Fox Factory has filed a patent titled “Suspension Enhancing Hub and Rear Derailleur Assembly”, outlining two separate but related inventions designed to eliminate the negative effects that chain tension exerts upon a bicycle’s rear suspension and ride feel.

A rear derailleur with an electronically actuated clutch mechanism deals with chain tension between the chainring and the derailleur, while an automatic electronic decoupling hub assembly deals with chain tension created between the chainring and the cassette. In the patent, both components are described as being controlled by sensors detecting important information about the ride, such as gradient, pitch of the bike, and suspension action, while the possibility of an “over-ride” is also described that could allow the rider on-the-fly control over the behavior of the components.

It’s a “no-comment” from Fox on this one, but we’ll certainly be keeping an eye out for these components come the opening round of the World Cup DH in Lenzerheide this May.

Fox Suspension Enhancing Hub and Derailleur Assembly: Context

Before digging down into the details of the two inventions described in Fox Factory’s patent, it is necessary to discuss why either may be necessary in the first place. So, you’ve all seen Aaron Gwin’s 2015 World Cup DH Run at Leogang, right? If not, go watch that then come back and read on.

Indeed, Aaron took the win despite losing his chain as he cranked out of the start gate. Not to take away from Aaron’s achievement that day, but it is no secret that dependent on the particular linkage design, the efficacy of a full suspension mountain bike’s rear suspension stands to benefit from the absence of a chain.

In the presence of a chain, pedal kickback can be experienced as a result of increasing rear-center length, particularly on bikes where the main pivot is not concentric to the BB; i.e. most of them. Simultaneously, along the lower chainline if you will, resistance is offered up by the rear derailleur as it extends during the suspension’s compression phase, particularly if that derailleur’s chain tensioning aspect has a clutch mechanism damping movement of the cage. Both of these phenomena are largely considered undesirable traits, particularly in the world of downhill mountain biking where suspension performance is paramount.

The Fox Factory patent discussed herein describes two distinct inventions looking to solve the aforementioned issues brought about by rear-center length changes occurring as the suspension compresses and rebounds.

