Earlier this year, Hope Technology announced the all-new Hope HB916 Enduro Bike. It is unashamedly a thorough-bred race machine, as demonstrated by Joe Barnes on the World Enduro circuit. A “semi” high-pivot four-bar suspension platform delivers 160mm of rear wheel travel, with a majority rearward axle path on a slacked-out carbon frame with generous reach and wheelbase numbers. And it gets a butty-box, where one can safely stow one’s butties (sandwiches, not tiny friends) during one’s weekend of shredding.

It’s easy to see the appeal, right? The HB916 is bang-on-trend, and it looks like an absolute weapon. And it’s made entirely in the UK at the Hope Tech HQ in Barnoldswick. I was excited to try it out on Scotland’s finest.

All photos courtesy of Finlay Anderson, unless otherwise stated

Hope HB916: An Overview

We first got a good look at the Hope HB916 at CORE Bike where it was unveiled for the first time with three jaw-droppingly gorgeous framesets on display. You can pick up the Carbon Finish frameset with either a Ohlins TTX22M Coil, Ohlins TTX2 Air, Fox DHX2 Coil, or Fox Float X2 Air Shock for £3,595 / €4,500. That includes a Hope Headset and T47 Bottom Bracket.

The Neutral Finish (Black and White) will cost you a little more at £3,845 / €4,800, with the Chameleon Finish the most expensive option at £4,095 / €5,100. Like a chameleon, it changes color depending on how the light hits it, and you can still see the carbon finish underneath. It’s kind of fabulous.

We covered the full details of the Hope HB916 previously. Before I dive into my impression of its performance on the trail, it is pertinent to give a reminder of the need-to-knows.

- Intentions: Enduro Racing

- Fork Travel: 170mm

- Rear Wheel Travel: 160mm

- Wheel Size: 29″ or 29″/27.5″

- Size Options: H1-H4

- Frame Material: Carbon, bonded to aluminum yokes with an aluminum rocker

- Shock: 205mm x 65mm

- Actual Weight: 15.14 kg (H1 in 29″/27.5″ without pedals)

