It’s 2019, and you’re shopping for a road bike. Maybe you’re new to the scene of “serious” cycling and are buying your first road bike that costs $1,500 or more. Or perhaps you’re a veteran cyclist that hasn’t upgraded in a decade and you’re just out of the loop. If the terminology you’re seeing looks like a foreign language mixed with marketing hype, you need this quick guide to bring you up to speed on the current state of road bikes – a 10,000ft view that won’t cover every possible brand or product, but rather a Cliff’s Notes version so you won’t make any bad purchase decisions. If you want to future-proof your investment as much as possible, this is your Road Bike Buyer’s Guide!

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- The State of the Union

- Hub Axle Standards

- Bottom Bracket & Crank Standards

- Number of Chainrings and Cogs

- Gear Shifting Methods

- Brake Types and Trends

- Wheels & Tires

- Freehub Standards

- Cockpit Standards and Trends

- (Micro) Suspension

- Fork Standards

- Frame Geometry

Quick note: If you’re buying a complete bike, this overview will help you know what to look for and ask about. You won’t necessarily need to remember everything, but this should provide the basis for picking something that has all of the latest standards. Or, at least, those standards that are important to you. This is especially important if you’re buying a lower priced bike now with plans to upgrade. Some standards are more easily upgraded than others. And if you’re building your dream bike component by component, then pay attention to the details because not everything plays well together. Ready? Here we go.

1. STATE OF THE UNION

For purposes of this article, we define a road bike as something featuring drop handlebars and primarily intended for riding on paved surfaces. It’s not an aerobar-laden time trial bike, and it’s not a fat(ish)-tire cyclocross or gravel bike.

Over the past 10-15 years, road bikes split into several sub-categories – aerodynamic road bikes, endurance road bikes, ultralight climbing bikes, crit racing bikes, and so on. These are all based around the same basic platform, with differences in construction and geometry to better suit the specific task at hand. As the retail price of a bike decreases, the number of different frame types tends to decrease as well (i.e. you’re not likely to find a budget-oriented climbing bike, due to the high cost of specialty lightweight parts). But like all things, trends trickle down over time, too. The Look 785 Huez is a great example of this.

At the high end, we’ve reached the practical limit of light weight frames. Most major brands have settled in with a ~790g to ~900g frame as their “lightweight” bike. The real trend is in taking the disparate aero, lightweight and endurance models and combining the best traits from each into more capable, all-around bikes that are still race ready. Like the Trek Madone.

Lastly, two new trends have quickly settled in as near-standard equipment: Disc brakes and wider tires. Road bikes have traditionally featured skinny tires (i.e. 18-25mm wide), but this is quickly changing. Current norms range from 23mm to 30mm. Beyond that you’re in gravel and cyclocross territory. And while you’ll still find rim brakes, discs are becoming the future. The funny (or confusing) thing about these two changes is that they have caused a cascade of other changes throughout the bike, wheels and components. But don’t worry, we’ll explain it all…

2. HUB AXLE STANDARDS

For decades, quick release skewers were the standard for attaching wheels to a road bike. These simple devices are clever and effective – opening and closing with a single lever and no tools. The front axle spacing (i.e. width from one face of the axle to the other, a.k.a. O.L.D. or over-locknut distance) is 100mm, while the rear has been at 130mm for about 25 years. This worked great until disc brakes came along…

Disc brakes are bringing two key axle-related changes to road bikes, both of which have been proven on mountain bikes. So they’re not new standards, just new to the road. The first disc brake road bikes kept the 130mm hub spacing, which resulted in narrow hub flanges. Then we moved to 135mm spacing, which added a bit of room, but pushed the cassette out slightly and messed with chain lines, degrading shifting performance. The quick solution was to make longer chainstays, but now we’re seeing a more holistic approach between frame and drivetrain makers, so any new disc brake road bike has likely solved for this and will have the shifting performance you expect.

Any new disc brake road bike is also likely coming with thru axles – don’t buy a QR dropout disc brake road bike in 2019, because it’s already outdated. Thru axles feature a larger diameter than quick release skewers, boosting stiffness – typically at little to no weight penalty. They improve handling and reduce flex, especially for powerful riders and rough conditions. As an added bonus, they position the wheel more consistently during wheel swaps, which ensures perfect brake rotor alignment. They’re also safer because there’s little chance a thru axle will accidentally open or come out.

Front thru axles for road bikes have largely settled on 12x100mm – meaning, 12mm diameter axle with a 100mm wide hub shell. So, the width hasn’t changed from quick-release wheels on the front. Mountain bikes mostly use a 15x100mm front thru axle, and you might still find a few road bikes that adopted that standard early-on – but 12×100 is more future-proof for road. Some wheels and forks have swappable end caps or dropout inserts allowing for the use of either 12 or 15mm front thru axles. Sorry, but the old road wheels hanging in your garage are probably not adaptable to thru axles (though you might get lucky – check with the manufacturer).