Fox’s Electronic Automatically Decoupling Hub Assembly

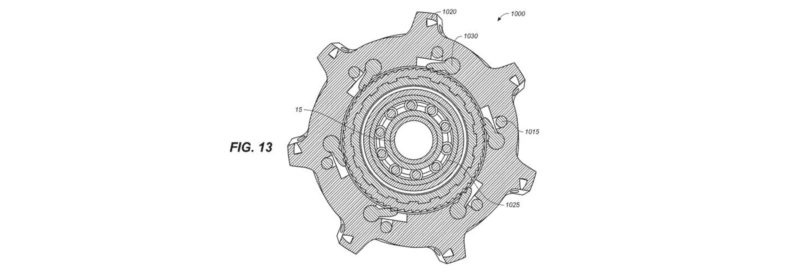

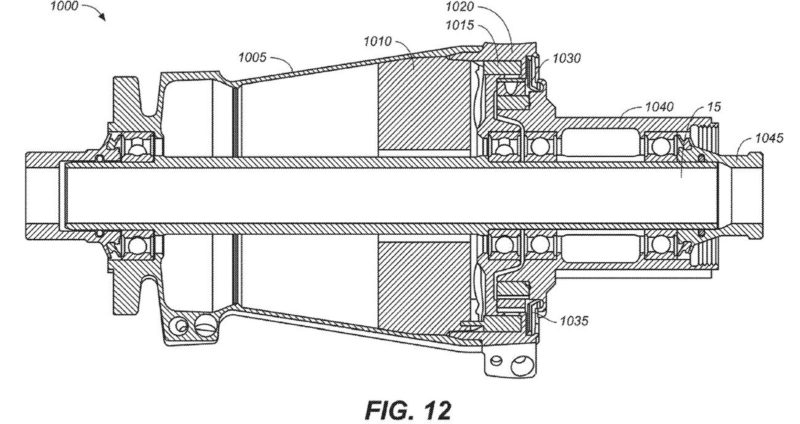

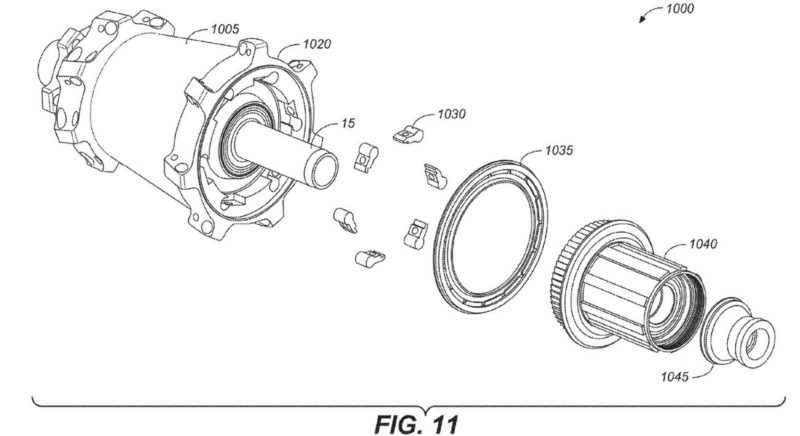

One of these components is an “electronic automatically decoupling hub assembly”. A set of pawls are housed within the hub, from where they can be forced to selectively engage or disengage with ratchet teeth housed on the freehub body (or cassette body) such that when the rider pedals, force is transmitted to the hub shell to drive rotation of the rear wheel. That unusual, sort of inverted arrangement appears to be necessary to the heart of this invention; the electronic control of pawl engagement.

While pawls are usually spring loaded, here Fox describes situations (or embodiments) where the engagement state of the pawls is determined by an electromagnetic circuit controlled by the inputs of a sensor or sensors distributed about the bike.

The patent document states, “In one embodiment, electronic automatically decoupling hub assembly uses magnets in each of the pawls with inductors/electromagnets above it and controlled by a controller inside the hub shell NDS. When not pedaling the pawls would be disengaged by the inductors/electromagnets turning on or flipping polarity to attract the pawls upwards away from the ratchet ring on the cassette body. When pedaling the inductors/electromagnets would be turned off and the magnets of pawls attracted to the ferrous ratchet ring (less energy usage). Or the polarity of the inductors/electromagnets could be flipped to repel the pawls away, forcing them toward the ratchet ring“.

It goes on to describe the potential benefits of having real-time control over engagement and disengagement.

“[T]he electronic automatically decoupling hub assembly could have a nearly infinite amount of automatic engagement and disengagement, in real-time, and throughout the ride. As such, the rider would have all of the normal suspension articulation during most of the ride and when different levels of violent suspension articulation events occurred, the chain pressure via the electronic automatically decoupling hub assembly would be reduced to ensure full suspension articulation while also minimizing the opportunity for a violent feedback through the pedals that would be transferred to the rider”.

