can be hard to beat. The newest Ibis Ripmo specifically has bucked the bearing conversion trend and returned entirely to igus self-lubricating plastic bushings in their lower links. They say it saves 80g, is a more appropriate solution and they stand behind them with free lifetime replacement on the bushings.

Why does my suspension have (sealed cartridge ball) bearings?

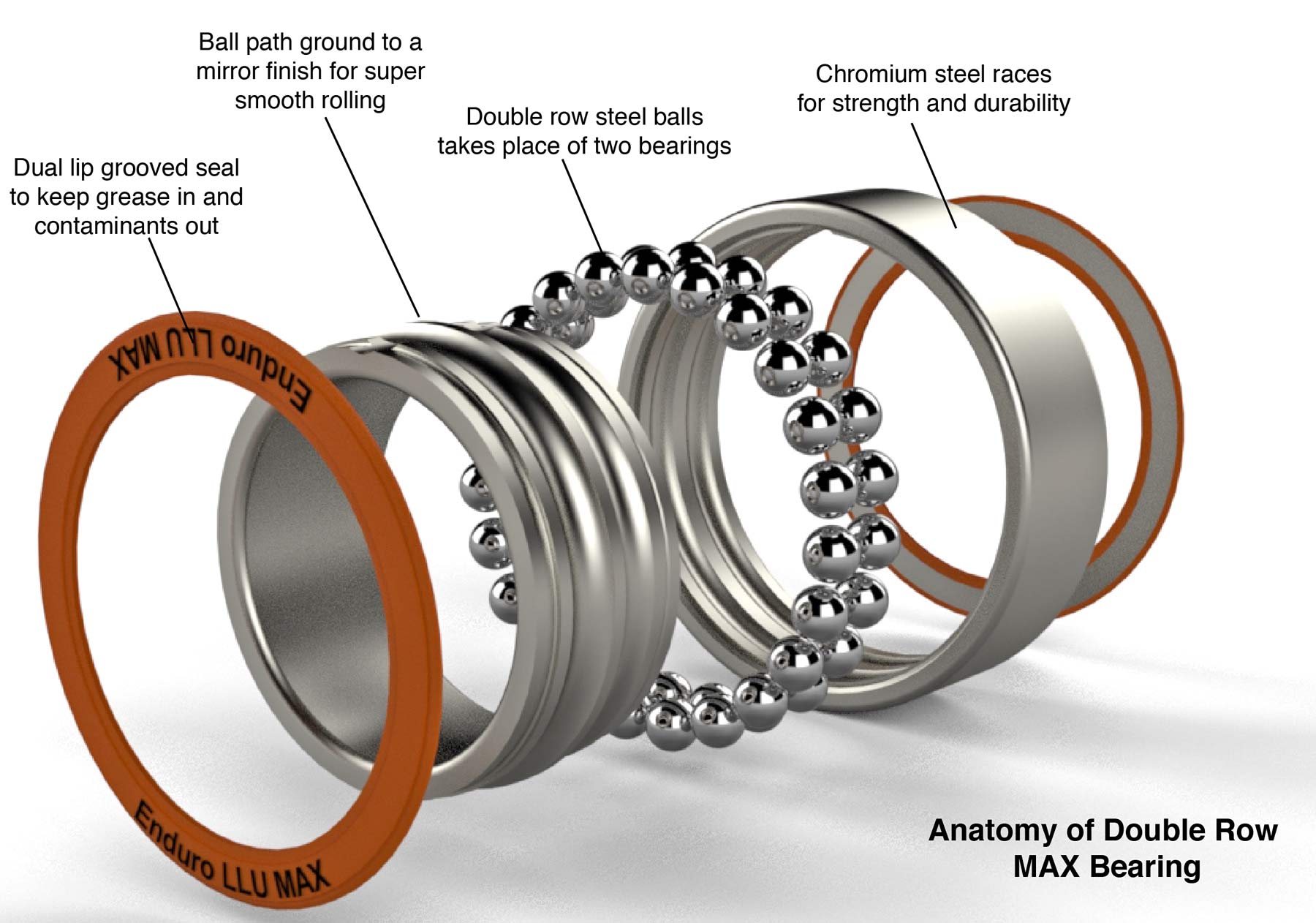

A ball bearing is the most common bearing we find in bike frames. It generally works by having tiny steel (or ceramic) balls rotating inside a pair of hardened races that contact your bike. In suspension frames they usually get pressed into a specific hole/recess in the frame and pivot around an axle. Bearings are ideal for elements that rotate a large degree (like a full 360° in a wheel or bottom bracket) and can be well protected from the elements with a series of seals.

At the same time that Ibis chose bushings, the new Rocky Mountain Instinct has dropped the ABD bushings of its previous generation in favor of sealed cartridge bearings. It’s true that the bike’s main pivot and rocker linkage pivots may move through a wider range of rotation than the Ripmo, the driving factor in the move to bearings here is probably more about sealing out the elements. With sometimes double, labyrinth seals, and packed with grease, bearings can be more resistant to riding in the wettest & muddiest climates.

So what does all this mean for the end user? Now that you have an idea of what makes your bike’s suspension pivot, we can start to talk more about how to keep it running smoothly for years of riding enjoyment, besides just keeping your bike clean. Each one – flex, bushings & bearings – requires its own maintenance methods to keep your rear wheel travel moving smoothly. The good news is that it isn’t too hard to keep each pivoting as it was designed.

The fun never ends. Stay tuned for a new post each week that explores one small suspension tech, tuning or product topic. Check out past posts here. Got a question you want answered? Email us. Want your brand or product featured? We can do that too.