- Frameset Price: From £3,595

- Complete Bike Price: £6,745

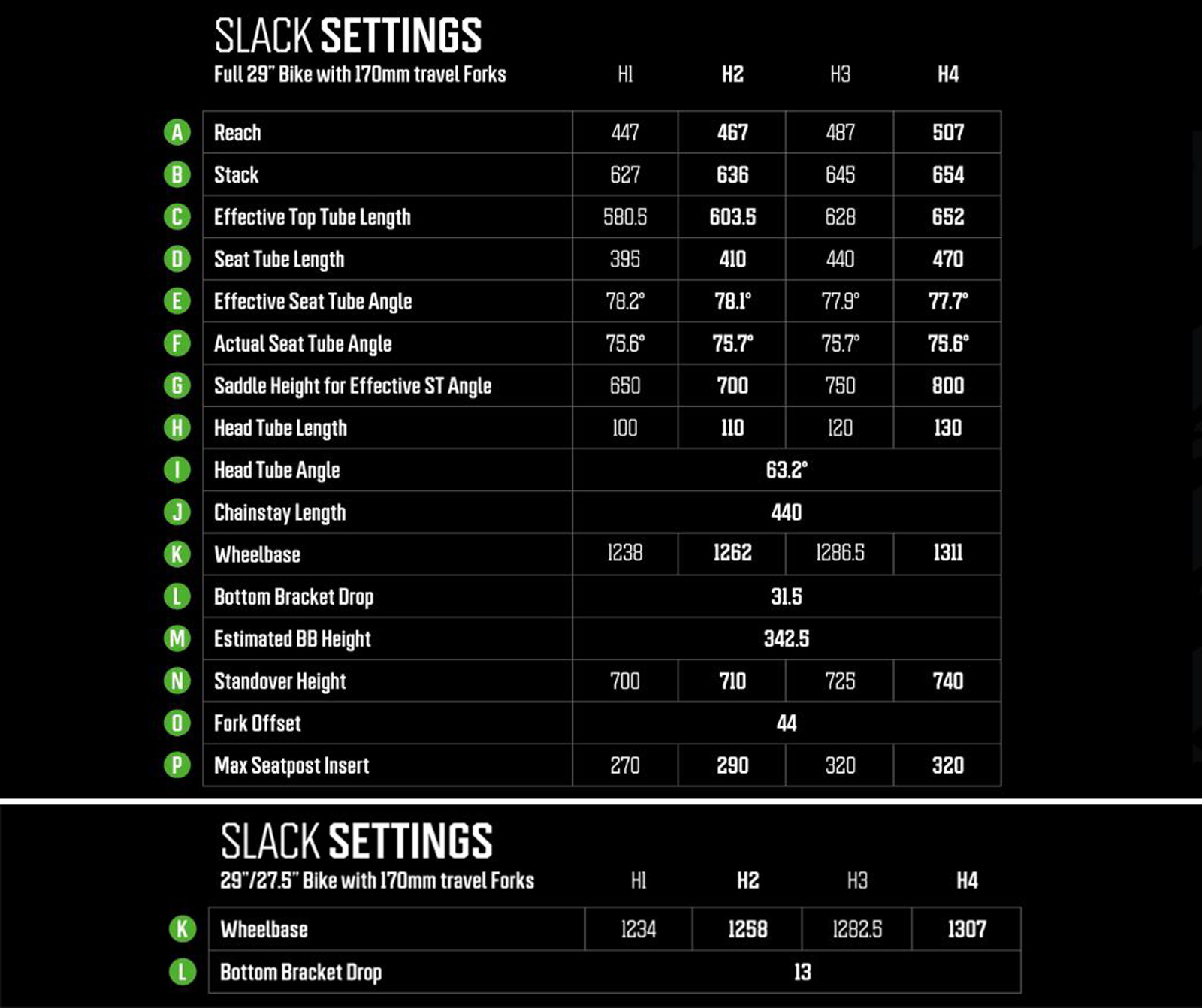

With a 170mm travel fork and a 29″ wheelset, the HB.916 has a 64° head angle and a reach of 470mm in H2. But, thanks to adjustable headset cups and a flip-chip at the rocker-seat stay interface, this enduro bike has no fewer than four setup configurations. The former allows the head angle to be slackened off to 63.2°, while the latter corrects the bike’s geometry when the 29″ rear wheel is switched out for a 27.5″ wheel. Thus, you have four geometry charts to pore over.

Carbon seat and chainstays are bonded to aluminum yokes. Hope chose to construct the bike in this way so that most of the frame bearings can be housed within the CNC’d aluminum rather than within the carbon which is more liable to wear after multiple bearing replacements.

The only location where frame bearings are pressed into carbon is at the rear pivot that sits concentric to the rear axle; this is due to packaging constraints. Here, Hope machine the bearing size rather than mould it to ensure a good fit and reduce the risk of any damage and wear through use.

Thanks to the flip-chip, the only noteworthy geometry change arising from the switch to a mullet configuration is the 4mm shorter wheelbase. Of course, the BB drop is reduced as well, given that the rear axle is now much closer to the ground.

The bike’s seat tube length is short across the H1-H4 size range, allowing for the fitment of long-travel dropper seat posts. For example, the H1 that we tested gets a 395mm seat tube but has sufficient insertion depth to run a 180mm dropper from OneUp Components. Spoiled or what?

All sizes feature 440mm chainstays. The rear-center length actually increases as the bike is pushed through its travel. That’s thanks to the main pivot location being a fair bit higher than what is commonly seen on a four-bar linkage enduro bike.

When set up as a complete 29er, the rear-center grows by 9.5mm during the first two-thirds of the travel, then begins to shorten again as the arc sends the rear axle forward by around 4mm to bottom-out. Thus, at bottom-out, the rear-center length is 5.5mm longer than it is in the unloaded state.

In its mullet configuration the rearward axle path is exaggerated, with the rear-center growing by 13mm before the arc tracks a forward thereafter.

It should be pointed out, though, that the Hope HB916 isn’t the most aggressive of high-pivot bikes, in that its main pivot isn’t actually all that high. Bikes like the Deviate Claymore and Actofive P-Train 165 have much more dramatic rearward axle paths. Engineer, Sam Gibbs, tells us that Hope’s “semi” high-pivot bike makes for a more balanced ride feel when you’re really hammering on, helping to keep the rider’s weight centered on the bike.