Fox’s Electronic Disengageable Rear Derailleur Assembly

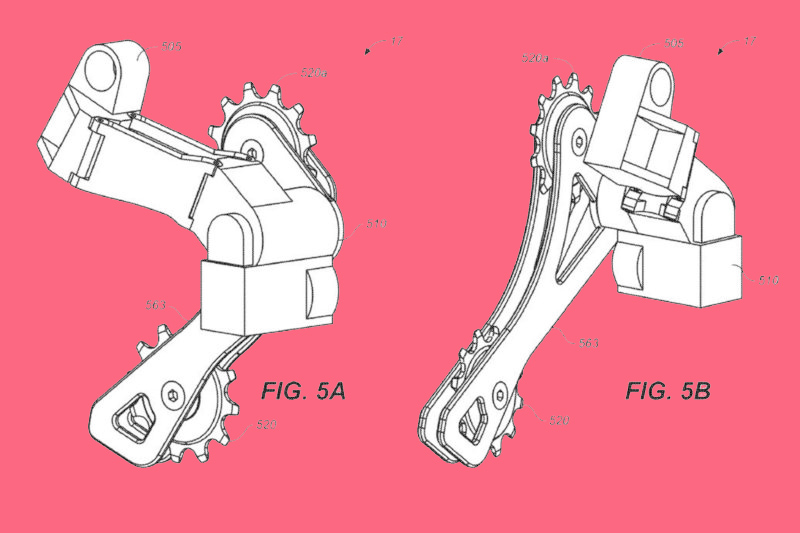

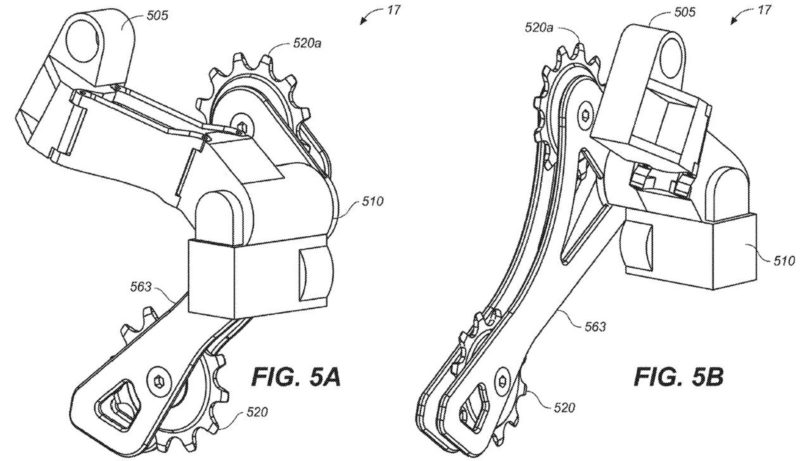

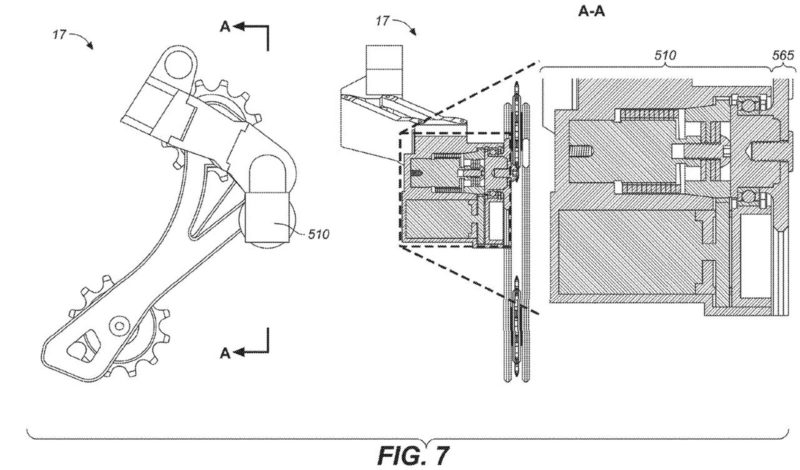

The second invention described within the patent is an electronically disengageable rear derailleur assembly. Figures published as part of the patent depict a derailleur with a mounting component, a parallelogram component for shifting through sprockets of the cassette, and a P-Knuckle housing a clutch mechanism that is coupled to a short-cage with an upper and lower pulley wheel.

The interesting components of this derailleur lie within the P-Knuckle. The Fox patent describes the P-Knuckle as housing a motor and gear, a spring (or solenoid) housing, a linear solenoid, a torsional power spring, a P-Knuckle clutch plate, at least one thrust bearing, and a P-Knuckle cover.

The “electronic disengageable” bit refers to the articulation of the derailleur cage about the P-Knuckle. It seems as though the electronically operated clutch mechanism within the derailleur can be selectively switched on or off, as decided by a controller processing information from various sensors on the bike.