Rear thru axles for road bikes are either 12x135mm or 12x142mm. The former was really a stop gap as road bikes were figuring out thru axles, and the latter has become favored standard. The takeaway? If you go disc, make sure it has 12×100 and 12×142 thru axles.

But aren’t there different thru axle types?

Why yes, there are.

Some thru axles are bolt-on style, either with or without a lever, and sometimes with a removable lever. Others thread in to the frame or fork on one side, and secure using a lever that’s modeled after the good ol’ quick release skewer. Note that there are quite a few different thread pitches and designs of front and rear thru axles (i.e. your 12x142mm rear axle might not fit my bike that’s also equipped with a 12x142mm rear thru axle, because the size of the threads may be different). It gets complicated. When in doubt, only use the axles that came with your frame and fork – and keep spares handy if you’re prone to losing small parts.

To complicate-but-also-simplify the situation, Mavic has their SpeedRelease Thru Axle system, which solves a problem for the pro peloton’s need for quick wheel changes. This works with any 12mm thru axle hub, but it does require the frame and/or fork are made to work with it. There are compatible bikes on the market (Look, Cannondale, Alchemy, to name a few), and the design is open to be licensed by anyone, so you may see other brands come on board in the future.

Will a thru axle bike fit on my indoor trainer?

Thru axles often require the use of adapters in order to attach your bike to an indoor stationary trainer, a fork-mount workstand, or a roof rack for your car (though modern versions of these continue to do a better job accommodating the different thru axle sizes and styles). The wisest thing you can do is bring up this topic during the bike purchasing process, to bundle any necessary adapters with your bike purchase. There are also some cool companies like The Robert Axle Project specializing in making a host of specialty thru axles to serve any need – indoor trainers, BOB trailers, and more.

3. BOTTOM BRACKET & CRANK STANDARDS

Ever the source of controversy, all your bottom bracket really does is keep your cranks spinning when you pedal away. If you’re a cycling veteran, you can rest assured that English threaded bottom brackets (also called BSA, BSC, and ISO) are still around. We wrote a bottom bracket update in 2010, but since then the landscape has changed, a lot.

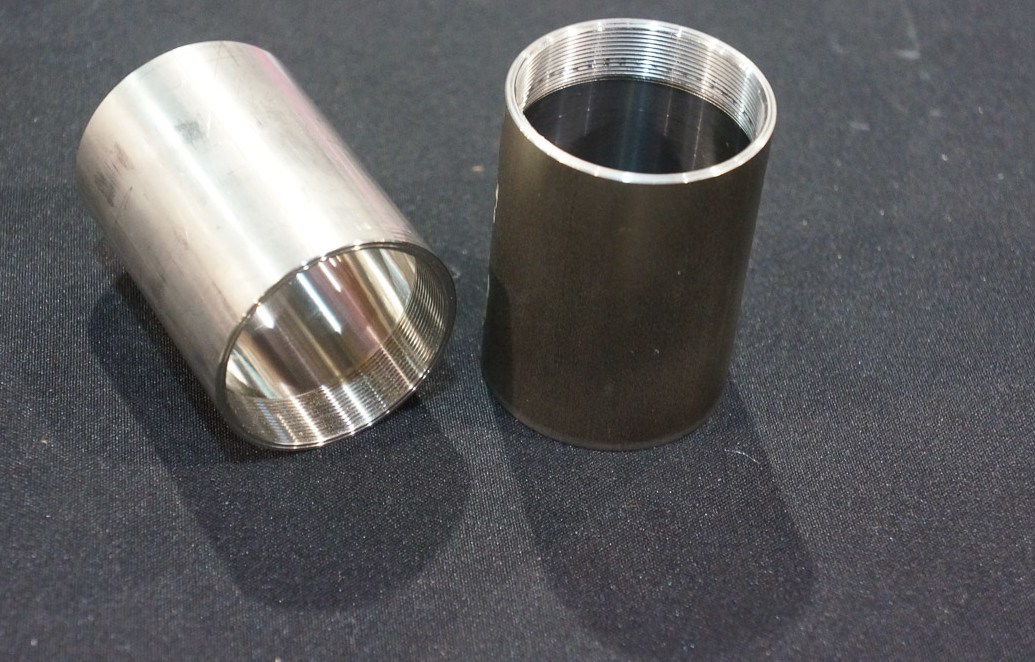

Today, the two broad categories that you’ll find are 1) threaded and 2) press-fit bottom brackets. Most threaded road bottom brackets use a 68mm-wide shell with a standard threaded left side and reverse (left-hand) threaded right side. You can thread in a square taper bottom bracket, or one of the more modern outboard bearing types, which rely on a crankset featuring its own integrated axle/spindle. Outboard bearings (seen below) were introduced in the early 2000’s, largely use a 24mm steel axle, and became the standard for anything but true entry-level bikes – which still often use square taper bottom brackets.