I digress. On the drive side, you’ll see the addition of an idler pulley that routes the chain closer to the main pivot to reduce undesirable pedal kickback brought about by the chain growth that would otherwise be a drawback of this linkage design.

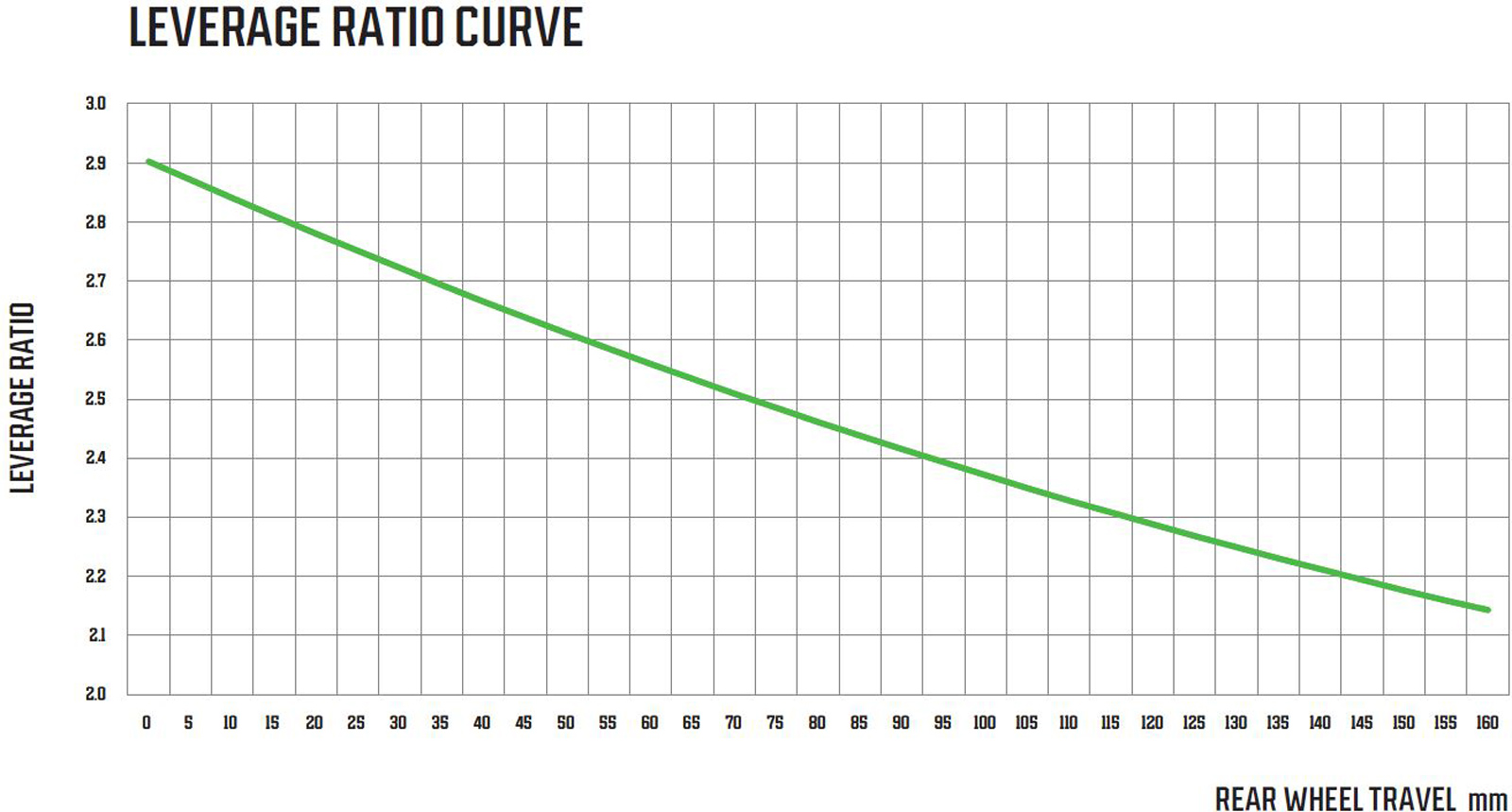

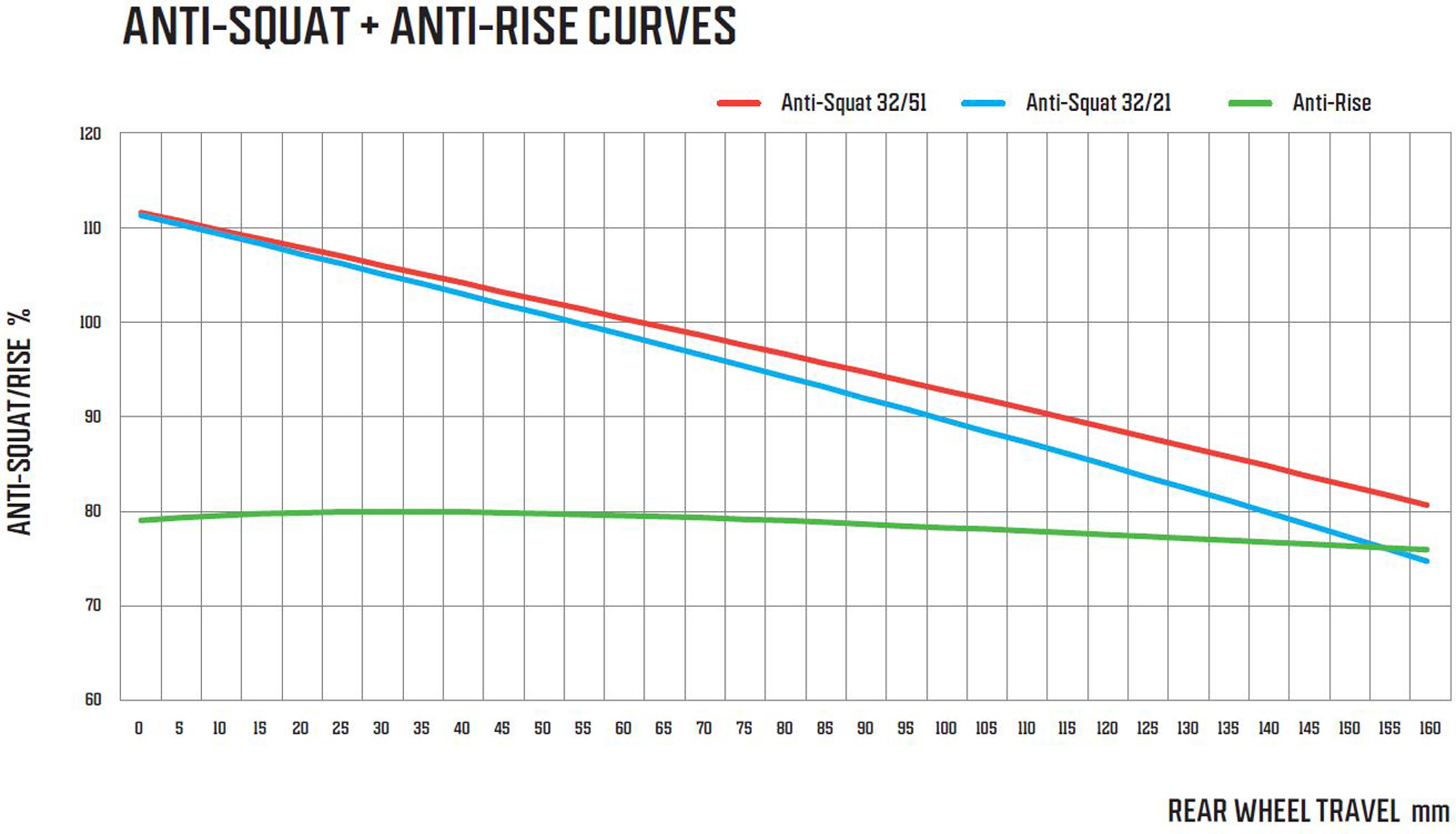

Sam also tells us that the bike was primarily designed to run a coil shock rather than an air shock. The overall progression comes in at 26% in the 29er configuration, and 27% when set up as a mullet; he says they took that as far as they could while keeping the suspension platform compatible with an air shock. The leverage curve, anti-rise and anti-squat graphs can be found at the foot of this article.