“In one embodiment, disengageable derailleur assembly remains engaged under normal chain stay length changes such as suspension articulation due to pedaling, normal suspension travel issues, and the like. However, when a significant suspension event occurs, e.g., hitting a large bump causing a large, quick articulation of the suspension P-Knuckle assembly will not provide significant damping during the chain length extension”.

It makes a lot of sense to minimize the effects of chain tension during suspension compression, to allow the suspension to work its magic over rough terrain. However, the clutch on a derailleur is there for good reason; to stop the chain slack from increasing to a point where the chain is able to jump off the chainring. This is, of course, considered in the Fox patent too.

“Maintaining chain tension is important to maintain chain retention such that the chain does not bounce off a chain ring. However, the disclosed technology selectively engages and disengages the cage assembly from the P-Knuckle, such that the tension on the chain is relieved (due to the disengagement) when the chain growth is increasing. Moreover, (due to the re-engagement characteristics of the cage assembly with the P-Knuckle) tension is maintained when the chain growth is reduced or is no longer increasing”.

As any brand would, Fox is covering many, many bases with this patent, increasing its scope to include a version (or embodiment) of the disengageable derailleur assembly that is able to make use of the “wave dynamics” of the chain itself to manage frictional disengagement and re-engagement.

It reads, “disengageable derailleur assembly can actively, automatically, and continually adjust the position of P-Knuckle assembly with respect to the position of cage assembly based on suspension position and gearing such that the system will always have the correct amount of chain paid out. This would minimize chain slap and could eliminate load on the whole suspension system”.

Where is Fox going with this?

We contacted Fox to inquire about their intended use of this technology. As expected, “no-comment” was the reply. Thus, we are left to hypothesize.

An obvious application for this technology is in Downhill and Enduro Mountain Biking, where the scope for pedal feedback and chain tension to negatively impact a rider’s performance is relatively high. Indeed, multiple attempts have been made over the years to reduce pedal kickback. For example, OChain’s Active Spider has become popular on the World Cup DH Circuit; it allows for some dissociation of the chainring and cranks such that the cranks are not forced to rotate rearward during pedal kickback events, allowing the rider to maintain a “pedals level” position.

I digress. It is interesting to note that while much of this patent document details the use of sensors and processors to control the operating state of the decoupling hub assembly and disengageable rear derailleur, the possibility of an “over-ride” is also mentioned. This indicates a possibility that the two components could also conceivably be controlled by a remote operable on-the-fly by the rider if mounted on the handlebar.

One can imagine a scenario wherein the rider would be able to switch between two pre-set drivetrain states, dependent on what kind of terrain they were about to charge into. Come the start of the 2023 World Cup DH Season, we will be keeping an eye out for anything of the sort.

Ultimately, it seems logical that control of the electronic automatically decoupling hub assembly and electronic disengageable rear derailleur assembly described in Fox Factory’s patent would be integrated into the Fox Live Valve ecosystem wherein suspension damping is automatically and electronically adjusted in real-time.

Given that those suspension components house accelerometers and other sensors monitoring the bike’s state, it isn’t too wild to suggest that those same sensors could deliver information to a processor to also make decisions on the appropriate state of operation for the decoupling hub assembly and disengageable derailleur assembly. After all, the Fox Live Valve electronic compression damping system is being asked to monitor the terrain 1000x per second and to make adjustments based on that information within 3 milliseconds. That’s 100 times faster than the blink of an eye!

Finally, given that current suspension linkage designs must take into account the presence of chain tension, it’s possible that successful implementation of the Fox Suspension Enhancing Hub and Derailleur Assembly or components to that effect could have huge implications for how frame engineers design full suspension mountain bikes in future.

As ever, you’ll have more information on Fox’s Suspension Enhancing Hub and Derailleur Assembly when we do!