Press-fit bottom brackets are a large category containing many different sub-types. Rather than threading into the frame, they rely on a large bearing press for installation. The main reasons for their introduction were to reduce weight and increase stiffness via larger-diameter 30mm spindle. But, also, they speed up complete bike assembly at the factory, which is likely what truly drove their quick adoption. Here are some of the most common varieties:

BB30: Uses a short-length 30mm aluminum axle; bearings press directly into the frame (ideally into an aluminum insert molded into a carbon frame, since it’s not ideal to press bearings directly into carbon fiber). It’s rare to find a true BB30 frame anymore because PFBB30 is better.

PF30 / PFBB30: Same as above, but the bearings are pre-pressed into a plastic or nylon sleeve that presses into the frame. Typically results in easier installation and easier/cheaper frame manufacturing – no precision-machined aluminum insert required. The composite cups that hold the bearings can make up for minor frame intolerances, and they help minimize the creaking that could occur in a BB30 setup.

BB86 or PFBB86: Relies on a slightly smaller bottom bracket shell than PF30, using a bearing size intended for a 24mm steel crank spindle (which would otherwise be used with a standard threaded bottom bracket shell and outboard bearing bottom bracket).

BB386EVO: A newer standard that claims to offer a “best-of-all-worlds-and-compatibility” for future-proofing. Originally, road bike bottom brackets were sized around a 68 (or sometimes 73mm) wide standard. BB386 pushed this out to 86mm, the idea being to allow frame manufacturers to create wider, stiffer bottom bracket sections to improve power transfer. This required a longer crank spindle, which was called BB386EVO. While some frames require a BB386 crankset because they have the wider BB shell, a BB386 crankset will usually also work in a BB30/PF30 frame by adding spacers.

There are others: Trek’s BB90, Cervelo BBRight, Specialized OSBB, and more. If you’re glazing over with confusion and boredom, the good news is that companies such as Wheels Manufacturing, Rotor, Praxis, and others have created adapters and special bottom brackets which allow many of these different crank, bottom bracket, and frame standards to play nicely with each other. Be aware that Cannondale’s Ai asymmetric frame designs and bottom bracket layouts sometimes have very limited upgrade options…but they also make some very lightweight, high end SiSL cranks, too, so that’s only an issue if you absolutely must run a complete Shimano/SRAM/Campagnolo group. In general, the best way to future-proof yourself with an expensive crankset or crank-based power meter purchase is to buy an option with a long crank spindle. You can always use shims or adapters to take up extra spindle length, but you can’t make a too-short spindle work in a wide frame.

And then there’s T47: The other new story is that there’s a new threaded bottom bracket standard that came to the scene in 2015, and attempts to combine the benefits of large diameter press-fit axles with the ease of threaded bottom brackets – called T47. In short, it uses the same threaded style as an old BSA bottom bracket, but in a larger diameter that fits BB30-style bearings and cranks inside. While it hasn’t gained widespread adoption yet, it could be a popular future standard that retains backwards-compatibility. So, if you see this as the standard on whatever bike you’re looking at, that’s a good thing.

The Takeaway: Most 2019 road bikes are shipping with PF30 or BB386, and that’s fine. For many riders, they’ll work great. And if you do start developing any play or creaking, upgrade to a thread-together bottom bracket that adds a few grams but mostly eliminates any of the creaking or misalignment issues of press-fit designs. Or check out the one-piece solutions from BBinfinite, which seem to spin for days.

4. NUMBER OF CHAINRINGS AND COGS

Even if you’ve been away from cycling for a long time, you probably know that it’s par for the course for manufacturers to increase the number of rear cassette cogs every ~five to eight years. For 2019, most mid-to-high-end road bikes will have 11 cogs in the rear, and 10-speed has trickled almost all the way down. If you’re shopping at a department store, you might still find a 3×8, but virtually everything in a bike shop is now 2×10 or 2×11.

But if you’re looking for the best, 2×12 is already here and growing. Campagnolo introduced 12-speed rear shifting last year, and we expect Shimano and SRAM to probably follow suit before the end of the year. For future-proofing purposes, it’s safe to assume that you should buy the highest number of rear cogs that you can afford.

It’s also worth noting that the switch from 10 to 11-speed road components required a new, longer freehub body to accommodate all those gears – at least for SRAM and Shimano components. We will cover this in greater depth in the Wheels & Freehubs section, but be aware that upgrading your current bike to the latest drivetrain may require new or rebuilt wheels, too.

While the number of cogs at the rear of our bikes steadily grows, the number of chainrings has slowly declined. Why? That larger number of rear cogs allowed the gear range to grow – requiring fewer gears up front to maintain an acceptable range overall. In short, a system with two chainrings and eleven rear cogs could easily have the same or greater range than a system with three chainrings and nine rear cogs. It’s science.

This situation has caused a sharp decline in the availability of triple chainring drivetrains, leaving double (or “2x”) systems as the most common offering for road cycling. We now even have some single chainring (or “1x”) road drivetrains, which rely on a very wide range rear cassette to maintain an acceptable gear range. They’re even starting to show up as OEM spec with bikes such as the 3T Strada. The limitation of these cassettes is that they result in larger changes in gear ratio from cog-to-cog, which can cause difficulty in pedaling at a consistent cadence (an unwanted issue for some, but not all athletes). Single chainring systems make the most sense in flat terrain, and may gain popularity as more 12-speed systems emerge. If you ride in hills, though, a 2x is still the best option and won’t be going away anytime soon.