By now, you must be wondering how the thing actually rides…

Review

At 5ft 4″ tall (163cm), I was handed the Hope HB916 in the H1 Size. It is one of the longer bikes I’ve ever ridden, and I was a little concerned its 447mm reach would be a stretch too far. Hope say the H1 is good for folk from 162cm tall, so I threw caution to the wind and accepted the offer of a test bike. And i’m ever so glad I did. I needn’t have been worried; the bike’s 78.2° effective seat tube angle positioned me in a commanding position over the BB, within a comfortable reach of the bars which I cut down to 740mm to suit the narrow tree-lined trails the Tweed Valley is known for.

The HB916 is one of the better high-pivot mountain bikes in terms of its pedalling efficiency. In that department, it compares favorably to the GT Force and the Cannondale Jekyll, two bikes with high(ish) main pivot suspension platforms that also necessitate the use of an idler pulley. It’s quieter, too. The idler itself has 18 teeth, which is quite large, likely helping to minimize any efficiency losses.

On long uphill fire road slogs, the HB916 certainly feels efficient enough, and I never felt as though I was having to work any harder than usual. Weight will of course play a factor, and it compares favorably here, too. Without pedals, the H1 I tested weighed in at 15.14 kg in the 29″/27.5″ configuration – not bad for a lengthy 160mm travel enduro bike.

Under power, the bike shows no signs of squat. In fact, applying torque to the pedals in any gear actually pulls the bike out of its rear wheel travel, extending the rear shock. Rather than being neutral while climbing, the bike seems to bob ever so slightly, but only between sag and top-out.

That’s in contrast to the squat that is fairly common on bikes of this category, wherein the application of torque and the resulting acceleration of the bike would drive the bike into its travel a little, making it feel wallowy and inefficient. That’s not the case here. I felt the HB.916 was a more efficient climber than the Vitus Sommet 297, but less efficient than the SCOR 4060 LT which has an impressively firm pedaling platform. I choose to mention these bikes as I have tested them very recently.

My first few rides on the HB916 were with a complete 29″ wheelset, with the headset cups oriented in the slack setting. For technical climbing, the 63.2° head angle was far from ideal. However, most of the climbing around the Tweed Valley consists of long drags up smooth fire roads, so I never felt the need to re-orient the cups to the steeper setting. Also, this bike is very much about going downhill, not up, and I was more than happy to spend the last month or so aboard something super slack.

I set the bike up with around 31% sag in the Ohlins TTX2 Air shock, and went with the manufacturer’s recommendation for the Ohlins RFX38 Air fork. The stack height was far too tall for me so I dropped the stem to almost the bottom of the stack. The fork was a little over-damped for me, despite running compression and rebound fully open, so I dropped the pressure in the main chamber and the ramp chamber in a bid to use more of its 170mm travel. That worked well for my local tracks.

I was really happy with the rear suspension’s small bump sensitivity and its seemingly magical ability to patter through almost any rock garden with little to no drama. However, at 31% sag, I felt the bike was a bit lazy, unresponsive, very much wanting to stay firmly on the ground.

In a bid to make some improvements, I increased pressure in the rear shock to bring the sag to around 27%. Here, the bike was so much livelier, and way more enjoyable to ride. It was impressively light-footed, now effortless to pick up for the small natural gaps that litter our plantation forest trails. I wouldn’t say it has bags of playfulness, but it was still an absolute joy to ride on some of Aberdeenshire’s new flow trails where the bike is rather overkill.

You may have read elsewhere that high-pivot bikes can be a bit unpredictable on jumps, due to the rearward axle path; that’s not consistent with my experience of the HB916. To me, it feels the same as any other enduro bike to jump. That said, i’m not exactly Sendy McSenderson, and my jumps rarely go beyond the basic trail center double.

Riding some of the Tweed Valley’s steeper enduro trails, it soon became evident that the complete 29″ setup wasn’t ideal for me. Tire buzz became a problem, so I switched out the 29″ rear wheel for the 27.5″, switching the orientation of the flip-chip at the seat stay-rocker interface; that was a super easy, straightforward process that took mere minutes with the bike in a stand.