5. GEAR SHIFTING METHODS

Once you’ve selected the number of chainrings and rear cassette cogs you want, the next step is to decide how you’d like that shifting to happen. There are three current methods of actuating a gear shift:

- Mechanical

- Electronic

- Hydraulic

Mechanical systems are still the most common. Your shifter pulls on a steel cable, which runs along your frame through a cable housing, and eventually pulls on a derailleur – and the magic of shifting happens. Mechanical drivetrains are all made for different budgets, typically offering lighter weight and improved shift quality as you climb the ladder of price. The downside is that the shift cables and housings eventually become gummed up with dirt and debris, requiring their replacement. If you’re a cycling vet, the old familiar product names are still around – Shimano Dura-Ace and Campagnolo Record (and Super Record) continue their decades-long heritage as the premium groups. SRAM Red is now right there with them, offering a unique single-lever shifting option called DoubleTap.

Electronic shifting, on the other hand, is much newer to cycling. First introduced in the early 1990s by Mavic, it took almost two decades before electronic shifting hit mainstream cycling. Rather than relying on cables to move those derailleurs, each derailleur has its own electric motor.

The benefits of electronic shifting are many. It shifts very consistently, and there are no cables and housings to collect dirt and degrade shifting over time. It requires very little skill to use, and very little effort from your hands to shift. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it has opened up a world of customization and possibilities with software: customized button functions, automatic front derailleur trim adjustment, and multiple shift button locations.

What about downsides? First and foremost, electronic shifting comes at a premium price. While this will continue to trickle down to lower price points, it is far from hitting entry-level. Second, while you don’t have to replace shift cables, you do have to charge one or more batteries – the frequency of which depends on the system you buy and how often you ride (but count on every 1 – 3 months, give or take). Finally, while perhaps subjective, it can be difficult to diagnose or fix problems for the shade-tree mechanic, who is more accustomed to adjusting a cable than updating firmware.

The other choice to make when deciding on an electronic system is whether you want wired or wireless. Currently, the electronic systems from Shimano and Campagnolo are wired, while SRAM’s eTap is wireless. In other words – Shimano Di2 and Campy EPS systems have a physical connection running from the shifters to a single battery to the derailleurs. In contrast, each SRAM eTap component has its own battery (each shifter has its own replaceable coin cell battery, each derailleur has its own rechargeable battery), and shift signals transmit via a wireless signal. Debate about superiority rages on, but the short of it is this: Proponents of wireless shifting praise its clean look and quick installation, while proponents of wired shifting praise its longer battery life and its (theoretically) more reliable hard connections.

Beyond the either-or, wired vs. wireless debate, there’s even an electronic FSA WE drivetrain with a bit of both. The truth is all of them work phenomenally well and once you ride one, you’ll almost certainly want one.

The last method of shift actuation is hydraulic. Currently offered only by Rotor, the Uno groupset uses hydraulic fluid and lines to initiate each shift, similar to how hydraulic brakes work except that it’s a fully closed system that shouldn’t require maintenance once installed. This system has yet to gain widespread adoption or OEM specification, but touts very light weight and sealed lines that won’t become contaminated by dirt (and no battery to charge). Maybe we shouldn’t mention that their latest version is about to hit the shelf with a 1x 13-speed road setup.

6. BRAKE TYPES & TRENDS

As previously mentioned, the biggest news in road bike braking is the recent-but-rapid introduction of disc brakes. While traditional road calipers squeeze the rim (i.e. the rim IS the braking surface), discs locate the brake caliper near the wheel’s hub, and clamp on to a disc rotor. Perhaps the biggest impediment to widespread disc adoption was the flip-flopping attitude coming from the UCI, but they finally approved the use of discs full-scale for professional cycling. Discs have become especially popular when used in conjunction with carbon rims, which can have hit-or-miss braking performance when used with rim brakes (especially in wet or dirty riding conditions).

Mechanical or Hydraulic?

Disc brakes come in two main formats: mechanical and hydraulic. Mechanical discs operate much like mechanical shifting – a steel cable runs between the brake lever and caliper. These systems are typically price friendly, but don’t offer the modulation and power of a hydraulic system. They tend to be preferred by people who value mechanical simplicity, and the ability to perform roadside repairs for ultra-distance, middle-of-nowhere competition.

Hydraulic systems cost more, but offer improved modulation – the somewhat subjective band of feel between light braking and full wheel lockup. They are also well sealed from the elements, don’t require the cable replacement of mechanical systems, and provide adjustment as brake pads wear down. However, depending on the type of fluid used, hydraulic systems can require fluid replacement as regularly scheduled maintenance. The hydraulic brakes from SRAM use DOT fluid, which absorb moisture over time and must be replaced more frequently than systems using mineral oil. DOT fluid is preferred, however, by those who ride for extended lengths in sub-zero temperatures, due to its low freezing point. Note that ALL hydraulic brake systems require the use of a specifically-made hydraulic-equipped brake lever (i.e. your old Ultegra shifters in the garage are not forward-compatible, but CAN be used with road-specific mechanical brakes).

There are also some hybrid mechanical/hydraulic systems like the TRP HY/RD, which use a standard cable-driven brake lever that pulls on a self-contained hydraulic caliper. This allows you to upgrade your otherwise mechanical bike into a quasi-hydraulic beast.

Rotor sizes for both mechanical and hydraulic road disc brake systems are 140-160mm. Most modern bikes have settled on 160mm as the standard, or 160mm front, 140mm rear. Larger rotors offer more braking power and potentially better cooling, which is key to keeping their performance from degrading on long descents where you’re more likely to drag the brakes.

What is the Flat Mount standard?

As for attaching those disc calipers to your bike, most newer road bikes use the Flat Mount standard, introduced by Shimano in 2014. It offers a cleaner and lighter installation than post mount or ISO mount (which were really just pulled from mountain bikes, anyway), and this is the future of road disc brake bikes. Note that there are some adapters that allow the use of a post-mount caliper on a flat-mount frame or fork, but NOT the reverse due to geometric limitations. If you’re shopping for lower-budget mechanical brakes that are flat mount compatible, the choices are slim, with the TRP Spyre standing out among its peers.

It’s again worth noting that most road bikes equipped with disc brakes also come with thru-axles, which tend to offer more consistent wheel installation and rotor location than quick release skewers.

What about rim brakes?

Rim brakes do still exist in healthy numbers for road bikes – oddly enough at the unrelated extremes of lower priced bikes or the ultra-performance crowd. While disc bikes have come down in price over time, most of the true budget bikes still feature rim brakes. Also, as of this writing, there still appears to be a small but measurable weight penalty to discs of a couple of hundred grams. Which explains why brands like eeBrakes (now owned by Cane Creek) and Ciamillo are still turning out updated and ever lighter versions of their weight-weenie brakes.

Should I get a disc brake road bike?

Tour Magazine is known for their technical analyses of bike performance, and concluded that disc brakes offer 2-3% shorter stopping distances compared to rim brakes with a traditional rim surface (but did not test any of the new textured alloy braking surfaces from the likes of Mavic or Hed). But that’s in dry weather. Switch to wet weather braking and discs rule supreme. They also found that there is a small aerodynamic penalty associated with some current disc-equipped bikes. All things considered, for our money, we would not buy a rim brake bike in 2019, especially if you consistently ride in wet weather.

7. WHEELS & TIRES

If there’s one part of the modern road bike that has changed most significantly, it’s the wheel and tire department. Save for the fact that they’re still round, there are few parts of a modern high performance wheel system that are the same as one from thirty years ago.

The standard wheel diameter remains at 700c, while wheels for shorter riders have made a slow shift away from 650c to 650b (a.k.a. 27.5″), which is 13mm larger in diameter. Even so, small wheels have fallen in popularity in general, with many brands exclusively offering 700c wheels in all road bike sizes. Canyon is one of the brands that has made the switch to 650b, and has a new women’s line of bikes adopting this wheel size to minimize geometry compromise for smaller cyclists.

Before we get too far ahead of ourselves, let’s look at what has remained relatively constant. For starters, less-expensive wheels are typically made of aluminum, while carbon occupies the higher price points. Aluminum wheels have evolved, however, with nicely machined braking surfaces becoming a standard feature. In addition, there is a new crop of textured aluminum braking surfaces such as Mavic’s Exalith and HED’s Black series – offering unparalleled rim brake performance in wet conditions.

Carbon fiber rims continue to proliferate and hit ever lower price points, though tubular-style wheels (that require glue-on tires or “sew ups”) have fallen in popularity for all but the most serious racers. Once a small niche product, carbon fiber clincher wheels are now quite common, with high-temperature resins and complex construction adding measures of safety. Some early carbon clinchers suffered from heat-related failures under heavy braking conditions, but that concern has largely disappeared when buying rims or wheels from reputable brands. Disc brakes remove brake heat from the rim surface, and have given new life to the category of carbon clincher wheels.