With the new reduced-sag mullet setup, tire-buzz became a thing of the past and I felt truly at home on the bike. On some of the faster, chunky rock-strewn trails, the Hope HB916 simply feels like cheating. It patters through at speed, with the rear wheel tracking super smoothly over the rough stuff. I was up to race pace very early on. The bike is quiet and comfortable when pushing on, with no nervousness to speak of. It just feels safe; that may sound a bit boring, but it’s quite the opposite when you realize you’re at race pace but still but still well within your comfort zone.

In tightly-spaced bermed up corners, the length of the bike did require me to be a little more dynamic than i’m used to. It was cool, though; I felt there was heaps of space available within the cockpit for bike-body separation, thanks in large part to the generous reach and the 180mm travel dropper post from OneUp. I felt seriously spoiled by the latter, having become used to the 125mm and 150mm dropper posts that are more common on small bikes.

The rear-end was plenty supportive, offering up plenty to push against at the apex of turns when demanding grip from the tires.

A trip to Aberdeenshire for the Scottish Mountain Bike Conference highlighted some inadequacies with the setup I had dialed in for the Tweed Valley’s enduro race tracks. Many of the tracks in that region of Scotland are composed primarily of granite rock slabs; they are faster, and generally require a firmer setup, as demonstrated by the multiple bottom-out events I was experiencing on each descent.

To remedy that, I simply increased the pressure of the fork and the shock. I was now running only 23% sag in the rear shock, which left the bike feeling a little nervous and harsh on some of the rougher, rockier trails. An additional volume spacer would have been a better fix, but I didn’t have access to one whilst on the road.

Ultimately, the HB916 is easily the best enduro bike i’ve ever had the pleasure of testing. Certainly, the best enduro race bike. I’ve ridden more playful, better-pedalling offerings, but none so confidence-inspiring and easy to ride fast as this one. I’m putting my money where my mouth is and making the purchase.

What about the butty-box?

Not much to say on that, unfortunately. The bike I tested was incomplete in that the hatch was simply a portal into the depths of the downtube. The production bikes will have a discrete compartment with some kind of bag that should help prevent any contents from rattling.

A peek underneath the hatch did reveal the cable routing, however. It’s not a fully guided tube-in-tube job, but there are foam guides that run the length of the downtube, interrupted only by the CNC machined grommets that secure the cables in position and further prevent rattle. It seemed to do the job, as did the drive-side chainstay protection, as the bike was impressively quiet on the trail.

Pros

- Well-balanced

- Quiet

- Feels safe to ride fast

- Stable but with good responsiveness

- Meaningfully adjustable

Cons

- Lead-time of 8 months

- SRAM UDH, but NOT compatible with Transmission derailleurs

HB916 Test Bike Spec List

- Frame: Hope HB916 H1, One-Piece Carbon Front Triangle, Carbon Seat Stays and Chainstays with CNC Machined Aluminum Yokes and Rocker; Boost Spacing, SRAM UDH, T47 Bottom Bracket

- Fork: Ohlins RXF38 Air

- Shock: Ohlins TTX2 Air

- Wheels: Hope Fortus 30SC Aluminum Rims on a Hope Pro 4 hubset

- Tires: Maxxis Assegai EXO+ MaxxTerra 29″ x 2.5″, Maxxis Minion DHRII EXO MaxxTerra 27.5″ x 2.4″

- Drivetrain: SRAM GX Eagle Cassette, Derailleur and Shifter with Hope Evo Crankset (175mm)

- Brakes: Hope Tech 4 Levers with V4 Calipers

- Seat Post: OneUp Components V2 Dropper (180mm)

- Stem: Hope Gravity 35mm Clamp, 50mm Reach

- Handlebar: Hope Carbon Bars 740mm x 35mm

- Grips: DMR Deathgrips

- Pedals: Hope F20 Flat Pedals

- Saddle: WTB Volt (swapped out for an Ergon SMC Womens Saddle)

- Actual Weight: 15.14 kg without pedals

- Price: £6,745