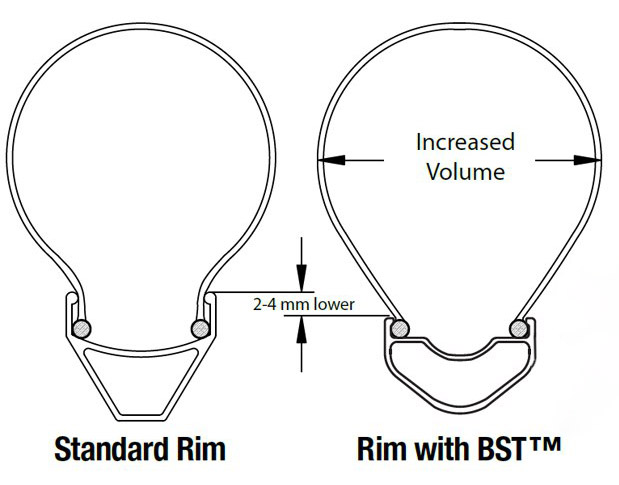

Tubeless-Ready Wheels & Tires

Regardless of rim material or brake type, the hottest trend these days is tubeless tire compatibility. Like your car tires or many mountain bike tires, these are set up without an inner tube inside. While it has taken many years for tubeless tires to find their legs in road cycling, their popularity continues to surge – aided by more wheels that are tubeless-ready from the factory. Some wheels adhere strictly to the Road UST standard, others simply promote a tubeless-friendly design that includes a sealed rim bed with no spoke holes – or a sealing tape to cover the spoke holes. Internal rim designs also feature a channel and “shelf” design to help lock tire beads into place upon inflation, unlike traditional curved rim designs from previous decades.

Regardless of whether or not you use an inner tube, this update to internal rim design slightly changes the procedure of removing or installing a tire. In order to more easily remove or install the tire beads, it’s always best to first push them to the center of the internal rim channel – where the diameter of the wheel is smaller. If one side of the tire bead sits up on the larger-diameter “shelf”, it’s going to be much harder to get that second bead on or off the rim.

Should you go tubeless?

Well, it’s the future, so probably yes. But here’s a few things to consider:

Potential weight savings: Tubeless-ready tires are typically heavier than traditional clincher tires, but most or all of the weight gain is offset by the fact that you lose the inner tube. Often, even with sealant, the system weight is lighter with tubeless.

Improved rolling resistance: Tests have not yet shown a unilateral or unassailable advantage or disadvantage to tubeless tires, but advances in tire construction seem to be headed in that direction. Schwalbe now says their Road Tubeless tires roll faster than their tubulars.

Puncture protection: “Tubeless Ready” means a tire needs tire sealant inside to make it air tight. As in, they’re not “Tubeless Complete”, they’re just easily converted to tubeless. The benefit is that the liquid seals a puncture on-the-fly without you ever needing to remove the tire (or even stop your bike).

A faster, more comfortable ride: For those of you who like to run lower tire pressure, the lack of an inner tube means that you almost can’t pinch flat (and if you impact something hard enough to pinch flat the tire itself – your wheel is likely damaged, too). Lower pressures make for a more compliant, comfortable ride. And, somewhat surprisingly, tests have proven that lower pressures actually roll faster, too.

Low risk investment: Your new bike’s wheels and tires might already be Tubeless Ready (TR), but most new bikes ship with tubes inside. Check the bike brand’s website if the dealer doesn’t know. Bontrager, Hutchinson, Kenda, Schwalbe, Maxxis, Specialized, and more all have TR road tires, and more bikes are shipping with TR wheels, valve stems included in the box. You may only have to add sealant. Don’t like it? Just put a tube back in.

It’s the future: Did we mention that tubeless is the future?

Rim & Tire Widths

The other trend with rims is the fact that they’re getting wider. Rims from fifteen or twenty years ago typically had an internal width of 13 – 15mm. These days, the normal range for road bikes is 17 – 21mm, save some true entry-level bikes that sometimes adhere to older standards. External rim widths have grown from a norm of 18 – 20mm, to the modern range of 22 – 25mm, or more. Both are important numbers, and here’s why:

Internal width is what will inform the tire’s actual shape and width once mounted and inflated. External width is what needs to fit inside your brake calipers, assuming you’re running rim brakes. Modern calipers are mostly capable of fitting the widest road rims on the market, but if you’re adding new wheels to an old bike, check the brake’s specs before buying wide rims.

Wider rims tend to do a few things:

- Better match the rim and tire width, improving aerodynamic performance

- Straighten out the sidewalls of the tire for better cornering stability

- Increase tire volume, allowing for lower tire pressure, leading to improved ride comfort

That last point is an important one, because wide rims can change the effective width of your tire – because labeled tire sizes are still based on old rim widths. In other words, your “23mm” tire might actually inflate to 25 or 26mm when used on a rim with a large internal width. Keep this in mind when buying tires: it’s not the labeled size that counts, but the actual inflated size. Tires that are too large might rub your frame or brake calipers. There is some movement towards defining ideal rim-and-tire width ratios, but they’re nowhere close to being called “standards”.

Almost nobody today is using tires smaller than 23mm. In fact, the generally accepted minimum used by most riders is 25mm, with larger 28-30mm sizes surging in popularity, even among the pros. As previously mentioned, wide rims allow for good aero performance when using wide tires. When you add the ability to run lower pressure for improved comfort and confidence – and it’s easy to see why tires are trending larger. For future-proofing purposes, don’t buy a new road bike that doesn’t have clearance for at least 28mm tires (actual inflated size). As always, it’s better to have and not need, than to need and not have.

8. FREEHUB STANDARDS

A freehub is the modern method for attaching a cluster of gears to your bike, featuring a splined interface and fastening mechanism. The most common freehub standards haven’t changed much, but there are some notes worth explaining. First and foremost, the traditional Shimano HyperGlide (HG) freehub design is still around as the most common road choice, surviving after a brief appearance of a deeper-splined 10-speed-specific freehub that didn’t last.

The biggest change occurred in 2013, when Shimano introduced 11-speed rear shifting, requiring 1.8mm of length to be added to the existing Hyperglide design. New 11-speed wheels are backwards compatible to 9 and 10-speed, but the reverse isn’t always true depending on your hub manufacturer. Read: Your old wheels might not work with the newest drivetrains. But by “old”, we mean anything more than 5 years old. Since then, most hub and wheel manufacturers have built around the 11-speed dimensions.

SRAM offers cassettes using both the Shimano HG 11-speed standard, and their own XD and XDR systems – which allow for a 10-tooth small cog (the HG freehub is limited to an 11-tooth cog). XD was originally introduced for single chainring mountain bike drivetrains, while XDR is slightly longer to match the length of the longer 11-speed Shimano HG freehub (and will offer future compatibility with 12-speed).

Meanwhile, Campagnolo has stayed with their same spline pattern & width for quite some time, and most wheels survived the 11-speed switch with relative ease. Even their latest 12-speed components do not require a new freehub.

Fortunately, most major wheel/hub brands’ hubs have the ability to swap in HG, XDR or Campagnolo freehub bodies. So, if you did decide to swap groups or upgrade in the future, chances are pretty good you’ll only need to swap freehub bodies and not your complete wheel.

9. COCKPIT STANDARDS AND TRENDS

Cockpit? We’re talking about handlebars, stems, and seat posts.

Starting at the front, one growing trend is integration. More and more bikes are hiding the shift and brake lines inside the handlebar and stem, sometimes funneling them directly through the steerer tube and into the frame. The result? You don’t see anything until they reach the brakes and derailleurs, which improves both looks and aerodynamics. The downside is that it often limits your ability to swap parts, and it makes bikes harder to work on, so you’ll probably have to have your local shop do any major adjustments or maintenance.

There are also more integrated GPS and accessory mounts, and even secondary shift buttons for electronic drivetrains – giving you the ability to shift while riding with your hands on the bar tops.

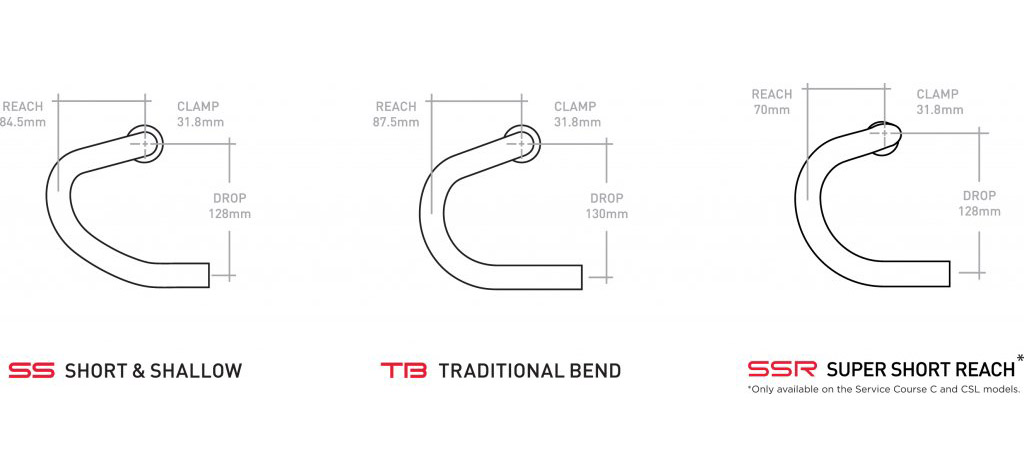

For handlebars, the industry has embraced short and shallow drop styles. There is no exact standard as to what this means, but most feature a drop measurement of around 125-128mm, with a reach of ~70mm. These tend to provide a more realistic drop position that people will actually use, whereas super deep (traditional) drops often lead to riders almost always just using the bar hoods.

We’re also seeing an influx of flared drops of varying degrees, allowing for more control, comfortable hand positions, and less arm/hand interference with the top of the bar when riding in the drops. Wide-flared bars are gaining popularity for the gravel crowd, while more modest degrees of flare are finding their way onto endurance road bikes.

Stems moved from 26.0mm to 31.8mm diameter in the early-mid 2000’s, improving lateral stiffness. Note that both road and mountain bikes had adopted this new shared standard, whereas older mountain bikes used a 25.4mm bar that was NOT cross-compatible with road’s 26.0mm.

In 2011, Deda introduced a new 35mm diameter bar and stem, further improving stiffness. 35mm handlebars own a good bit of the mountain bike market now, but have yet to catch on en masse on the road. The upside is that it is markedly stiffer without adding much weight, so it’s great for powerful riders and sprinters. The downsides are that upgrade options are limited, and, 35mm bars require a new out-front computer and accessory mounts, but K-Edge and others make compatible options. Oh yeah, and they can be super stiff.

Seat posts went through several phases too, but we’ve ended up largely back where we began: aerodynamic or bladed seat posts for the hyper performance crowd, and round seat posts for everyone else. The 27.2 diameter remains popular, especially on endurance bikes due to their more compliant ride than larger 30.9 and 31.6 sizes. Most bikes running Shimano Di2 are now using seatpost batteries stuck inside the bottom of the post. If you’ve never used that groupset, make sure your mechanic shows you how to detach it and where the charging port is on the junction box – sometimes they’re hidden inside the frame… or even the handlebar!

We also went through a several year phase of cuttable seat “masts”, which integrate a post into the frame itself, and rely on a unique saddle rail clamp that can side up and down a few centimeters (sometimes, just millimeters) on the mast for fine adjustments. These proved difficult for travel and fitting in bike boxes, and also created struggles in the event that you want to sell your bike to someone that doesn’t have the same saddle height as you. You can still find a few improved versions of this, such as Trek’s seat mast cap, which affords much more adjustability than early iterations.

10. (MICRO) SUSPENSION

Suspension on a road bike? While you won’t find any heavy duty coil suspension forks for a road bike, there is a growing trend for micro suspension. This isn’t actually new, and we’ve seen quite a few iterations and attempts over the years for special races such as Paris-Roubaix. What’s changing is the popularity, and availability to us mortal consumers that aren’t tackling the Spring Classics.

The simplest of designs rely on engineered flex built into the frame. Cannondale’s SAVE system is a good example, shown above. Sometimes it’s just thin seatstays, or it can expand to incorporate chainstay, top tube and seat tube flex, too.

Others, like Trek’s IsoSpeed Decoupler hides use small mechanical parts, elastomers or pivots that are mostly hidden inside the frame somewhere. While some do add what look more like external shocks like on the Pinarello K10 with electronic micro suspension. As you can expect, adding moving parts also adds more potential failure or fatigue points, witnessed by the recent recall of Specialized’s Future Shock head tube suspension systems. Like mountain bike suspension, these parts need care and feeding to remain in tip-top condition.

11. FORK STANDARDS

Micro-suspension aside, road forks still look like road forks – and can steer you through any fork in the road. The straight 1-1/8″ (1.125 inch) standard still lives on at low-to-mid price points, with tapered designs taking over the high end. Most tapered designs rely on a 1-1/8″ upper bearing with a 1-1/4″ or 1-1/2″ lower bearing – the latter being more common on disc brake-equipped bikes which can most benefit from the added stiffness. Note that there are a few oddballs out there such as Giant’s Overdrive system, which uses a 1-1/4″ upper bearing and requires a special handlebar stem.

Tire clearance is growing in general, after the early and mid-2000’s plagued us with a few road bikes that would only fit 23mm tires. The minimum clearance now stands at 25mm, with many new bikes clearing 28 – 30mm rubber. This is an area where we can confidently say that bigger is better; more clearance will future-proof your purchase. As mentioned in the Wheels & Tires section, we’d be hard pressed to recommend buying a bike that won’t fit 28mm tires in 2019.

We’re also seeing more hidden fender and rack mounts, using threaded inserts molded into the fork and frame dropouts. The bike looks super clean without fenders or racks, but can work as a great commuter or wet weather bike, too.

12. FRAME GEOMETRY

We’ll close with perhaps the most important aspect of any road bike – the frame geometry. In short, much of this was mastered decades ago, through trial and error, smart engineering, and countless miles ridden. By and large, geometry still adheres to the tried-and-true standards.

Of course, there are bikes out there that can suit your specific preferences, and custom bikes if you need something special. Perhaps the biggest change in the last decade has been the introduction of bikes with endurance or “century” geometry. Pioneered by bikes such as the Specialized Roubaix, Trek Pilot series, and Cannondale Synapses of the world, these bikes typically feature a taller head tube, longer wheelbase, and lower bottom bracket than a traditional racing bike. Coupled with larger tire clearance (and often disc brakes), these bikes aim to offer a more realistic handlebar position for the average rider, along with better stability and ride comfort. They aren’t the best choice for your local criterium, but they’re perfect if you value comfort and stability for the long haul. You know, like if you ride your bike because it is fun. And they’re still fast – even the pros are racing on “endurance” bikes for longer, rougher stages.

But what bike should I buy?

As always, our best recommendation when trying to decide which bike is best for you is to go test ride as many as you can. Many bikes share similar specs at a given price point, and each brand has their own marketing jargon for often very similar features. The easiest way to cut through it all is to go ride them and find the one that fits you best.

There you have it! We hope this guide has offered you some value and education, and will steer you towards a smart purchase in 2019 and beyond. Stay tuned for our Gravel/Cyclocross Bike and Mountain Bike Guides!